Doctors knew when the outbreak had started — June 17, 1894 — but they didn’t know what had broken out.

The symptoms of the many cases erupting in Rutland County that summer varied so much that they made doctors unsure of the diagnosis. A three-year-old boy, labeled Case 1, was a previously healthy, active child who developed a moderate fever and appeared to have indigestion. After three days, his fever broke, but he could no longer walk. After 10 days, he started to move about by holding onto chairs. Then, after three weeks, he regained full use of his legs.

Another child, a six-year-old boy, Case 64, had also been in good health when he developed a high fever, accompanied by vomiting. On the sixth day, he suffered paralysis in his right arm; the next day he could no longer move his left leg. Ten weeks later, he was no better — both extremities were still paralyzed and the muscles were weakening.

But he was more fortunate than a six-year-old boy, Case 4, who suddenly began convulsing while playing in the street. The convulsions lasted hours. He also exhibited a moderate fever, rapid pulse and vomiting. The muscles in the boy’s neck and back became rigid and his arms and legs became extremely sensitive to the touch. On the sixth day, he died.

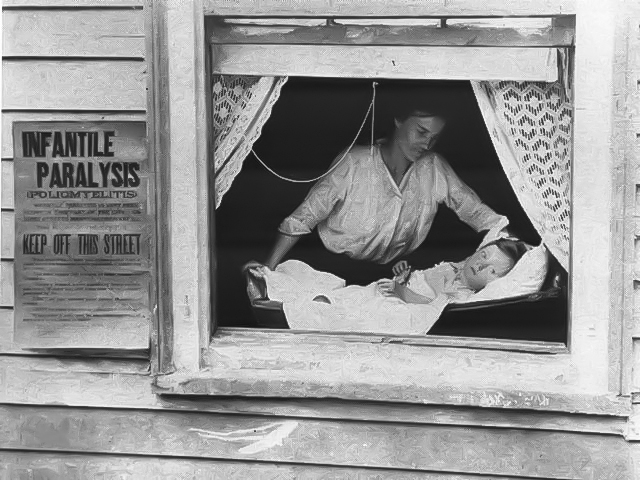

The alarming news surely spread more quickly than the disease itself. Newspapers carried brief reports about Vermonters who doctors believed had contracted meningitis. While the papers also covered a number of active epidemics, including smallpox, typhoid and measles, it wasn’t until late August that they connected the dots and reported that these suspected meningitis cases also represented an epidemic.

On Aug. 27, the Rutland Daily Herald reported that doctors believed an epidemic of cerebral meningitis, spinal meningitis and cerebro-spinal meningitis had hit the city and surrounding area. Over the past five weeks, the paper wrote, the outbreak had “been rapidly gaining headway until it has attained serious proportions.”

Fatal cases or ones leading to total paralysis were relatively rare, doctors told the newspaper. However, they noted that many of the infected patients suffered paralysis in at least one limb and “the recovery of the patients (was) doubtful and slow.” Most cases seemed to be spinal meningitis “or a disease closely resembling it,” the Herald stated.

In the same article where it reported that the probable cause was meningitis, the Herald relayed a conflicting theory: “From information gained from physicians in the city yesterday it has been learned that polio-myelitis anterior [commonly known as polio]…seems to be the disease of the epidemic.”

This second diagnosis ultimately proved correct. Although it was buried in an article that was itself buried on Page 4 of the newspaper, the news was earth shattering: Vermont was suffering the first polio epidemic ever in the United States. In fact, this was the largest outbreak yet recorded anywhere. Although few people at the time had heard of polio, the disease would soon become a global terror.

News that it was polio that had broken out in Vermont came from Charles Caverly, a 37-year-old Rutland doctor. Caverly, who was educated at Brandon High School, Kimbell Union Academy and Dartmouth College before attending medical school at the University of Vermont, had recently become president of the Vermont State Board of Health. As such, Vermont doctors were required to send Caverly detailed reports of any cases they encountered of this perplexing and disturbing disease. Those descriptions enabled Caverly to diagnose the disease correctly as polio, rather than a form of meningitis, making him the first person to identify a polio epidemic. He communicated his findings to the American medical community

“Early in the summer just passed,” he wrote in the November issue of the Yale Medical Journal, “physicians in certain parts of Rutland County, Vermont, noticed that an acute nervous disease, which was almost invariably attended with some paralysis, was epidemic.”

