Editor’s note: State Sen. Phil Baruth has written a biography of U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy that will be released by the University Press of New England in May. This chapter recounts the history of the 1998 race between Leahy and Fred Tuttle.

A note from the author: During the course of writing the book, I found myself researching stories that were tangential to the main narrative line, but which I simply couldn’t resist. Case in point: the surreal story of Leahy’s 1998 race against Tunbridge dairy farmer Fred Tuttle. Given that 2016 is the 20th anniversary of John O’Brien’s classic MAN WITH A PLAN, the film that made Fred a star, it seemed fitting to publish this material in its own right. I thank VTDigger for bringing it to you now.

[I]n mid-1994, Senator Pat Leahy received an unexpected but extremely intriguing phone call. On the other end of the line was Robert Daly, then co-Chairman at Warner Brothers, inviting him out to Los Angeles for a one-day walk-on in the upcoming Batman Forever, starring Jim Carrey and Nicole Kidman. Daly knew of Leahy’s highly public fan-boy interest in the Caped Crusader, and he thought the Senator would get a kick out of spending a day prowling around the set.

It would be an understatement to say that Leahy was delighted, but he was also scrupulous – he insisted on paying his own way to the filming, and noted same to Variety the following year.

Jim Carrey’s career had yet to hit its zenith, and his early box-office appeal made the film a major financial success. Opening weekend set a new all-time record, and only Pixar’s Toy Story earned more in 1995. Leahy’s cameo role, a silent party-goer at the Riddler’s ball, went more or less unremarked upon.

But Leahy had gotten a real kick out of it all – the sun, the shoot, the stars, the premier – and the following year, 1996, he found himself out in California again, at Warner Brothers Burbank studios, filming a similar walk-on for Batman and Robin. It was the fourth (and doomed to be the last) in Warner Brothers original series of Batman films. George Clooney, star of the television drama ER, was slated to replace Val Kilmer as Batman.

Again, Leahy was one of a hundred faces at a wild ball invaded by the film’s arch-villains, Arnold Schwarzeneggar and Uma Thurman, but this time out the camera found Leahy more often. He was grouped standing with some of the principals in the crowd, and while he delivered no lines, he was called upon to react dramatically to the lines of the speakers around him. With his height, his large, smooth head and prominent glasses – and resplendent in a Hollywood tuxedo – Leahy was difficult to miss. If his acting was a bit broad, so was the acting and tone in general. Director Joel Schumacher, according to actor John Glover, would sit on a crane and yell through a megaphone, “Remember, everyone, this is a cartoon!”

Almost from the beginning the film was beset by withering criticism. Schwarzenegger’s one-liners fell horribly flat; on the other hand, critics complained that the codpieces and nipples on the batsuit weren’t quite flat enough. In the end, Batman and Robin (1997) was almost universally acknowledged to be the worst Batman film ever made, no easy distinction to secure. George Clooney apologized profusely for it, and later mused, “I think we might have killed the franchise.” (Over the years, Clooney has made a small cottage industry of these apologies, so much so that by 2014, Vulture could run a fairly long compendium titled, “A Brief History of George Clooney Apologizing for Being a Bad Batman.”)

Still, it’s fair to say that Leahy was smitten by the whole process. He was a fan of Batman films, yes, but now he’d had a real taste of the process by which Hollywood synthesized those dreams – a process at once exacting, artistic, frenetic, surreal. Even the horrible reviews had been an absolute hoot to read.

And of course, with re-election coming up in 1998, Leahy had to believe that the press he’d received for the cameos couldn’t hurt. He’d been in the Senate for nearly twenty-four years, working hard for his state. But it couldn’t hurt to be associated with Gotham’s popular crime-fighting hero, not at all, couldn’t hurt to ease into the election back home in Vermont trailing just a bit of stardust.

And as it turned out, Leahy’s intuition was right about the stardust. He just had it a little backwards when it came to who’d be trailing it.

[A]s a rule, it’s Pat Leahy who has found his way unexpectedly into the cinematic, rather than the stuff of film finding its own unexpected way out. The exception to the rule was John O’Brien’s Man With A Plan (1996).

O’Brien was then an unknown 35-year-old filmmaker, living on a small sheep farm in Tunbridge, Vermont. He’d made just two films previously, neither successful, but Man With A Plan was palpably different from the start. The plot was a disarming combination of political film and existential comic whimsy, an unlikely mash-up of The Candidate and Being There: an elderly dairy farmer, in dire need of health care and an easier way to turn a dollar, challenges a long-time Vermont incumbent for a seat in the US House – and wins by a single vote.

