Nobel Prize winning author Sinclair Lewis sequestered himself on his Vermont farm during the summer of 1935 and hammered away on his latest novel. He was in a hurry, fearing that real-world events might overtake his narrative.

For his plot, Lewis drew from national and international headlines of the day, but he made the main character a Vermont newspaper editor and set most of the story among the green valleys of his adopted home. For 12 hours a day, seven days a week, Lewis plotted his story and then tapped it out on his portable typewriter, before making copious handwritten revisions to the text. He finished the 498-page manuscript on August 13. It told a story sure to grab the public’s attention.

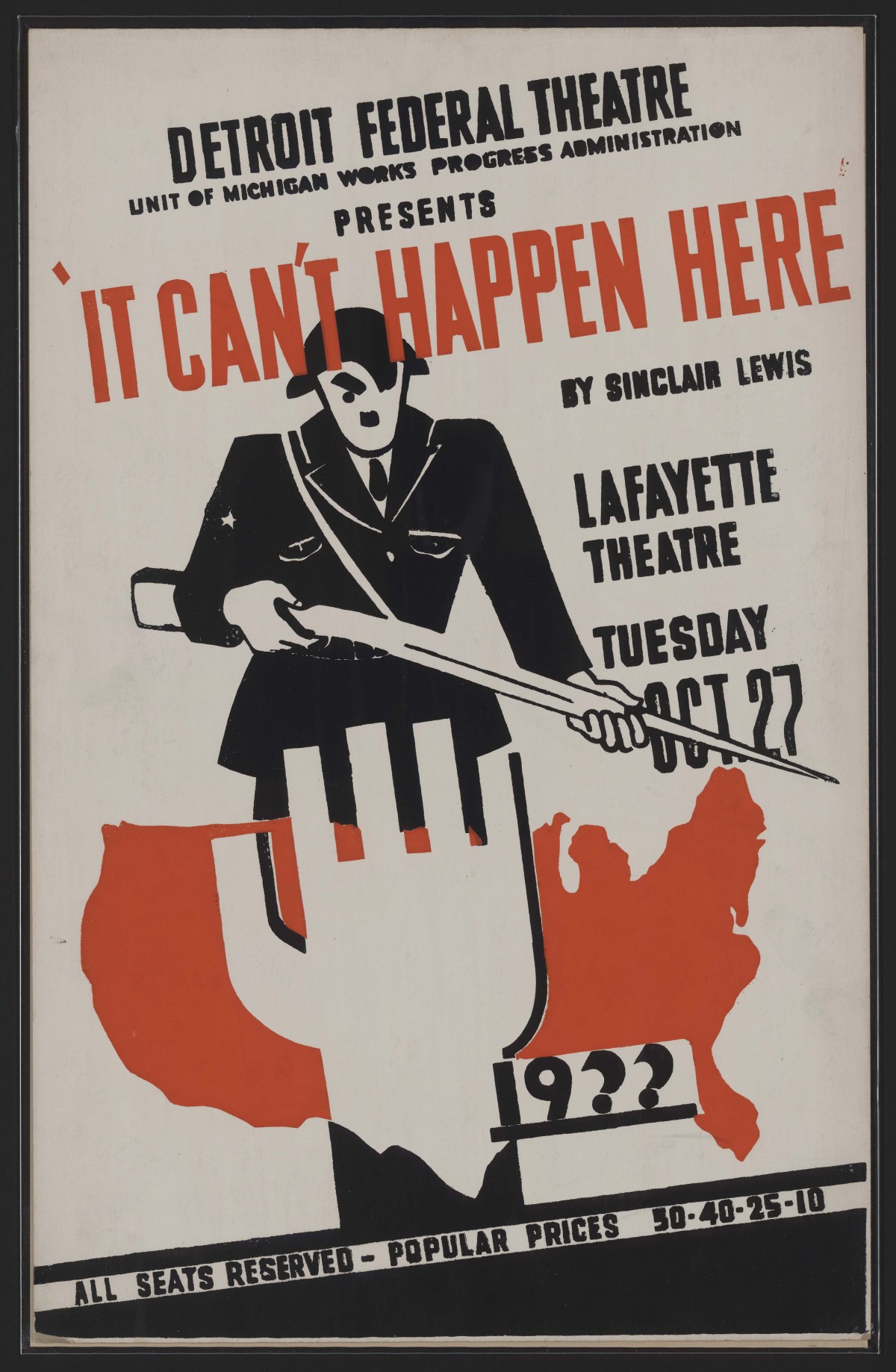

The resulting book, “It Can’t Happen Here,” was an instant bestseller. It tells the dystopian story of a populist American politician, Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip, who stokes people’s fears and preys on their patriotism, promising sweeping reforms to return the country to its original values. Windrip defeats Franklin Roosevelt in the Democratic primary and is then elected president. Once in power, Windrip leads a fascist takeover of the United States. He declares martial law to neutralize Congress, which had refused to pass his legislation, and disempower the Supreme Court, which could have blocked his decrees. Windrip’s violent paramilitary force, the Minute Men, suppresses opposition. Windrip seizes control of the media in a way that makes it appear the country still has a free press; he censors some journalists while co-opting others to spread his propaganda.

In 1935, Lewis, like many Americans, was alarmed by the rise of fascism in Europe, led by Adolf Hitler in Germany and Benito Mussolini in Italy. Lewis was well informed about the situation, hearing firsthand details from his wife, famed journalist Dorothy Thompson, who had been a correspondent in Germany. Thompson had interviewed Hitler when he was still aspiring to power and wrote a dismissive profile. Hitler didn’t forget the slight. After he became German chancellor, he had Thompson expelled from the country.

American politics had its share of demagogues during the 1930s. Among the most prominent was Louisiana Gov. Huey Long, who promised to obliterate privilege and wealth in order to make “every man a king.” At the same time, Long ran Louisiana with an iron fist while facing credible claims that he committed bribery, election fraud, and voter intimidation; put loyalists into state jobs, profited from ties to oil companies doing business with his state, and even tried to get his bodyguard to kill a political rival. As Lewis wrote his novel, Long was eyeing challenging Roosevelt in the Democratic primary.

It may be hard now to imagine Roosevelt as politically vulnerable—he would ultimately be re-elected president three times—but in 1935 he was in his first term, America was in the depths of the Great Depression, and his wide-ranging programs had yet to alleviate American suffering.

