David R. Hall has a plan, and he’s done the math.

The wealthy Mormon engineer says he wants to build 20 “sustainable” megalopolises in Vermont, starting with 1 million people in the Upper Valley, where he has bought land around a sacred site of the Latter-day Saints in the tiny town of Sharon.

By his calculation, about 20 million people could fit in Vermont.

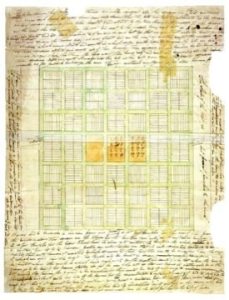

Hall calls the project NewVistas, and while he insists it is not sanctioned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or limited to the church’s members, the religious overtones are hard to ignore. Ground zero for the project is the birthplace of Joseph Smith, the founder of the Mormon church. The NewVistas communities would have a governance structure similar to the Latter-day Saints hierarchy. And the land use design comes from a blueprint for ideal communities devised by Smith, called the “Plat of Zion.”

Hall, a former Mormon bishop, told a regional planning commission in Woodstock last week that he wants to apply Smith’s land use blueprint to the Vermont landscape.

“In my crazy mind, two-thirds of Vermont would be wilderness and one-third would be the farms that are occupied, and you’d have 20 million people in Vermont,” Hall told the commission, hitting his hand on the table to punctuate his remarks. “That’s a crazy idea. But that’s what I can lay out. You’ve got all these people who need a better place. Vermont’s a great place, but we want to do it right. We need more wilderness. What I think we should do through our planning is have land set aside for the wilderness and have other land set aside where the people go.”

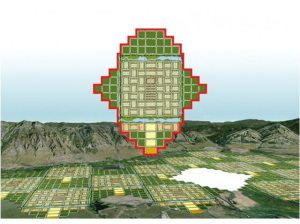

The “Plat of Zion” is made up of a series of interconnected diamonds that are broken up into square units designated for planned development, “hinterlands” for grazing animals and wilderness. NewVistas would superimpose the plat on Vermont’s mountainous topography.

The governance stucture is also highly regimented. The NewVistas communities would be privately held corporations, and members must hand over assets to join.

Hall’s vision isn’t limited to Vermont. He writes in a 23-page description of NewVistas, since removed from his website, that he wants to develop communities in China, Bhutan and India and all of the world’s people can be “housed sustainably in 7,000 NewVistas” that would occupy 1 million square miles, “or 10 percent of the Earth’s arable land.”

While the 69-year-old businessman from Provo, Utah, says his vision for sustainable communities won’t be realized in his lifetime, he sees NewVistas as a “quest,” and he’s getting started now, with the launch of one of the first communities near the Joseph Smith monument. A similar development is underway in Provo.

Hall has purchased 15 properties in Sharon and the neighboring towns of Tunbridge, Royalton and Strafford. The current population of the four towns is roughly 4,500; Hall’s community would add 20,000 residents to the area. Eventually, Hall envisions a megalopolis of 1 million people in the Upper Valley that would be divided into 50 units of 20,000 people occupying 2.88 square miles.

And he has the money to buy more land. Hall told the Valley News he invested $100 million in 25 businesses owned by NewVistas. One of the companies has devised a toilet with medical sensors. Hall says he will spend about $2 million a year in proceeds from the company profits to purchase property over time in Vermont, but in the past seven months he’s already spent about $4 million on the 1,500 acres in Vermont, according to research from local opponents. His goal is to create a contiguous parcel of 5,000 acres.

Many locals are outraged by the potential impact Hall’s proposal could have on the region’s 19th-century villages and bucolic, hilly landscape. Hall met virulent opposition from several residents at a meeting with the Two Rivers-Ottauquechee Regional Planning Commission held Thursday as part of a three-day public relations swing through the Upper Valley orchestrated by Kevin Ellis, a lobbyist with Ellis-Mills.

One of those locals is Gus Speth, a Strafford resident and veteran of the environmental movement who founded the Natural Resources Defense Council.

At the planning commission meeting, Speth said Hall’s first mistake was selecting Strafford, Sharon, Royalton and Tunbridge as the center for his experiment in “social engineering.”

“It’s going to destroy this community,” Speth said. “It’s the biggest existential threat to this area that I can imagine, and that leads to the second mistake. You have landed in a field of warriors, and the people who live here are willing to fight every step of the way to be sure this doesn’t come to fruition.”

Speth suggested that before Hall spends an enormous amount of time and money and ends up with nothing but “a bucket of embarrassment,” he should pull out and put the project somewhere else.

“We are going to fight, and we have the tools to fight, and we are going to get the resources to fight, and in the end it’s not going to happen,” Speth continued. “It’s not going to happen, Mr. Hall. Not here.”

Hall was undeterred by Speth’s impassioned speech and explained in an exasperated tone that he doesn’t intend the Vermont project to happen until several other communities are running and the system “is proven ecologically superior.” He believes that Vermonters “who want to be ecologically correct and advanced would approve of it.”