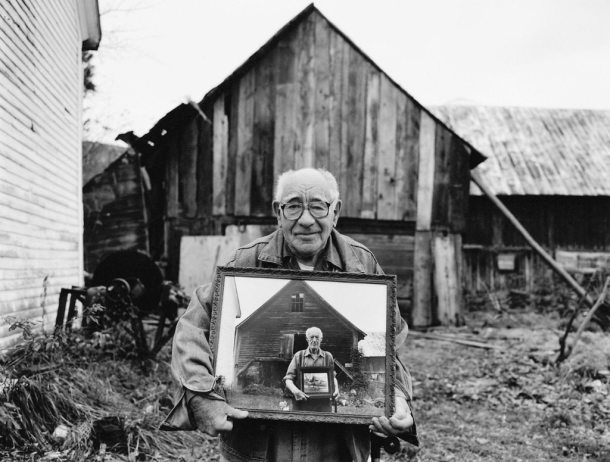

To play the unknown and aging dairy farmer O’Brien recruited his 77-year-old neighbor, an unknown and aging Tunbridge farmer named Frederick Herman Tuttle.

In Fred Tuttle, O’Brien found a star arguably more charismatic than Robert Redford, and arguably less comprehensible than Chauncey Gardiner. At five feet tall and with a Vermont accent a good inch thick, perpetually in bib overalls, thick glasses, and blue feed cap, Fred shuffled through every scene exactly like an arthritic dairy farmer who’d stumbled somehow onto a real live movie shoot, and still couldn’t quite believe his luck. That combination – the hapless acting, and the obvious guileless joy in it all – quickly endeared Tuttle to audiences around the state.

But as much as the film and its star, it was the ingenious roll-out of Man With A Plan that eventually elevated it to cult status. Cryptic “Spread Fred” stickers began to appear with increasing frequency on bumpers around the state. From the start, O’Brien scripted the roll-out very consciously as a faux political campaign, with Fred marching in Labor Day parades and attending the Governor’s press conferences, where he was often asked his take on the issue at hand. It was impossible to say whether Fred was marching in character or not; he’d more or less played himself in Man With A Plan, and he was clearly himself now – loveable and befuddled, but always with an answer to a political question that was both shorter and stranger than the reporter had any right to hope.

That the answers were often completely out of left field mattered not a bit. (Fred on abortion, after a puzzled moment of consideration: “If a woman’s sick, and maybe something happens, then she should be able to get an abortion. But if she went out and got knocked up on purpose, then she shouldn’t be able to.”)

O’Brien was no stranger to Vermont politics – his father had been a State Senator from Orange County, Vermont and a one-time candidate for Governor – and he knew precisely how and when to insert his star into the political calendar as 1997 gave way to 1998 (Fred on the metastasizing Monica Lewinsky scandal: “Oh, let ‘em do what they want.”)

Man With a Plan would go on to sell over 40,000 copies on VCR and DVD, primarily to Vermonters, a huge success in a state with less than 650,000 people. And by September, Fred’s name was popping up spontaneously as a write-in candidate on primary ballots across the state, for offices from President to High Bailiff. The synergy between politics and populist film celebrity was nearly complete.

But not quite.

That sense of complete, vertiginous overlap would come in 1998, when O’Brien’s efforts to leverage Man With A Plan into the potentially lucrative PBS rotation suddenly foundered for lack of funding. PBS had tentatively agreed to take the film on as a so-called “soft feed,” meaning both that individual affiliates could pick and choose when to air it and that O’Brien would have to secure underwriting more or less on his own.

“First Vermont Public Television was going to help us find the money,” O’Brien says with a sigh, “and then they came back and said ‘We can’t find anybody.’ So we went back to Ben and Jerry, who had already turned VPT down once, and this time they eventually put in some money . . . So we said, we have to do something. Somehow we have to come up with free media [to promote the film to the affiliates].”

And since all of the film’s media exposure to date had come through its tongue-in-cheek connection to actual politics, O’Brien began to consider taking the marketing strategy to the next level: running Fred as an actual candidate in an actual race. Given that Fred had run against a longtime Congressman in Man With A Plan, the first thought was to enter Vermont’s upcoming House race against Independent Bernie Sanders.

But even at first blush, O’Brien could tell that the potential storyline lacked voltage. And so he privately ran the idea by the late Peter Freyne, then the state’s must-read political columnist. Freyne’s work was hard-hitting, sometimes brutally so; he was a past-master of narrative, given to assigning telling nicknames and withering storylines to all of Vermont’s powerbrokers. With his specialized nose for all things politically off-kilter, Freyne found the weak link in O’Brien’s prank immediately: for Fred to be the Vermont hero, there had to be not just an opponent but an actual villain – preferably one from out of state.

Freyne’s advice, in fact, was to forget about Bernie Sanders entirely. “Oh no, no, the guy you should really run against,” he told O’Brien, voice dropping and eyebrows rising in the sensational leer that was his trademark, “is this character McMullen.”