Vermont served as a sanctuary for Lewis, who yearned to return whenever he was gone too long.

On a property-buying expedition in Vermont in 1928, Lewis and Thompson visited their New York City landlord’s 300-acre property in Barnard. They were so struck by the stone walls, mixed woodlands and distant view of Mount Ascutney that they offered $10,000 on the spot for the property, which was worth about $3,000, if it were farmed. Their landlord jumped at the offer, leaving the next day for Florida, where he planned to retire.

The Barnard property had two farmhouses; Thompson and Lewis called it Twin Farms and made it their warm-weather base. They would live in the smaller house and renovate the larger as a guesthouse. The couple hired a large staff of locals to maintain the houses and grounds. Thompson invited employees to bring their children to work so her son would have playmates. Seeking a quiet spot away from the children, Lewis shifted his office to the guesthouse.

Lewis wasn’t a recluse, though. When he wasn’t working, he would often socialize with Vermonters, particularly writers and journalists, and became conversant in the state’s history. Speaking to the Rotary Club of Rutland, he declared his love for his adopted state: “Vermont is the first place I have seen where I really wanted to have my home—a place to spend the rest of my life.”

Lewis sets the opening scene of “It Can’t Happen Here” at a Rotary Club meeting in the fictional Vermont city of Fort Beulah, which he describes as a “comfortable village of old red brick, old granite workshops, and houses of white clapboards or gray shingles, with a few smug little modern bungalows, yellow or seal brown.” Lewis supposedly modelled Fort Beulah after Rutland, though he makes Fort Beulah’s main product granite in place of Rutland’s marble.

The speakers at the meeting are a cantankerous retired general and a conservative female activist. The general says he doesn’t “altogether admire everything Germany and Italy have done,” but urges the United States to mimic their belligerence toward other countries: “We’ve got strength and will, and for whomever has those divine qualities it’s not only a right, it’s a duty, to use ’em!”

Meanwhile, the conservative activist urges a return to what she considers traditional American values. She is best known for opposing the right of women to vote and calling for women to remain at home and have as many babies as possible.

Discussing the meeting afterward, the book’s protagonist, Doremus Jessup, the 60-year-old editor of the city’s newspaper, is dismayed to hear a local businessman, banker, school superintendent, and others agreeing with much of what the speakers said. The businessman even praises Hitler. Jessup is incredulous: “Cure the evils of Democracy by the evils of Fascism!”