“I have enough confidence it’s going to happen eventually that I’m willing to spend the money to start consolidating some land now since it will take a generation to do and possibly more,” Hall said. “So I apologize that I have such great confidence in it, but I personally think eventually the people of Vermont will ask for it.”

Speth later said it appeared Hall was making the project sound as though it was way out in the future “in order to lull people into thinking that this is a remote thing that’s not going to happen when you seem to be moving as fast as you can.” He pointed to Hall’s hiring of Ellis, the land purchases and discussions with political leaders as evidence that the project is “going full steam ahead.” Hall has hired six contractors in the region to negotiate land purchases and address legal, accounting and permitting issues.

“You’ll have to trust me on that,” Hall said in reply. “I will need to do all of the things necessary to get people educated and slowly over time get people to like the project. It’s not going to happen overnight.”

The engineer from Provo

David Richard Hall comes from a family of devout Utah Mormons. Growing up, his family lived for a while in Schenectady, New York, where his father, H. Tracy Hall, a physical chemist, worked for General Electric. The family often traveled to Vermont to visit the Joseph Smith Birthplace Memorial in Sharon, and Hall has fond memories of tenting excursions at Camp Joseph. Hall has six siblings.

“I don’t view myself as an outsider,” Hall says.

In 1954, while at GE, Tracy Hall invented a process for creating synthetic diamonds by subjecting carbon to hydraulic pressure and extreme temperatures. In 1960, he was granted a patent for the method. He later founded an industrial diamond manufacturing company, MegaDiamond, which became Novatek International, specializing in diamond drill bits for the oil industry. Tracy Hall died in 2008.

Under David R. Hall’s leadership, Novatek, based in Provo, has continued to develop new technologies and claims to have a portfolio of more than 600 patents. Schlumberger Drilling Group purchased Novatek in September for an undisclosed sum.

While David Hall says his wealth is derived from the fossil fuel industry, he now wants to curb carbon emissions through the development of sustainable communities. A month after he sold Novatek, Hall began quietly purchasing land in the Upper Valley through the NewVistas Foundation, a nonprofit organization formed in March 2015. Nicole Antal, the Sharon library director, discovered the NewVistas purchases as she went through a listing of recent real estate sales and blogged about it for DailyUV.com in March.

Hall is also purchasing homes in the neighborhoods of Spring Hill and Pleasant View, a neighborhood of Provo that is near Brigham Young University, to create a prototype for NewVistas in Utah.

An engineer by trade, Hall likes to describe the details of the NewVistas project. In conversations with the Valley News editorial board, an interview with VTDigger and the planning commission meeting, he talked about greenhouses “more efficient than solar cells” that will be atop the roofs of 24 buildings, each 60,000 square feet, that he plans to build for the NewVistas community in Vermont. He explained that 1,200 acres would be devoted to the community, farmland and “hinterlands” for pasture, and the remaining 3,800 acres for wilderness.

His vision for how the community would function is even more regimented. Every member would be expected to live by strict rules imposed by a for-profit corporation that would be run by a select group of people.

People skills, he admits, are not his forte. Though Hall has served twice as a bishop in the Mormon church — once for a three-year stint overseeing 300 young people between the ages 18 and 30, and for a five-year period providing guidance for the same number of people in his local neighborhood — he said he was uncomfortable with the role. Hall was expected to counsel people in the congregation and said he was “dealing with the soap operas of life” — poverty, divorce, neighborhood disputes, troubled children.

When he described his experience as a 19-year-old missionary in Moonie, Australia, he talked about how frustrating it was to try to persuade men in the oilfields that they shouldn’t be boozing and taking comfort in prostitutes. “Here I am trying to teach them,” Hall recalled. “You learn to be confident. Talk about rejection.”

Hall said the oil rigs were placed 40 acres apart, and the men had to move from one rig to the next and work for short stints. The nature of the work, he believed, was wrecking families. “It wasn’t just an environmental disaster, it was a personal disaster (for the men),” he said. Instead of attempting to counsel them, he came up with an engineering solution: He believed a diamond drill bit that could tap a larger area of oil deposits would enable the men to work in one place from a permanent drill rig for extended periods.

Like his solution for the oil men in Mooney, Hall says the NewVistas project will re-engineer society. New technology and highly organized, planned communities, he believes, will enable people to lower the impact of their carbon footprint on the Earth.

A corporate community

NewVistas is as much of a sustainability experiment as it is a social experiment. The project is a private, for-profit entity that acts more like a corporation than a municipal government, according to documents obtained by VTDigger. Fees that look like taxes would be collected, and the corporation would control land use, transportation and the community environment.

And in stark contrast to the New England tradition of community participation in local school boards, selectboards and town meeting, the NewVistas communities would be “nonpolitical.” In other words, voting isn’t an option.