Tracking the disease, Caverly wondered if geography might hold clues as to the source. The first cases were observed in the city of Rutland and the town of Wallingford. While most cases continued to arise in Rutland, they soon also emerged in other area towns. All but six of the reported cases occurred in the Otter Creek Valley, an area measuring roughly 30 miles long and 15 wide. The creek, contaminated with sewage and running at a particularly low level that summer, was a possible source. But Caverly believed he could rule it out. Most people who contracted the disease got their water from wells or mountain streams and springs. Similarly, “general sanitary conditions did not seem to have any influence on the epidemic,” he wrote.

Caverly considered whether animals were the source of the disease. He wrote that that summer, domesticated animals, including horses, dogs and fowl, had been dying of an “acute nervous disease, paralytic in its nature.” It was an intriguing idea. Subsequent research, however, has shown that polio only affects humans.

Polio didn’t appear to be contagious, Caverly wrote. He had received only one report where more than one family member had contracted the disease. But appearances were deceiving. It turns out that most people infected with polio are asymptomatic. (In later years, after studying more cases, Caverly came to accept that polio was contagious.)

Caverly and his fellow doctors faced a massive obstacle in understanding polio. At the time of Vermont’s epidemic, virology was in its infancy. The poliovirus wouldn’t be isolated for another 15 years. Researchers eventually determined that the virus is typically transmitted through contact with an infected person’s feces or through droplets from their sneezes or coughs.

Although Caverly failed to determine the cause of the outbreak, he provided helpful demographic information that showed the disease, which is sometimes called infantile paralysis, doesn’t only afflict the very young. In fact, he found that 15 cases were reported in people over age 14, including one case involving a 70-year-old. His statistics also showed that males were more prone to the disease; females only represented one-third of the Vermont cases. Research has since shown that both sexes are equally susceptible to contracting polio, but males are at higher risk of suffering paralysis.

After the 1894 epidemic, Vermont experienced a respite, with few cases emerging. Then in the summer of 1910, the state recorded 72 cases. Caverly, who remained in his role as president of the Vermont State Board of Health, was again on the case. A leading authority on polio, Caverly investigated a large outbreak in Vermont in 1916, which saw 64 cases. That year, more than 27,000 cases were reported in the United States, including 2,000 deaths.

In 1918, Caverly faced a new challenge: charting an epidemic of another frightening disease, a deadly influenza strain. Doctors had little recourse against the outbreak. No vaccine existed. They counseled bedrest and isolation, when possible, to limit its spread. That year, the new influenza killed an estimated 675,000 Americans. Among them was Charles Caverly, who died in October at the age of 62.

He only lived long enough to see the start of the enormous damage polio would inflict, and he didn’t get to witness the medical miracle that all but eradicated the disease. Each summer, parents braced for the arrival of polio season, when the disease always hit some part of the United States and spread overseas. Adults were also susceptible, including future president Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who contracted polio in 1921 at the age of 39.

Fear of polio was part of everyday life. Public officials closed beaches, swimming pools and amusement parks in an effort to stop the spread. Parents warned their children not to drink from water fountains.

Doctors found that roughly one out of 200 polio infections led to irreversible paralysis and roughly 5 to 10 percent of those cases proved fatal.

In the late 1920s, an artificial ventilator called an iron lung was invented, offering hope to patients who could not breath on their own because their chest muscles were paralyzed. The iron lung became the image many people associated with polio. Patients were slid into these cumbersome, sarcophagus-like machines with only their heads sticking out. Some polio patients required weeks or months inside an iron lung to recover use of their own lungs; others remained in an iron lung for life. The machines soon populated hospital polio wards — as well as the nightmares of parents and children.

Real hope of not just treating polio, but defeating it, arrived in the mid-1950s. Dr. Jonas Salk of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine had started work on a polio vaccine in 1948. By 1953, he was so confident of its safety and effectiveness that he vaccinated himself, his wife and their three sons. Two years later, on April 12, 1955, the American public learned that Salk’s vaccine had proved successful in clinical trials and would immediately be distributed. Across the country, communities celebrated the news by ringing church bells. Newspapers carried triumphant headlines. The Pittsburgh Press declared simply, “Polio Is Conquered.”

The polio epidemic peaked in the United States in 1952, with nearly 58,000 recorded cases. By 1957, the number of cases had dropped 95 percent to 5,485. By 1964, the number had fallen to 106 cases.

Today, thanks to Salk’s vaccine, which has been further refined, polio is largely a disease of the past. A global survey in 1988 found that there were still roughly 350,000 cases in 125 countries that year. Massive vaccination initiatives have lowered that figure to 62 known cases in two countries in 2024, or less than half the number of cases identified in the Otter Creek Valley in 1894.