While the others seem to relish the prospect of a Windrip presidency, Jessup worries what he would do once in office. “Wait till Buzz takes charge of us,” he says. “A real Fascist dictatorship!”

When Windrip wins, Jessup is forced into the role of opposition, writing editorials against the administration. Things spiral out of control. The government seizes Jessup’s newspaper. When he is caught publishing anti-government pamphlets for a resistance movement called the New Underground, he is thrown into a concentration camp, where he is tortured by the Minute Men. Jessup escapes and flees to Canada. By the end of the book, he has slipped back into the United States, under the alias William Barton Dobbs, to spy for the New Underground.

Immediately after the book was published, people tried to figure out who was the inspiration for Jessup. Many believed it was Howard Hindley, the longtime editor of the Rutland Herald and a friend of Lewis. It was an entertaining theory, but Vermont author Charles Crane, in his 1937 book “Let Me Show You Vermont,” wrote: “It’s not so, as both Lewis and Hindley declare.”

Crane quoted Hindley as saying, “I’m not at all like Doremus Jessup. I’m…not given to philosophical remarks such as are put into Jessup’s mouth by the author, and certainly I wouldn’t have the guts to go through what Jessup did.”

Most scholars believe that Jessup isn’t modelled after a real-life individual, but instead represents upper middle class, small-town, political moderates who were struggling to figure out how to confront the rise of Fascism. Lewis also seems to speak through the character, expressing his own concerns about current events and fears about the future.

Lewis’ book mentioned a real-life, one-time Vermont resident who, although little remembered today, played a role in the promotion of fascism in America.

At one point in the story, Windrip lists people who have inspired him and mentions William Dudley Pelley. During the 1930s, Pelley was a leading American fascist. But before his life took that dark turn, he was a Vermont newspaperman. Born in Massachusetts in 1890, Pelley moved to Vermont in his mid-20s to work for the Bennington Banner newspaper. His job involved the physical production of the newspaper, not writing for it.

In his spare time, Pelley wrote fiction. He created stories about a fictionalized version of Bennington, which he called Paris, Vermont. The proceeds from his four novels and the many short stories that appeared in popular magazines easily outstripped his $16 weekly salary at the Banner.

A couple of years later, Pelley was able to purchase a St. Johnsbury newspaper called the Caledonian at a steeply discounted price, because it had fallen on hard times. To serve the community properly, Pelley declared, a newspaper “must have no politics and no religion.”

After only a year in charge, Pelley was ready to move on. The Methodist Episcopal Church hired him to study its missions around the world. His tour brought him to Europe and Asia, where he witnessed brutality related to the Russian Revolution. Pelley believed the false claim that the revolution had been incited as part of a vast Jewish conspiracy. He returned to America deeply anticommunist and antisemitic.

Having sold the Caledonian, Pelley moved to California, where he wrote scripts for the movie industry. But during his time in Hollywood, Pelley said he had a transformative experience. He claimed he had died and gone to heaven for seven minutes. During that time, he said, he met God and Jesus Christ, who told him to help bring about a religious transformation in the United States. Pelley interpreted the instructions to mean he should move to North Carolina and publish a Christian, fascist magazine.

When the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, Pelley was ready, launching a paramilitary group called the Silver Legion in North Carolina. Its members were dubbed the Silver Shirts, inspired by Hitler’s brutal Brown Shirts.

In 1936, like a real-life version of Buzz Windrip, Pelley ran for president. Unlike Windrip, he only managed to get on the ballot in one state and won 1,600 votes.

Pelley was called before the recently created House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1940 and accused of “fulsomely praising Hitler and of advocating dictatorship, vigilantism, and segregation of Jews.” A federal agent testified that Pelley had told her that he planned to organize a march on Washington, take over the government and implement Hitler’s program.

Two years later, with the United States having entered World War II, the federal government arrested Pelley and charged him with a dozen counts of making false and seditious statements, intent to cause insurrection within the military, and intent to obstruct military recruitment. A federal prosecutor called him “a tool of Axis propaganda.” The jury at his trial in federal court in Indiana convicted him on 11 counts. The judge sentenced him to 15 years in prison.

Pelley’s trial made news around the country. His career was finished and newspapers referred to him as the very thing that Lewis had warned about—a would-be American dictator.

For more on Pelley, see this 2018 review of his work from the Walloomsack Review.