Jack McMullen, to be precise, a well-heeled Republican business consultant who had some years back purchased a ski chalet in Vermont, while actively making his fortune in Massachusetts. And a fully fledged character he was. Even for Central Casting, McMullen would have represented a brilliant day’s work: he’d moved to Vermont only a little more than a year before, renting a convenient apartment in Burlington to establish residency, and immediately set his sights on Pat Leahy’s Senate seat. Although he served on the boards of seven different companies, he seemed to know relatively little about the state as a whole. At a glance, McMullen represented precisely the sort of opportunistic, even predatory out-of-state interests O’Brien had spent his short film career lampooning.

But best of all, the would-be GOP nominee for US Senate was a rather slight man who sported an outsized black, Gordon-Liddy-style moustache – like the scoundrel from some silent-era melodrama.

And in fact, the Leahy camp had already softened McMullen up a good bit before O’Brien had even begun to size up the race. Carolyn Dwyer – originally the 1998 Deputy Campaign Manager but later Manager in her own right – puts it in polite terms: “We did what good campaigns do: we did our research, and then identified and labeled [McMullen] before he had a chance to introduce himself. So we had already started talking to members of the press [before Fred entered the primary].”

Not surprisingly it was Luke Albee, then Chief of Staff for Leahy and never one to mince words, who early on gave reporters the most biting formulation: “Call us old-fashioned, but we didn’t think Senator Leahy would be running against a tourist.”

So while there was never any actual coordination during the primary, both the Leahy and Tuttle camps (if O’Brien and Fred and their combined farm animals counted as a camp) were pursuing broadly similar messages, and the combined effect was rapid and powerful. Editorial cartoons began to target McMullen’s brief Vermont residency on a regular basis. University of Vermont political science professor Frank Bryan nailed the growing sentiment in two curt lines, what amounted to a perfect seventeen-syllable Yankee haiku: “McMullen was a walking insult. Who the hell does he think he is?”

The entire set-up was absolute catnip for reporters, and Fred’s celebrity swelled proportionately. McMullen successfully argued that Fred’s candidate petition was actually 23 shy of the requisite 500 signatures; Fred (and O’Brien) responded with an additional wave of 2,300. Over the course of the primary campaign, the spending gap grew more and more ludicrous, and less and less important: McMullen spent $500,000 to Fred’s roughly $200 (one of O’Brien’s best gags was a nickel-a-plate fundraiser for Fred – with four cents the special for seniors).

And O’Brien was smart enough to occasionally leaven the absurdity with lacerating straight talk. Challenged by a television reporter for promoting an unqualified candidate and making a mockery of serious political business, O’Brien responded with the best summary of the campaign to date: “Both candidates are tremendously unqualified. It’s a mockery of a mockery.”

As the primary date loomed, McMullen tried desperately to drag Leahy down into the muck. “I can’t prove it, but I strongly believe Pat Leahy is an active participant in this joke,” he groused to the Washington Post. But Leahy was far too savvy to throw McMullen that particular lifeline and “vehemently” denied the accusation.

The death blow came on the eve of the primary, during a much-anticipated Vermont Public Radio debate. The unusual format called for each candidate to begin by asking the other a series of questions. O’Brien gave those questions considerable thought. “We spent most of the day trying to figure out what Fred could ask Jack – and actually get something out of it. And the questions we came up with went so much better than we expected.”

That would be putting it mildly.

Asked simply to read a short list of Vermont towns, McMullen mangled several by applying an ersatz French pronunciation – thus managing to seem, at a stroke, both elite and new-to-town. And asked point-blank to quantify the working anatomy of a cow, McMullen’s mind seemed finally to shut down altogether under the cumulative weight of the campaign’s absurdity:

In a debate the night before the election, McMullen could name only two of the towns bordering Warren, and had a rather surreal exchange with Fred, who, in his thick Vermont accent, asked, “How many tits a’ Holstein got?”

“What?” McMullen asked.

“Tits!” Fred crowed.

“What?”

“Tits!”

McMullen finally replied, “six.” Those in attendance were not amused. As O’Brien’s mother, Ann, related the story to me, “even city people know that.”

It was a career-ending performance for McMullen – that much was clear within moments of the host’s sign-off. And despite the stout denials of involvement or concern, no one was more gleeful than the Leahyites. The daily skewering of the self-funding Republican – by a protest candidate who hinted broadly that he didn’t actually much want to go to Washington – was a wish come true.

Of course in politics, as in perhaps no other field, you need to be extremely careful what you wish for. Leahy and Pagano and Dwyer listened to the live broadcast of the debate as well, and amid their peals of laughter there were moments of real puzzlement – not so much at the actual questions and answers, but rather at the bizarre convolutions their political world was clearly undergoing.

“You just had this sense,” Dwyer says, looking for words and concepts that still don’t really exist, “that this can’t be happening. You know, in the world we live in – ” She breaks off and takes another stab at it: “This was like a Saturday Night Live skit or something written by Jon Stewart. You just can’t fathom that this is something real.”