As Hall put it in a white paper about the project, “a private solution is the only kind of solution available to private persons who want to offer genuine solutions to environmental and social challenges.”

“The kind of hands-on management that is likely to be required to achieve complete sustainability is very hard to achieve in a political system,” Hall wrote. “The whole point is that NewVista is not a political system of any kind and should not be interpreted as doing anything in a political vein, neither tossing aside or enhancing rights or freedoms, because political rights and freedoms are preserved (or not) by broader social systems outside of NewVista, and all of those will remain in place and unaffected by anything done within the NewVista econosystem.”

While you don’t have to be Mormon to join one of Hall’s communities, you do have to be willing to sell your assets and invest all your money in the corporation. The investment will generate an annual return of 12 percent, Hall says.

Instead of owning cars and houses, members of NewVistas would lease housing and rent vehicles as needed. Those who don’t have assets to sell or cash to invest in the pool of community capital can join NewVistas by becoming employees of one of the 1,000 or so businesses created by entrepreneurs in the community, Hall told VTDigger.

There would be no public education, only privately run schools would be allowed in NewVistas. No Mormon temple would be constructed; each community building would have spaces for religious gatherings.

The governance structure is similar to the Mormon church hierarchy, in which a small group controls the activities of thousands of people. There would be six trustees that are part of a self-perpetuating board that would appoint “presidencies and vice presidencies.” Women could serve in leadership positions with their husbands, or solo.

Each of the 24 community structures represents a governance district with its own house captain that is subject to decisions made higher up the leadership food chain.

Hall said in an interview with VTDigger that the governance structure is based on a matrix that allows 30 percent of the members to participate in leadership. The members of the community would be divided into four demographic groups: husbands and wives, single men and single women. All four groups would meet separately by gender. Lesbians, gays and transgender men and women would be allowed to join NewVistas.

Members of the community must make a commitment to shrinking their carbon footprint by 90 percent, Hall said. That means living in a communal environment with no more than 200 square feet of space per person. And limiting personal consumption by eating no red meat or sugar, and drinking no alcohol. Vegetables would be grown in rooftop greenhouses, and animals would graze in the “hinterlands” around the community.

Sacrificing a certain amount of privacy is also a prerequisite for families. The proposed housing plan is based on a townhouse model that is one rod (a biblical unit of measure), or 16.5 feet wide. Each communal living space is a “system” that with the push of a button can be converted into a dining room, living room or bedroom.

The tradeoff? Private bathrooms for each person, access to NBA-size basketball courts and Olympic swimming pools, and food grown on the premises. Manufacturing, commercial operations and community centers would be located adjacent to housing. Greenhouses would be on rooftops, instead of solar panes. Natural gas would be used as fuel, although there is no pipeline currently on the eastern side of the state.

Hall envisions a walkable community with three- to four-story buildings. “It’s better for people to live together, rather than living separately,” he said.

The corporation has a nesting doll structure with three different interrelated entities, including The NewVista Trust, NewVista Property Holdings, LLC, and NewVista Capital, LLC. The trust owns the assets of the company, the holdings group provides goods and services to NewVista businesses, and the capital group has a corporate structure with a CEO, CFO, COO and a culture-education presidency that oversees vocational training and all primary, secondary and higher education.

NewVistas would face a gauntlet of zoning and permitting hurdles, local and state because the proposal mixes industrial and commercial development with residential development. No plans have been submitted to local officials for permitting, and until that happens, Peter Gregory, executive director of the Two Rivers-Ottaquechee Regional Planning Commission, says his group won’t take a stance on the proposal.

Hall describes Vermont’s zoning “as a real curse.”

Despite the appeal of the NewVistas sustainable housing plan, local leaders have already taken umbrage at the way Hall has approached municipal and regional government in Vermont.

Rep. Jim Masland, D-Thetford, who at the planning commission meeting grilled Hall on the land-use and governance structure of the community, said NewVistas appears to be based on the teachings of Joseph Smith, and the community Hall is proposing, isn’t a community at all, but a corporation in which trustees direct what happens, and people who don’t feel comfortable can be asked to leave.

“It’s antithetical to what we do here,” Masland said. “It’s bizarre and fascinating. I can’t imagine how he thinks Vermonters will get with the program.”

Another Democrat in the House, Tim Briglin, is also skeptical.

“I don’t know much about engineering, but I am a student of history,” Briglin said. “For thousands of years, utopian, centrally-planned solutions like Mr. Hall’s NewVista have ended badly for innocent bystanders. I think Vermonters are drawn to humility and repelled by hubris. NewVista is an idea built on a foundation of hubris.”

DISCLOSURE: Kevin Ellis is a board member of the Vermont Journalism Trust. VTDigger is a subsidiary of the trust and maintains editorial independence.

CORRECTION: Hall is purchasing homes in the Spring Hill and Pleasantview neighborhoods of Provo.