When Gov. Phil Scott announced that state workers would need to return to offices at least three days per week starting Dec. 1, the state employees’ union warned the initiative could cause a mass exodus of top staff.

So far, that doesn’t appear to be the case.

Comparing mid-September to mid-December of 2025 to the same period in 2024, retirements are up slightly from 66 to 76, according to data from the Vermont Department of Human Resources. Resignations, on the other hand, have fallen from 205 to 185, a drop of nearly 10% compared to last year.

Sarah Clark, Vermont’s secretary of administration, said in an interview earlier this month that the number of applicants for state jobs has actually risen.

“When you look out at what’s happening both in the federal government and the private sector, I think state government is a very attractive employer,” Clark said, crediting in part the state’s health and pension benefits.

The Vermont state government and its employees’ union have been facing off since Gov. Phil Scott announced this summer that employees would need to return to work in-person at least three days a week. Like many employers around the country, Vermont’s government is navigating the challenge of trying to bring its workforce back into the office more regularly following the normalization of remote work during the Covid-19 pandemic.

As for how the first month of the three-day office mandate is going, Clark described it as relatively smooth, though navigating childcare and long commutes are top issues state employees have reported.

“This is a big change for our workforce, and I’m empathetic to their concerns and needs,” she said. “But (I’m) also excited about the opportunity that it presents for us supporting Vermonters and also working collectively together.”

Despite the administration’s optimism, the Vermont State Employees’ Association — the union representing state workers — is continuing to pursue legal challenges to the mandate.

The administration “didn’t talk to employees. They just threw this out there, and said, ‘This is the way it is,’” Steve Howard, the union’s executive director, said. “We don’t agree with that. We think they have an obligation to bargain with us.”

In late November, the state employees’ union took the Scott administration to court, hoping a judge would deny or delay the return to office mandate. The judge ultimately did not issue an injunction, finding that state employees had sufficient relief available to them through the state’s exemption process, through which employees can make their case for working remotely more than two days per week. But the union has continued its legal challenges, with a Vermont Labor Relation Board hearing expected in February, according to Howard.

Howard said employees have received “contradictory guidance” from managers about when to apply for exemptions and what might qualify a person for an exemption, and some supervisors “still don’t know what to tell people” about how to navigate the mandate.

As of mid-December, the Scott administration had received about 500 requests for exceptions to the in-office policy. About 40 had been approved, according to Clark, and the rest remained outstanding, with employees allowed to work their previous schedules while their requests are processed.

State leaders have said they are reviewing all employee requests for more remote work flexibility on a case-by-base basis. It’s unclear if the approved requests have any similarities. While state-issued guidance has listed very limited circumstances when exemptions may be warranted, officials have said exceptions are not limited to those reasons. Any employee who believes they have a “compelling reason” for an exception can make their case, according to state guidance.

Vermont’s flexible working arrangements law also allows employees to request changes to their working arrangements, such as remote work flexibility. Employers must consider an employee’s request and whether it “could be granted in a manner that is not inconsistent with its business operations or its legal or contractual obligations.”

Half to two-thirds of state employees had already been working in person more than three days per week and thus their work was not impacted by the hybrid mandate, Clark said.

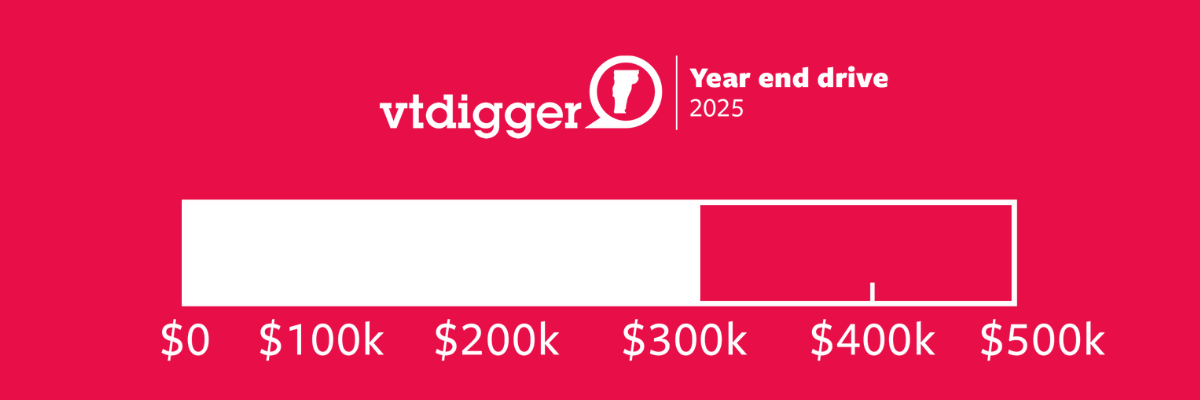

In a tight budget year, the added cost of returning to offices has drawn criticism. The state is leasing new office space in Waterbury to accommodate workers, paying $430,000 in the first year and $2.3 million by the end of a five year lease.

The new offices also require one-time costs to prepare the sites to be occupied by state workers, which total $385,000, according to Clark.

While data doesn’t show a mass exodus of state employees, some have reported resigning as a result of the return to office.

Matthew Grimo, a paralegal with the Vermont Agency of Transportation, said he had been commuting two days per week from Burlington to Barre. An extra day of the roughly 50-minute commute wasn’t a financial burden he could accept. Grimo submitted his resignation last week.

“I love my team, I love working with my team,” he said, “One hundred percent I wouldn’t have considered this if the return to office had not cropped up.”

Grimo said he submitted a request to be exempted from the three-day requirement in November and had continued commuting two days per week since — the number of days he’d been told to commute when he was hired in 2024. But he had yet to hear back from the state, Grimo said, and felt he had to assume his exemption wouldn’t be approved and decided to resign accordingly.

“The state, the administration was incredibly unclear, and to this day, is still incredibly unclear with exactly what they expect and what they will allow with employees,” he said.

In his new job, Grimo will actually need to commute more often, but the drive will be much shorter.

“It’s five minutes from my house versus an hour,” he said, “which makes all the difference to me.”