But real is as real does. When the results were in on election night, it was amply clear that Fred – for whatever reasons – had honest to God staying power at the ballot box: he defeated McMullen going away, 54% to 44%. (It helped greatly, of course, that Vermont’s was an open primary, in which, as the Washington Post coyly put it, “Democrats can cross over and vote on the Republican ticket, if they’re so moved by a particular candidate – or moved against one.”)

Man With A Plan had become actual on-the-ground political history.

And there was now the authentic crackle of phenomenon in the air. The national and international media – not quite satiated from their feast over the gubernatorial candidacy of wrestler Jesse “The Body” Ventura – began to pepper the Tuttle and Leahy camps with inquiries. The gnawing sense that Leahy himself had had all along – that Fred might actually be a tougher opponent in some ways than the millionaire he dispatched – continued to tinge the hilarity with a moment of occasional unease. As Leahy would later jokingly frame it, “A lot of the places we went to, it was sort of secondary that there was a US Senator there. Everybody wanted to see him.”

And of course, Leahy and his campaign team knew that in a certain very real sense their competition wasn’t a slow-moving dairy farmer who’d only finished the tenth grade by the skin of his teeth. Their real opponent was a very shrewd, thirty-something Harvard graduate with an ability to blend fiction, film and Vermont political reality in ways that were proving staggeringly popular.

Someone a lot like a younger version of Leahy himself.

[P]rivately, Leahy ate the Fred affair up with a spoon – a serving spoon. He loved it. Beyond the belly laughs, he appreciated the irony of O’Brien’s set-up, the deftness of it and yet the lightness of the touch. And the filmmaker’s entrepreneurship. It was pretty brilliant, he told his own team more than once.

But’s it’s also fair to say that Leahy’s feelings on the night of Tuttle’s primary triumph were surprisingly complex. Yes, he was delighted – both for Fred, whom he’d come to like a great deal, and of course for himself and his own chances for re-election.

But more than that, there was something that tasted just faintly like vindication. His last four elections had each been knock-down drag-out affairs. He’d won in 1974, in spite of the media’s open disregard for his chances, by just 4500 votes; after six years serving Vermont in Washington, he’d seen that margin cut nearly in half during the Reagan Revolution of 1980 – and won only after a long, nail-biting recount. In 1986 he’d faced a former five-term Governor, and in 1992 a future four-term Governor, each of whom had given him good reason to think that his current term might be his last.

And during most of these fights, he’d been the lone Democrat in the Congressional delegation, still shouldering his way through the traditional Republican phalanx.

There was a small part of him that couldn’t help but feel that his work in Washington – the headway he’d made for Vermont’s farmers, not the least of it – should have smoothed the path a bit more. But in a way that’s what Fred Tuttle’s nomination represented to Leahy: a path smoothed in advance by voters. Tuttle’s win was a rejection of McMullen’s carpetbagger candidacy, yes, but also a statement by Vermonters of all stripes that if Leahy turned out to be the only viable major-party Senate candidate on the November ballot in 1998, that was more than fine with them.

Voters allowed Fred’s candidacy to succeed because they were in love with Fred Tuttle, and they loved to hate Jack McMullen, but also partially because they didn’t mind the thought of Pat Leahy getting a bye to a fifth term in the United States Senate. (The Burlington Free Press, which would spend the final month of the election alternately cooing over Tuttle and bemoaning the lack of a credible opponent, finally sounded a very similar note: “When a Senator wins a fifth term uncontested, it is in part a signal of a broad public trust. Vermont is confident in Leahy.”)

The trouble was – and here was the final layer of emotion – Leahy felt instinctively that there was real live danger in treating the election as a bye. He’d been burned in enough campaigns to understand that the unexpected would always have its way; there was nothing to say that his own defeat couldn’t or wouldn’t be the climactic end of the still-expanding Fred Tuttle phenomenon.

Overconfidence was the biggest risk. And the whimsical Tuttle/O’Brien campaign would require a particular sort of discipline, because whimsy could only breed carelessness.

And so several days after primary night, Leahy sat down with Pagano, Albee, Dwyer and a few other close aides, and he laid down two principles as gospel. First, Leahy said, we have to maintain the integrity of the election – we don’t want the election, or the democratic process, to become a joke. We’ll have fun with it too, but we need to communicate what we’ve done down in Washington. Then we go to the voters, we ask for their support. Hear their concerns. Go at this professionally from the get-go.

Then Leahy got even more serious in his tone. Second, he said, we need to protect Fred. I know what’s coming when this thing blows up at the national level, I’ve been through it. But Fred hasn’t got the first idea. I don’t want him mocked, or treated disrespectfully, or hurt in any way, by anyone.

Everyone left the room very much on the same page. But Leahy’s campaign team quietly added a third track of their own. Their boss had made it amply clear that Fred was not only off-limits as a target, but persona grata, under the Leahy campaign’s active protection.

But he hadn’t said anything about O’Brien.

