(“Then Again” is Mark Bushnell’s column on Vermont history.)

[W]e’ve seen this spectacle before: the surrogates of one politician sling mud at their rival, whose own surrogates sling it right back. It’s nothing new.

But it was new in 1826 when two candidates squared off in the most intense campaign Vermont had yet seen. The race for a U.S. Senate seat still ranks among the most rancorous in state history.

The problem was that the two candidates agreed on the basic issues. That left the rival camps to look for differences to highlight, and the campaign quickly devolved into a debate over character.

The incumbent, Horatio Seymour of Middlebury, was an unlikely target for character assassination. Seymour was a recent graduate from Yale when he arrived in town from his home state of Connecticut. He was ambitious and quickly found success as a lawyer.

Though he never took cases outside Addison County, his reputation for integrity spread beyond his home county. After gaining positions as Middlebury’s postmaster and state’s attorney, Seymour won election to the state Executive Council, which served as a sort of second chamber of the Legislature before the state Senate was created.

Seymour assiduously avoided partisan disputes and so developed a reputation as an honest dealer. That reputation helped convince members of the state House of Representatives and the Executive Council in 1820 to elect him to the U.S. Senate, which is how we used to elect senators.

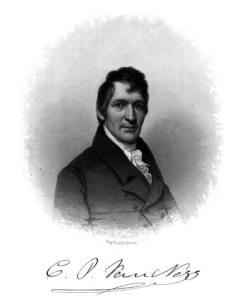

People were less certain about the integrity of Seymour’s challenger. Cornelius Van Ness was handsome and charismatic, a talented politician, and extremely ambitious. His ambition sometimes caused him to change his positions, and offer backroom deals, to further his career.

Van Ness was already a lawyer in his native New York when he moved to St. Albans at the age of 24. Van Ness took on the unpopular job of prosecuting smuggling cases, which put him at odds with many of his neighbors in Franklin County, because the U.S. embargo against trade with British-controlled Canada was killing the local economy. Van Ness was rewarded for his troubles with the post of U.S. district attorney for Vermont at the age of 27, according to historian Kenneth Degree, upon whose research this column is based.

During the War of 1812, Van Ness soon became the collector of customs in Burlington, to which he had moved. In his new position, he managed to quell his distaste for smuggling, turning a blind eye to the importation of goods that were vital to the local economy and the war effort. The customs position earned him appointment to the commission that settled the U.S.-Canadian border after the war.

Van Ness continued to practice law, invested in the newest form of transportation, the steamship, and won election to the state Legislature. But he wanted higher office, preferably in Washington. When a U.S. Senate seat opened in 1820, he lobbied for the appointment, but the House and Council ended up voting overwhelmingly for Seymour.

The next year, however, the Legislature appointed him chief justice of the Vermont Supreme Court. Only two years later, he saw a more appealing position, governor, which he won in 1823. Van Ness served two one-year terms before announcing he wouldn’t seek re-election. He was eyeing the 1826 U.S. Senate election.

Van Ness, recognizing it would be difficult to defeat Seymour, sent emissaries to the senator, saying that if he declined to seek re-election, Van Ness would support him for governor. Van Ness was essentially saying the men could trade offices. Seymour declined.

In terms of policy, little divided the candidates. Both were members of the National Republican party, not to be confused with today’s Republicans, and agreed on the top issue of the day. They supported President John Quincy Adams’ American System, which was widely popular among Vermonters. The system called for the federal government to stimulate economic growth through such means as creating a national bank and investing in road, canal and port construction. The plan was particularly popular in western Vermont, which was benefiting from the recently opened Champlain Canal, which linked the region with New York City.

Seymour’s supporters charged that Van Ness’s ambition would lure him to support the upstart Andrew Jackson, who clearly planned to challenge Adams in the 1828 election. Jackson supported state’s rights and slavery, and bitterly opposed the American System.

Van Ness had given Vermonters good reason to question his commitment to the issues. Earlier in his career, he had supported a state’s right to decide whether it would allow slavery. When it became obvious that most Vermonters disagreed, Van Ness flipped his position. “(T)his wily demagogue, carefully watching, as he has ever done, the course of public sentiment, chopped round and got into its wake,” one contemporary observer noted.

