The U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division has stepped up enforcement of fair labor laws affecting agricultural operations. In the past two years, several farms have faced heavy fines for “inadvertent violations.”

Vermont farmers face penalties for wage and hour violations most often when they diversify and employ domestic or foreign “seasonal” workers in handling or producing value-added products or sell products from other suppliers. Anything, in fact, that the law regards as “non-agricultural” labor.

Historically, the government has been “more intent on whether [foreign workers] are legal or not,” according to Roger Albee, the former secretary of the Vermont Agency of Agriculture under Gov. Jim Douglas. Now regulators appear to be more focused on fair wages, and Albee says that shift may signal a change in government policy.

State officials held a workshop earlier this month to explain the nuances of the Fair Labor Standards Act. More than 60 farmers attended the four-hour tutorial at the Statehouse.

Highlighting the difficulties many farms face in complying with the Fair Labor Standards Act rules for farmers, Diane Bothfeld, deputy secretary of agriculture, said the goal of the session “is to get better acquainted with the rules of the road, so you don’t get into a tough spot.”

Rep. Will Stevens, I-Shoreham, who hosted the workshop along with the Agency of Agriculture and the Vermont Department of Labor, says there have been a couple of high-profile dairy audits recently, so he hoped the workshop would encourage “conversation.”

But at the start of the mid-morning Q & A session, Stevens suggested “you might want to make your questions hypothetical,” underscoring the anxiety that brought many farmers to the meeting. While asking to remain anonymous, one established small-scale farmer said bluntly that he felt “asking the wrong question could get you targeted.” He added, “If you ask questions in a public way, then you are in the public eye — because they were on the record.”

The officials from the Wage and Hour Division said they want to address farmers’ questions rather than wait until there is a problem.

Christopher Mills, senior investigative adviser for the Northeast regional Wage and Hour Division, began by speaking reassuringly of farmers “inadvertently” breaking the rules, but he declined to elaborate on what prompted past penalties.

His assistant director, Daniel Cronin, soothed fears about being found out of compliance, saying “the first thing [we do] is to plan for compliance and then deal with problems. We’re here to help.”

Kelly Connelley, the investigator assigned to Vermont from the Northeast district office, echoed Cronin by saying, “Well, we are here to help!” And then told the crowd that she goes to inspect for three reasons, “if directed to by my office, if there’s a complaint or … if I happen to go by and decide to take a look.”

When she does stop by, Connelley, a sixth-generation Vermonter, implied she is not looking for problems, but is “genuinely interested in what you guys are doing.”

She said she knows that circumstances may change the way a farm does business — hailstorms or deer can destroy crops and lead to the farmer selling produce from another farm, for example. The problem is that that may lead to losing the agricultural exemption and having to pay workers overtime or remove the exemption for paying the minimum wage.

The collective message was that the feds want to raise farmers’ comfort level so that they are more likely to proactively address questions to the Wage and Hour Division staff rather than wait until they slip up.

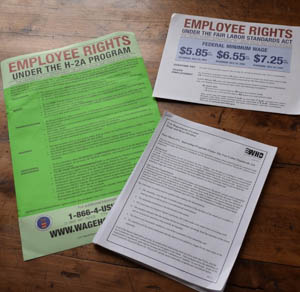

Alyson Eastman, owner of Book-Ends, which specializes in bookkeeping, payroll and advising on employment of seasonal workers under the federal H-2A program, advised the group “not to look at enforcement staff as enemies.”

A changing landscape

Key to the new difficulties farmers face is that today’s diversified farming practices can clash with wage and hour regulations that were enacted 76 years ago with the passage of the Fair Standards and Labor Act in 1938.

Workers engaged in agricultural employment, as defined by federal labor laws, are exempt from overtime and other requirements. But, as more farms sell value-added products or ask workers to complete tasks that are not defined as agricultural, farmers must make adjustments such as revising work assignments in order to keep the agricultural exemption.

The Fair Labor Standards Act rules determine who gets the agricultural exemption for overtime. This federal law also governs hours worked, minimum wage application and disputes, decisions on how to calculate and report wages, job allocation on a farm, how payroll records must be kept in order to avoid penalties, whether interns must be paid or not, child labor law and more.

Mills talked about “the changing nature of agriculture.”

Until about the 1990s, people “pretty much just grew stuff and sold it to people,” he said. Now Vermont farmers produce not just for local and regional but for interstate and even international markets. The result, he said, is that “rules have been a real problem for some people.”

Farmers representing both traditional and new agriculture attended the workshop. There were dairy and maple producers, apple growers, vegetable and fruit producers and farms raising meat animals. Some own hundreds of acres, while others have farms as small as two-and-a-half acres.

There are 7,000 farm operations in Vermont according to the National Agricultural Statistics Service, with 1.22 million acres in use, and the business of farming now often requires workers to do a variety of jobs rather than simply milking or doing fieldwork. Both the need for seasonal workers and the need for them to work a longer season is growing.

This is where a “lack of familiarity with the regulations,” as Mills put it, can trip farmers up. “Read all the sections of the law,” he said. “Don’t just look up ‘dairy farm’ in the index, if that’s what you are.”

Diversified farms, if they need workers to do a variety of jobs, can run afoul of federal labor rules because when work is not defined as “primary or secondary agricultural work,” it can trigger expensive payroll changes like requiring payment of overtime wages for more than 40 hours of work a week.

Critics say this is one of the burdens of a labor standards act that has not been updated to reflect changes in farming. The result, to some, is that it “punishes people in diversified farming.”

Eastman, who pushed for this educational workshop, has watched businesses such as Champlain Orchards change, for example by introducing value-added products and selling apples from other orchards.

“Once you take your apples and bake a pie with them [even] on the farm you lose the agricultural exemption and must pay overtime to those employees that are in the bakery,” she said. ”Also, if you have a farmstand and sell 100 percent of your own product you don’t have to pay overtime, but as soon as you buy and sell your neighbors’ honey in your farmstand you lose the overtime exemption.”

But she added, “Because farms really have so many differences it’s not black and white. I prefer to discuss with each employer their operation and how the FLSA applies to them.”

Eastman has seen changes in work assignments for seasonal workers that can cause problems, partly because the agricultural year is extended and partly because some jobs break FLSA rules.

“Now seasonal migrant workers who, say, come here to pick fruit are doing maple producing, maybe processing poultry — like Thanksgiving turkeys, working on Christmas tree farms or doing field work on a dairy farms,” Eastman says.

Hinting at the head-scratching complexity of applying labor laws, Bill Suhr, owner of Champlain Orchards, said “It was a challenging process to mature as a farmer as I learned federal and state law more thoroughly.”

One result of assigning work so that no one doing “agricultural” labor is also doing what is defined as “non-agricultural” labor — the way to avoid paying overtime — is that workers cannot be trained in a variety of jobs. He lamented that “limiting cross-training lowers morale for workers who want to learn farming.”

Such labor concerns are very much part of today’s farmer’s lot, along with learning how to comply with federal regulations without it costing a lot in money, time and anxiety.