Dwyer chooses her words carefully. “On the one hand you have someone who has proven his point and who’s just enjoying the experience and that’s where it starts and ends for [Fred]. And then you have someone behind him who’s now changing the tone and the tenor of the race.”

She gives just the ghost of a smile. “And, you know, it was made quite clear quite quickly that this was a Senate race, and we take it seriously as a Senate race.”

Dwyer uses the passive voice, but of course the active voice – the one who called to put the fear of God into O’Brien – belonged to Luke Albee. O’Brien remembers it vividly: “I told the press, I think [Fred’s] gonna give him a real race and the ideal outcome would be Leahy wins by one vote.” It was meant to be a sly reference to the end of Man With A Plan, in which Fred pulls ahead of his incumbent opponent by that same very narrow margin. But no one in the Leahy camp was laughing, least of all Albee.

“That [talk of a one-vote margin] made them very nervous. And Luke Albee completely let me have it one day over that. I remember having a conversation with Luke not long after we’d won where he was just screaming at me. He’s such a protective and smart guy. And that was when I realized that this is really serious stuff for people in politics, and for me it was just a chance to to be a little tiny shot across the absurdity of politics.”

As the world outside Vermont instantly warmed to Fred, O’Brien was feeling a suddenly chill wind from the state’s political insiders – not just from the Leahyites, but seemingly from all sides.

“For me anyway,” he says with a slightly forlorn chuckle, “it got really lonely really fast. I think the Leahy camp was a bit suspicious and worried that Fred might turn out to be a populist of some sort. Because I didn’t want Fred to just come out and immediately say, ‘Oh, it’s Leahy’s race.’ And the Republicans were all pissed off too, and I got weird anonymous calls saying, like, ‘If we come up with a new candidate, can Fred back out, can we do that?’ Really strange things were going on behind the scenes.”

O’Brien well knew that if Fred announced immediately that he wouldn’t actually oppose Leahy, the force-field that had been building around Tuttle’s campaign would dissipate without accomplishing anything beyond driving a lone carpetbagger from the race. And O’Brien felt that the force field had grown powerful enough that something lasting could be accomplished, without disturbing Leahy’s eventual re-election, if the filmmaker could just puzzle out the what and the how.

But ironically – given the pitch-perfect performance of the primaries – the proper tone continued to elude him. As a satirist, as much as a political operative, O’Brien felt utterly wrongfooted now that his official target was not a GOP comic foil but rather a well-regarded Democratic Senator – a Senator he himself hoped to see returned to Washington. O’Brien found himself second-guessing and then pulling each of his punches, and walking back stunts gone somehow wrong.

Case in point: the Tuttle-Leahy Trail.

It seemed reasonable enough, in O’Brien’s mind. “It probably wasn’t such a great idea but I thought, well, Leahy’s got this enormous war chest. Why don’t we conserve some of the Worcester Highlands and build a trail there called the Tuttle-Leahy Trail with all of Pat’s money?”

Rather than based in the absurd, as were stunts like the nickel-a-plate fundraisers of the primary race, the news conference O’Brien staged to announce what amounted to a campaign finance challenge to Leahy was very real – and, not surprisingly, tense and disappointing as a result. Fred, never one to question O’Brien’s direction (which had led him unexpectedly into a life of blissful celebrity), suddenly grew balky.

“We held the press conference at the Wallace Farm in Waterbury, overlooking this range [to be conserved]. And it completely backfired because, you know, it wasn’t comic at that point. I was trying to do something that would have a sense of timelessness to it. And I think Fred was suspicious about it, because once you got into real policy stuff, he didn’t – he wasn’t comfortable. And Leahy’s people were like, ‘Thank you very much, but we’re going to keep our money.’”

O’Brien seems to look back on that scene from the general election with some real regret – regret that he mishandled the post-primary moment, maybe, but also a deeper regret that he never did puzzle out a way to use the force-field to produce that lasting real-world change, something other than a technicolor political legend.

The Leahy camp’s strategy, on the other hand, produced immediate results on each of its several tracks. Albee’s aggressive push-back had reminded O’Brien of the stakes for progressive political causes; in the process, it had turned O’Brien’s second-guessing into occasional third-guessing. They were in his head, in the way that O’Brien had spent the primary in McMullen’s.

And the Leahy campaign had simultaneously launched a full-scale, take-no-prisoners charm offensive on the very heart of the opposing camp: the Tuttle family farm in Tunbridge.

[I]t was the sort of gesture of respect that McMullen had attempted – once his challenge to Fred’s petitions backfired – but ultimately botched. Dwyer called O’Brien in early October to say that “the Senator and his wife Marcelle would really like to have dinner with Fred and his wife Dottie, but for their convenience the Leahys will travel to their house and bring dinner along, if that sounds good to them.”

It would be an understatement to say the offer sounded good to Fred. The Tuttles were genuinely bowled over by the attention, and on a Tuesday night in mid-October Pat and Marcelle Leahy called on Fred and Dottie Tuttle.