The candidates left the dirty work to supporters who battled in the pages of the era’s highly partisan newspapers. Judah Spooner, editor of the St. Albans Repertory, attacked Van Ness as being self-serving as prosecutor and customs collector. Spooner also reported that Van Ness had met in Burlington with Martin Van Buren, a key operative for Jackson’s new Democratic Party, which was proof to some that Van Ness could not be trusted.

The Northern Sentinel newspaper of Burlington defended Van Ness by identifying the source of the Van Buren report as one of Van Ness’ old enemies and questioning his honesty. The paper did admit that Van Ness met with Van Buren. But the meeting had been by chance, the paper claimed. A change in his travel plans had put Van Buren in Burlington, so he decided to pay a social call on Van Ness, whom had he known since they had grown up together in Kinderhook, New York.

The Sentinel soon attacked Seymour, whose principal flaw was his fear of public speaking. He preferred to do his politicking in private. The Sentinel asked: “On what occasion or question during five sessions in the senate, has he stood up as an able debater, or a powerful advocate of the great interests of agriculture, commerce, and manufacturing?”

The National Standard of Middlebury joined the fray, praising Seymour for exhibiting “a fearlessness, promptitude and decision” that entitled him to re-election.

The tit for tat continued. The Sentinel questioned Seymour’s suitability for office. All this talk about Seymour’s honesty masked the fact that he was actually a “timid, rear-rank sort of man.” The Sentinel claimed that Seymour’s allies only questioned Van Ness’s character to divert attention from the fact he was the more qualified candidate.

The U.S. Senate campaign soon overshadowed races for local state House seats; voters wanted to know whether candidates would back Seymour or Van Ness.

The battle proved fiercest in the Champlain Valley. From its position in comparatively quiet eastern Vermont, Windsor’s Vermont Journal expressed confidence that “closer scrutiny (of the claims) will be instituted when they are brought upon the carpet in Montpelier.”

When the Legislature convened on Friday, Oct. 12, the common wisdom was that Seymour held a roughly 30-vote advantage. The election was scheduled for the 16th. “Van Ness is for delay to work his magic,” commented one witness.

The maneuvering began. Joseph Ingalls of Sheffield, a Van Ness supporter, moved that the Legislature take nominations for county offices on the 16th instead. The change would not only buy Van Ness time, it would allow his aides to swap offices for votes. But Seymour’s backers managed to sidetrack the effort.

The weekend before the vote found both camps lobbying for support. “You can hardly form an idea of the exertions made by V.N. and his friends,” reported a Seymour supporter. “… Hostlers, stage drivers — Barbers and Peddlars (sic) — are singing the song of persecution for him… I wish the Question was decided. For we have great anxiety. And very little pleasure.”

When the vote finally came, Seymour carried the House by 10 votes. Van Ness won in the Council, but only by three votes. Seymour had held his seat.

The Rutland Herald, which hadn’t become embroiled in the battle, pronounced the result fair. Despite the narrow margin, the Herald stated that the representatives who voted for Seymour represented two-thirds of Vermonters.

Van Ness proved a sore loser. Providing no evidence, he claimed that the Adams administration had conspired to defeat him. And the next spring he did what others had feared: he backed Andrew Jackson’s campaign, apparently believing that if Jackson became president, he stood to win a Cabinet position.

His treachery destroyed any chance of winning election again in Vermont. “Van Ness has signed his political death warrant from this state,” observed Daniel Pierce Thompson, a Montpelier lawyer and political activist.

Jackson soundly defeated Adams in 1826. But Vermont had gone to Adams, so Van Ness couldn’t claim to have helped Jackson. A Cabinet post wasn’t happening. To his bitter disappointment, the best position Van Ness could get was ambassador to Spain, and he only got that because Van Buren intervened.

Before departing for Spain, Van Ness exacted revenge. Using his influence with the new administration, he arranged for numerous federally appointed officials in Vermont — postmasters, marshals, district attorneys and the like — to be removed from office. If he wasn’t going to get the office he wanted, neither would his rivals.

(Correction: An earlier version of this column contained an incorrect date.)