America had been dragged into the world’s war and daily life had changed. Perhaps at no time was that more obvious than around Christmas.

“New Englanders will observe their second Christmas of World War II tomorrow under far more stringent conditions than prevailed at Yuletide last year,” stated an Associated Press article on Christmas Eve 1942. “Then — only a few weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor — the situation was much the same as in peacetime. U-boats hadn’t appeared off the coast at that time. Fuel was plentiful. Lights were bright.”

Now the lights of Christmas had literally been dimmed as a precaution against enemy bombers, and little seemed the same.

Despite the hardships of war, some already could envision a brighter future. Kirke L. Simpson, a Pulitzer-Prize-winning correspondent for the Associated Press, saw more reason for optimism that year than in 1941, when Christmas had been celebrated in the wake of Pearl Harbor. This second Christmas of America at war, he wrote, held “promise that the coming twelve months will see the last lingering doubt of ultimate victory for the United Nations over the Axis erased.”

Headlines in Vermont papers might have left readers with mixed feelings. War stories carried datelines from London, Stockholm, Moscow, Allied Headquarters in Australia and Allied Headquarters in North Africa; this was truly a global war. But that December the news was mostly good.

“On this anniversary of Pearl Harbor the Axis was beginning to see the size of the bill it must pay,” began an article that ran in the Burlington Free Press on Dec. 7.

Newspapers on Friday, Dec. 18 brought further welcome news: the German army in North Africa was on the run. “British Hurrying Rommel’s Retreat While Mopping Up Pocketed Forces,” a Barre Daily Times headline read.

But Vermonters seemed more focused on what was happening locally: Long lines of cars had started forming at gas stations that morning as reports emerged that the federal government might be about to shut off gas supplies for all non-commercial vehicles.

“Rutland car owners wanted full gasoline tanks for whatever emergency might be coming,” the Herald reported. For a while a false rumor circulated and was repeated on a local radio station that the ban had been lifted, but the rush to the pumps continued unabated. By afternoon, the local ration board was calling gas stations to announce the new rules. Stations that had received word sat virtually deserted, while nearby stations that hadn’t officially been notified continued to sell gas to long lines of cars.

After what the Associated Press called “the most motorless week end the eastern seaboard has known since the horse and buggy days,” the ban was lifted on Monday, though gasoline for non-commercial use was limited to three gallons per purchase.

Despite the shortages and calls for conservation, local businesses tried to ensure Vermonters didn’t conserve too much. These businesses wanted to stay in business. An ad for Pico ski area announced that the area had good conditions and that the lift would run daily, though the rope tow had been closed during the gas emergency. The ski area asked skiers to carpool so that “this healthful out-of-door activity may be enjoyed by as many as possible.”

The Barre Merchants Bureau portrayed war as a buying opportunity, suggesting a little shopping was a civic virtue. “As far as wartime demands permit, let us ‘keep the home fires burning’ by observing Christmas in our usual American way!” a merchants bureau ad declared. In case anyone was unclear what “our usual American way” meant, the ad urged people to “Shop Early in Barre.”

The Central Vermont Public Service Corporation offered electric coffeemakers, marketing them as “a practical wartime gift.” With coffee in short supply, these coffeemakers required less coffee to brew a tasty cup.

An ad for an automotive part store offered readers tips for saving gasoline. “Don’t Let Gas-Wasters Sabotage Your Motor Car” read its headline. The ad offered nine tips, all of which involved buying new car parts, including a new motor, battery or spark plugs. It even suggested buying a locking gas cap to keep “gas bandits” from syphoning gasoline.

In addition to gas, Seguin’s service stations in Montpelier and Burlington were selling an “Army Bild-A-Set.” The 95-cent set included toy soldiers, motorcycles, jeeps, tanks and planes. “Take command of ‘little generals,’ ” the ad stated. “ ‘Lead your company into battle or put them through maneuvers.”

Burlington’s newspapers ran regular articles urging readers to donate toys, clothing and sports equipment to the Good Fellows Club’s charity drive. “The 300 families upon which Good Fellows will heap good fortunate and cheer on Christmas Day if the present flow of donations keeps up, are, for the most part, destitute of even the commonest comforts,” according to a Daily News article. “The ‘neediest cases’ reported by the six participating agencies are no mere product of the imagination; they are typical of the need existing in this community.”