As political summits go, it was perhaps less than august. The Tuttle farm was a down-to-earth place, beautiful but in need of some upkeep, something that O’Brien had gently played upon in Man With a Plan. Dwyer speaks of the evening with real fondness. “Fred was a very humble man, and he and Dottie lived a very humble life. But the Leahys live a pretty modest life themselves – it was a very, very nice evening.”

Modest yes, but also often a life of highly deliberate logistics. Even something as simple as the supper itself was not allowed to leave the extended Leahy circle: a former staffer-turned-caterer baked a suitable chicken pot pie and chocolate chip cookies. The rules of engagement, on the other hand, were deliberately simple – no press, no coverage of any kind, Dwyer and O’Brien present and staffing but eating in the kitchen so that the two couples could talk and socialize.

“It was their dinner,” Dwyer makes clear. “Their conversation was private.” That the two-room seating arrangements would allow Leahy access to Fred without O’Brien’s mediation went unmentioned but understood by both camps.

In large part it actually was two Vermont couples getting to know one another. Marcelle Leahy and Dottie Tuttle took to one another very quickly, and Leahy talked about Fred’s kids, his own kids and grandkids, Vermont – most every subject of small talk except the upcoming election, for which Fred seemed grateful enough.

Yet over the course of the evening, in hints and fits and starts, Fred managed to make it clear that he had absolutely no intention of actually campaigning to unseat Leahy; Dottie made it clear that anyone would have to have taken leave of their senses to vote for her husband (“He doesn’t know one thing about politics . . . . he can’t even get around the house – he expects me to wait on him hand and foot”); and Leahy made it tacitly clear that he planned to continue to promote Fred, if not for the US Senate, then as a Vermont celebrity of the first rank – which was all that mattered to Tuttle in any event.

By the end of two hours it had already become a very comfortable modus vivendi, a partnership of sorts, and simultaneously in the kitchen Dwyer and O’Brien were working out the mechanics of an unprecedented joint campaign swing through the state. O’Brien knew Fred well enough to know that his star was finished with tweaking the powers that be, and so he quickly agreed to Dwyer’s proposal: four joint appearances at schools around the state, press-heavy, promoting Leahy, Fred, civics, voter participation and, as always, Man With A Plan.

It was no Tuttle-Leahy Trail, but the tour was its own sort of statement about what a positive politics could produce.

And so it was that on a chilly morning in late October, a long line of cars wound its way though brilliant red-and-orange foliage to Addison County, Vermont, and converged there on a one-room schoolhouse in Granville, population 298.

In the event, there were more reporters and photographers than children in the schoolroom, but Leahy and Fred – perched in exactly the sort of tiny chairs you might expect in a one-room schoolhouse – made a straight-ahead pitch for civic participation and staying in school. (O’Brien can’t help but finally dissolve into giggles today: “They were pitching for third-graders to stay in school, like there’s this big pressing problem with third-grade drop-outs.”)

It couldn’t have been any more gorgeous, as far as the photographers were concerned, a visual for the ages. As a political event, of course, it bordered on overkill, and sometimes veered spectacularly over the border. Leahy waxed lyrical about the dinner at Fred and Dottie’s and pointed out that Vermont was the only state where Republican and Democrat broke bread together. Fred made it clear he was a died-in-the-wool Leahy man. Leahy praised Fred’s war record. The two bought tickets for the Granville Village School Ice Cream Raffle, and then shared milk and cookies with the kids.

The reporter for USA Today duly bottled the pure Vermont treacle:

“What does it feel like to be a senator?” third-grader Rosely Johnson asked.

“We actually talked about that last night,” Leahy said. “I told Fred he wouldn’t enjoy it.

“You kind of agreed with me, didn’t you?” Leahy asked Tuttle.

“Yeah,” Tuttle said.

This is the Pat and Fred show, a campaign that’s not a contest, starring a Republican candidate who wants his opponent to win.

But at the Granville event, as at the three others, Leahy remained true to his word, telling the school kids that “Fred Tuttle is what’s very special about Vermont.” And their audiences instinctively and consistently responded in two similar but different modes – with clear respect for Leahy, as a sitting US Senator, but with over-the-top adulation for Fred, as a growing Vermont myth come improbably to life.

A Free Press account of the second stop on the tour, a live broadcast from Williston Central School, doesn’t mince words: “Tuttle turned out to be the most popular of the politicians at the school. As he and Leahy strolled down a hallway after the show, students mobbed Tuttle with handshakes and requests for autographs and photographs. They ignored Leahy.”

“At that point, Fred was just a more recognizable celebrity than Leahy,” O’Brien makes clear, and goes on to describe the effect as somewhere between rockstar and SPCA Puppy-Of-The-Month. “So kids would run up to Fred and know him, and women would just spontaneously kiss him . . . that sort of thing. Leahy, you know, he came across as I’ll shake your hand and talk to you, a very nice man, but Fred was like I’ll kiss your wife, I’ll hug your child, I’ll come home with you and eat your beans! I mean, Fred was like the golden retriever of politicians. Fred was in love with that job.”

