As the saying goes, s–t happens.

It happens a lot in Vermont, as you might expect for a dairy state with an estimated 134,000 cattle, according to the 2011 USDA census.

So let’s do the math, as another saying goes.

Take 134,000 cows all making daily deposits. Then settle on an average weight and apply poop-per-cow estimates, though the figures out there are a bit, well, squishy. (Who knew so many websites calculate cow poop factors. But we digress.)

Suffice to say, a conservative educated guess is that Vermont’s cows produce 10.7 million pounds of cow plop and urine a day. Or if you prefer your manure equivalents in gallons, figure about two million gallons daily. That’s enough manure to fill about three Olympic-sized swimming pools (not that Michael Phelps would ever want to swim in them). Translate that to a yearly total and you get 730 million gallons, give or take a few million.

An Olympian figure, to be sure.

Which is why Les Pike at Keewaydin Farm in Stowe is knee deep in an innovative pilot project with an anaerobic digester system to turn all that brown cow plop from his 170 placid Jerseys into something that smells a lot better and looks a lot greener – and not just environmentally. We’re talking turning cow poop into electricity, bedding for his cows, and heat, all of which will save him greenbacks. And then there’s the smell reduction factor.

“That was a plus being in a resort town,” says Pike, a Stowe native who has been interested in using cow waste to produce electricity and reduce greenhouse gas emissions ever since he graduated from the University of Vermont with classmate Bob Foster.

Foster and several family members went on to operate the 1,800-acre Foster Brothers Farm in Middlebury, one of the first to build an anaerobic digester in 1982. They use it to produce electricity to run their 630-cow farm and produce “Moo-doo” compost, marking the farm as an innovation leader.

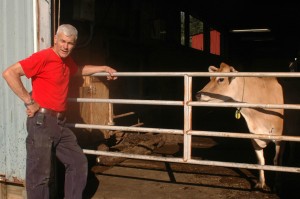

Pike, some three decades and a lot of technology changes later, has finally jumped on the digester bandwagon. Tall, lean and fit, he has close-cropped gray hair and an enthusiasm for things mechanical and technological that belies his 64 years and decades in farming. He runs the 210-acre, neat-as-a-show-garden operation with his wife Claire and two of their three kids. Located a couple miles north of Stowe on busy Route 100, his cows produce around 2,000 gallons of waste a day, stored in a massive round, blue 417,000 gallon tank.

No pun intended, Pike has long thought that’s a waste.

A long quonset-hut building with a translucent ag-bag roof holds his solution: It’s a digester that looks like a bizarre, giant 60-foot-long intestine, thanks to its rough foam insulated covering. Built by a Burlington startup firm called Avatar Energy, the novel design is “scalable” for smaller farms, using fiberglass tube-tanks that are less expensive than the large in-ground concrete-tank digesters used at most of the anaerobic digesters in the state, which typically handle waste from 1,000 cows or so. That makes it also a lot less expensive than the large systems, which can cost several million dollars.

So far, though, it’s not doing what it’s supposed to. Built in 2010, it only recently started producing more power than it used as Avatar refines the complex system and technology. That hasn’t dimmed his interest, though he says, “I’ll be excited when it’s working.”

On a concrete pad Pike shows off the odorless brown material that is extruded at one end of the digesting tube. Made from the undigested solids that pass through his cows and purified of pathogens in the process, it looks and feels like peat moss. He uses it for bedding, saving the several thousand dollars it costs for a load of wood shavings – when he can even get them.

The methane produced runs a 20-kilowatt generator tucked in a metal housing about the size of a pickup truck bed. When it is fully operable, it will generate enough to power the four houses and farm operation on his property, saving him around $750 in utility costs a month. The heat from the generator flows back into the digester to keep the microbes happy. The liquid wastes that emerge are concentrated fertilizer, which has a low odor.

All that adds up – in theory anyway – to savings that “are significant numbers,” Pike says.

Anaerobic (that is, without oxygen) digestion is a natural process that has been harnessed since “Babylonian times,” says Dan Scruton, the Vermont Agriculture Agency’s dairy and energy chief.

In 2010, 162 anaerobic digesters generated 453 million kWh of energy in the United States in agricultural operations, enough to power 25,000 average-sized homes, according to the non-partisan Center for Climate and Energy Solutions in Alexandria, Va. But Europe is way ahead of the U.S. in using digesters to convert agricultural, industrial and municipal wastes into biogases to generate electricity: Germany leads with 6,800 large-scale anaerobic digesters, according to the center. It estimates China has eight million.

For Vermont’s dairy industry, facing pollution issues and squeezed by rising costs, this natural process holds a lot of promise.

“It’s not going to be the silver bullet but it’s one of the things that is really going to help,” says Thomas Vogelmann, dean of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at the University of Vermont. UVM and other partners such as the Vermont Department of Agriculture have put Vermont in the forefront of research into the science of turning animal waste into gaseous gold in the form of methane.

Vogelmann explains that while anaerobic digestion is a well-known natural process, managing it remains as much art as science. Dr. André-Denis Wright, who chairs the animal science department at UVM, is working to change that by studying “the microbial ecology” of cow wastes, Vogelmann explains. His research is sequencing the microbes’ DNA and nailing down optimal temperatures to make digesters function properly in an effort to better understand the variables and standardize the process.

Calling Wright “one of the world’s foremost authorities,” Vogelmann says “there’s a real role here for science to start picking these things apart.”

Scruton, who has spent much of his 27 years at the agency working to promote and find funding for digesters, is optimistic that technology and equipment is reaching a “critical mass.” Of the 13 farm digesters in the state now, 10 are enrolled under the Central Vermont Public Service “Cow Power” program, with two additional farms expected to be added by the end of the year and a total of 18 by the end of 2013, according to CVPS. The units now on line produce around three megawatts of power but the Legislature last session removed caps that restricted new farms from joining in power production using methane.

“About half the manure in the state will eventually go through a digester and that’s about 15 megawatts of power, by 2025,” he suggests.

Pike would love to see that prognostication come true, starting with his own farm.

“If it works, it’s a win-win for everyone,” he says.