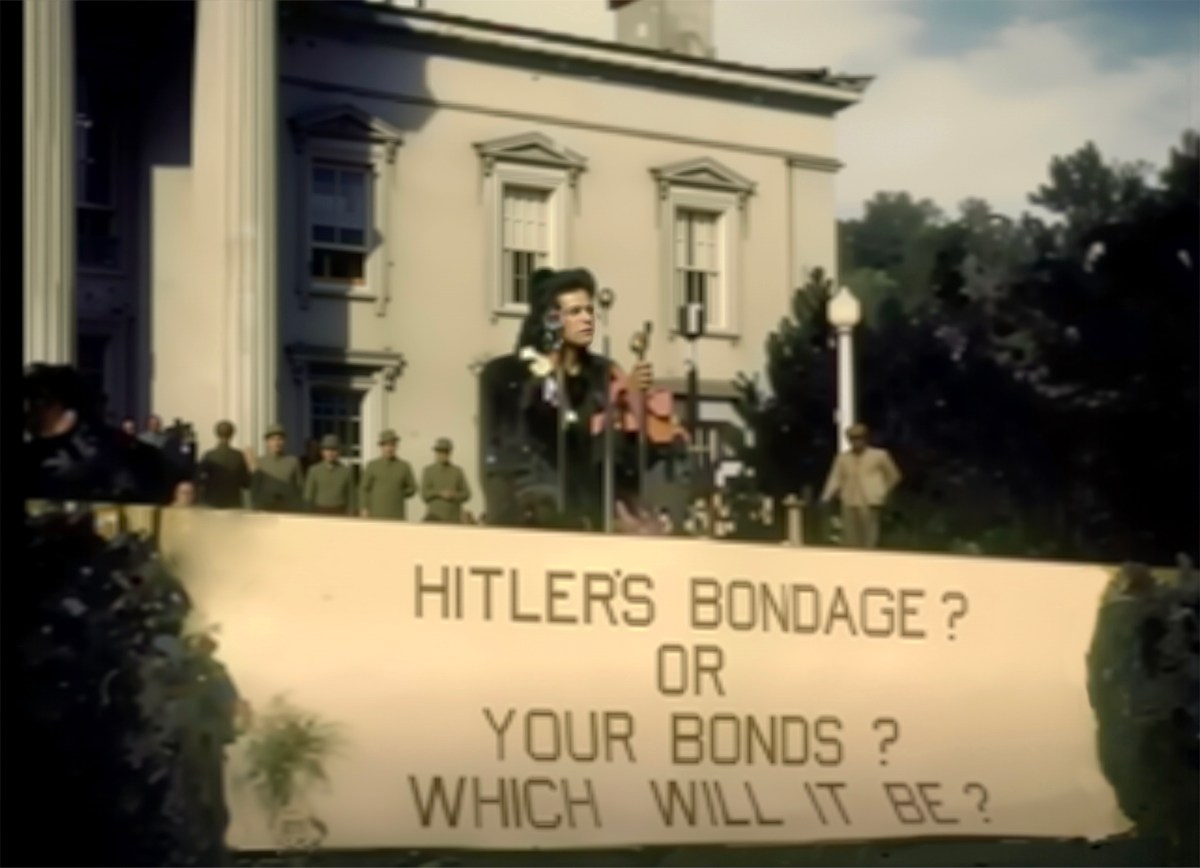

The Rutland Savings Bank suggested people contribute to the war effort by making an unusual holiday purchase: “You send Hitler or Hirohito a bomb with your compliments when you buy a War Bond. A last-minute suggestion for a Christmas present. A Victory Bond!”

The Rutland Herald told of two young girls from a disadvantaged family in that city who assumed that “St. Nicholas couldn’t possibly ‘make it’ this year to their one-room home.” The girls still wanted to decorate their home, so they had “cheerfully wrapped empty boxes, labeled them, and placed them under the Christmas tree.”

“Santa,” however, did arrive, the newspaper reported, having been directed there by the local social services committee. The girls received dolls, modeling clay, crayons, mittens, bright red socks and a variety of toys, and the family was treated to a “real Christmas dinner, chicken and all the fixin’s.”

Even a world war couldn’t diminish the importance of the holiday, the Herald declared in its Christmas Day editorial.

“It seems to us that today means more, to more people, in more places than any other Christmas we can remember,” the Herald wrote. “This year is different. Shopping has been more difficult because there were fewer of the things we wanted to buy. Homes are a little chilly too due to fuel oil scarcity. Even the familiar colored lights in the yard are fewer this year because of dimout regulations.”

The Rutland Herald wrote that the local men in the military “are thinking of Christmas back home; of Vermont’s hills and mountains and how green the trees are against the whiteness of the snow.”

The missing family members, the frightening news from the front and the shortages hadn’t dimmed the holiday’s spirit, the editorial declared.

“War has not stripped Christmas of its meaning; rather has it brought out its true significance. Some of the tinsel and glitter are gone, but its promise is clearer and more unmistakable than ever. It seems to us that this year when people say ‘Merry Christmas,’ they mean it, as they have never meant it before. Merry Christmas!”