There was no denying that Fred was the cultural phenomenon, but the partnership lent Leahy an epiphenomenon status beyond the gravitas of long-time US Senator. Each icon actively polished and broadened the reach of the other. The young Tunbridge filmmaker had produced instinctively what we would now recognize as incipient reality programming, and rather than attempt to scuttle the effect, Leahy had instantly understood the political wisdom of amplifying it, bathing in it.

Of course, after twenty-four years in the Senate Leahy wasn’t used to playing second banana, and local reporters well knew it. In desperation to create some hint of tension in the race, the Capitol Bureau Chief for the Free Press finally asked Pagano directly whether Leahy ever tired of “playing straight man to the Tuttle show? Pagano didn’t miss a beat. ‘You want a straight man to represent you in the Senate for six years.’”

And Leahy lived up to his unspoken agreement to promote Fred for everything but the US Senate in another concrete way, as well – he allowed Fred to make the circuit of late-night and afternoon talk shows without requiring equal time, a legal requirement that the Leahy camp could certainly have used if they’d wanted to play hardball.

But Leahy actually liked the thought of Fred on Leno, for the pure ludic kick of it. And it didn’t hurt that Fred would make clear how highly he thought of his Democratic opponent.

Overall O’Brien took it as a very human gesture:

“Leahy was nice in that he immediately signed a waiver saying it’s fine for Fred to be on [Leno] and he doesn’t demand equal time. Of course there was this other [fringe party] candidate who wasn’t going to give in, but I convinced him that if he could be invited to the big Vermont Public Television debate, then he’d back off the Tonight show . . . . But it was nice of Leahy. He was like, ‘Oh no, it’s fine, go out to LA and have a good time.’ So they made all the right calls.”

Thus far, the Leahyites had every reason to be pleased with their truncated re-election campaign. They felt they’d found just the right stance toward the Fred effect, a touch that was gentle yet firm, as the situation demanded. A point of particular pride was that they’d managed to protect their boss and his 79-year-old opponent simultaneously, the toughest part of the marching orders Leahy had given them.

And if anyone thought that Leahy was making too much of the threats possible on the campaign trail, all doubt vanished on October 23rd, when an assassin named James Charles Kopp shot Buffalo obstetrician Bernett Slepian in the back through his kitchen window. It turned out that Slepian’s address had been listed on a radical anti-abortion website known as the Nuremberg Files; within days of his murder, a line had been drawn through his name, indicating that the list as a whole was slated for elimination.

A companion website, Christiangallery, expanded the set of targets:

More recently, Judge Katz, who sentenced Kopp and others, found that he had been listed in the Christiangallery, a web page, which, under a red banner of bright dripping blood denounces “the baby butchers” and their fellow travelers, including Senator Patrick Leahy. The site includes such details as licence plate numbers and names of children and spouses.

Leahy was shocked, but in an odd way he wasn’t completely surprised. “I’ve been on wacko-type lists before,” he growled to reporters. And it was true: he’d received threats throughout his career as a prosecutor, but it was also true that as he’d stepped up his profile as a pro-Choice Senator, he’d sensed in his gut the increase in hostility at the fringes of the national debate. He looked at audiences slightly differently now, with an intermittent, flickering sense that even in Vermont – or maybe especially in largely security-free Vermont – a killer could suddenly loom up out of a crowd.

And Kopp would spend the next several years at large, eluding authorities and keeping many of his purported targets on tenterhooks and continually changing their daily routines.

So while the Leahy connection to the Slepian story was more or less lost in the shuffle before the election, Leahy himself was kept abreast of the details and acted on them, putting in place a security presence on the campaign trail. The Pat and Fred Show continued to produce laughs for the public, but underneath there was now a disturbing new element of threat that had Leahy on a strange sort of emotional roller-coaster.

Before his own Vermont Public Radio debate with Fred – highly anticipated because of the McMullen “six tits” debacle before the same live audience – Leahy took debate practice at the family farm in Middlesex. No one actually played Fred in rehearsal – the thought was that no one could really capture the wildly unpredictable Tunbridge farmer with any hope of accuracy – but true to his first principle about treating the election with respect, Leahy went through his questions and answers diligently.

And no one thought it odd that he also occasionally calmed his nerves between sessions by escaping to the woods behind the house for target practice.

[A]s with most reality programming, the climax of the Leahy-Tuttle Senate race was undeniably anti-climactic. Vermont Public Radio listeners – who’d been rewarded during the Tuttle-McMullen primary debate with multiple game-changing gaffes – could be excused for tuning out midway through the race’s final face-off.

Leahy, as he’d joked earlier on the trail, came with his own blue feed cap stenciled PAT in white (a seasoned pro, he left it on the table rather than wear it for the cameras). Fred answered most questions with lavish praise for his opponent. On roads and transportation funding: “Leahy done a good job on that, and I can’t better it one bit.” On nuclear power and the aging Vermont Yankee reactor in Vernon, Vermont: “Pat Leahy done a wonderful job on that – and it’s perfect.” Leahy kept more or less a straight face during the love-fest, ostentatiously deferring to Fred when a hen farmer called with a head-scratching question about egg coloration: “I’m going to leave it to these two experts – I’m in way over my head on this one!”

Leahy nodded to Fred near the end of the debate, and seemed actually overcome with affection for the Republican nominee. “You’re a good friend,” he told him.

But not everyone was willing to let the race’s last opportunity go so easily. One of the final callers lambasted Leahy for answering too many of the hour’s questions, VPR for hosting a “travesty” of a debate, and O’Brien for putting Fred in the race in the first place. And after Fred defended himself for running against the man he still referred to as “McMillan,” Leahy brought a little heat to the topic himself. He made the case forcefully that the voters had chosen Fred to send a strong message to the “millionaire from Massachusetts,” that a candidate should demonstrate a real commitment to the state before running for higher office. Vermont was not for sale.

“We are not a theme park,” Leahy gruffly insisted, with Tuttle – the dairy-farmer-turned-movie-actor-turned-Senate-candidate-turned-late-night-talk-show-sensation – nodding vigorously behind him.

The other person clearly unwilling to let the moment quietly pass was John O’Brien, whose influence still managed to permeate the debate. The first call from the listening audience was suspiciously O’Brienesque; a man named “Ben” didn’t mention the Tuttle-Leahy Trail by name, but he pushed Leahy politely on his refusal to use campaign funds to conserve mountain land in Vermont.

And as with the McMullen debate, O’Brien had seen an opportunity with the questions Fred would be allowed to pose to Leahy early in the debate, and he’d tried his best to make those questions amusing yet barbed. One such had Fred quizzing Leahy about his relatively high B rating from the National Rifle Association, a group who’d given Fred an F for supporting some limited controls on handguns.

“What can I do,” Fred asked innocently, squinting through his thick black glasses at the notes he’d been given, “to get better grades from the NRA?” Leahy smiled slowly, as much at the tactic as at Fred’s delivery, and gosh-gollied his way through a non-response. “I don’t know the answer to that, but I would never, never flunk you on anything, Fred. I’ll give you an A on anything you want, how’s that?”

O’Brien watched a little resignedly from outside the glass studio, as Leahy took his last few satirical barbs en passante. “Anytime I actually tried to create some friction between them – like I did with McMullen – you know, Leahy’s just too smart to take the bait.”

The ride was over, and O’Brien could feel it. The forcefield he’d sensed so strongly coming out of the primary had powered down substantially – or rather, its energy had now simply been added to Leahy’s own waxing Senatorial aura.

Fred’s closing statement came in his thick, trademark Vermont accent, but the lines were clearly his director’s:

Pat Leahy is a good man. He’s a good Senator, too. Pat Leahy and Jim Jeffords make a good team. They’ve done a lot for Vermont. It’s too bad that they are both lawyers, though. I can’t figure out how to beat Pat Leahy. Orin Hatch likes Pat. Ted Kennedy likes Pat. Even my wife Dottie is going to vote for Pat. Pat Leahy is a Senator who thinks he might like to be a movie star; Fred Tuttle is a movie star who thinks he might like to be a Senator. Maybe for Vermont’s sake we shouldn’t quit.

Embedded in the middle of the paragraph was what amounted to O’Brien’s own concession to Leahy (“I can’t figure out how to beat Pat Leahy”), who had, in a sense, bested O’Brien at his own new and wildly unpredictable game: scripting real life to produce narrative lines with the charm and the persuasive force of fiction.

Still, concession or no, O’Brien was not going to lose what might be his last opportunity to speak a certain ordinarily unspeakable truth about politics, and about Leahy himself.

Pat Leahy is a Senator who thinks he might like to be a movie star. Fred Tuttle is a movie star who thinks he might like to be a Senator.

With that amusing little bit of chiasmus, O’Brien/Tuttle captured a good part of the essence of Patrick Leahy’s rise over Vermont’s post-Watergate political landscape. And it spoke rather slyly to the way that national politics has continued to cross-pollinate with Hollywood and cable entertainment over the last several decades.

What it didn’t do was go far enough.

Leahy would go on to win his fifth term in the Senate with 72% of the vote. Man With A Plan would go on to become the most successful film in Vermont history, selling some 40,000 copies. But not even the shrewd Tunbridge filmmaker could have guessed that in just a little over a decade his one-time political opponent – the straight man to Tuttle’s aging superstar – would somehow become a recurring presence in a film trilogy that would ultimately gross over $2.5 billion dollars worldwide.

Leahy didn’t just think he might like to be a movie star. He knew, and always had.