Julius Wasmus faced death at close range. The American soldier leveling a musket at him stood so close his bayonet pressed against Wasmus’ chest. Though he spoke no English, Wasmus understood when the soldier asked if he was British or German. Wasmus tried to explain that he was a surgeon from the German principality of Braunschweig.

Then he blurted out three words that came to mind: “Freund und Bruder,” which perhaps fortunately for Wasmus sounded a lot like what they mean in English, “friend and brother.” Then he shook the American’s hand. “For what does one not do when in trouble?” Wasmus later explained.

The American lowered his gun, took the surgeon’s pocket watch and then offered him a drink. With that, Wasmus’ involvement in the Battle of Bennington, as it would become known, and the Revolutionary War were over. He would spend the coming years as a prisoner of war.

We know of his experience, because, of the nearly 4,000 men who took part in the battle, Wasmus gained a sort of immortality by the simple act of writing things down. His firsthand account, which lingered in a German military archive for two centuries before being translated into English, paints a picture of the tumult that enveloped the battle and then the town of Bennington in the immediate aftermath of the fight. It is the only surviving description of the battle by someone serving with the British.

Though hardly among the best known of the battles fought during the Revolution, the Battle of Bennington was significant because it weakened the British army, thus helping lead to the momentous American victory two months later at Saratoga, which ended a major invasion from Canada, boosted patriot morale and prompted vital foreign aid for the war effort.

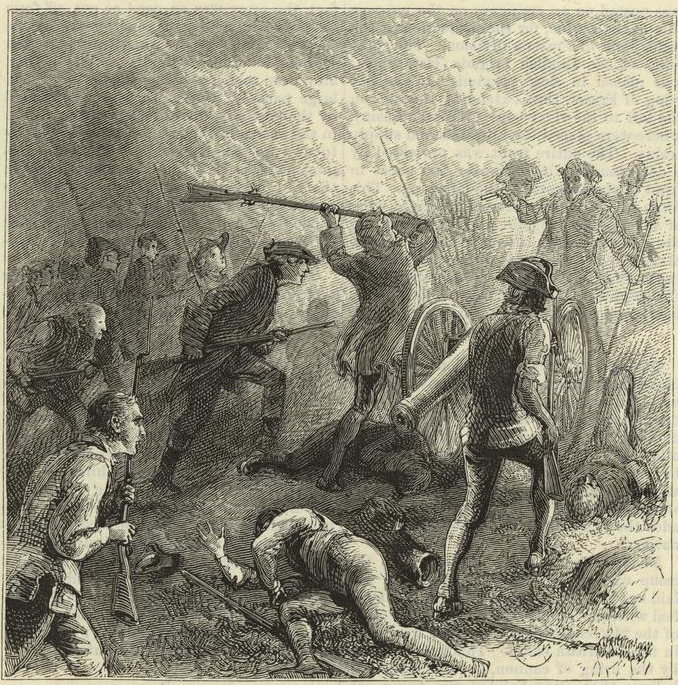

But all that was in the future. During the summer of 1777, British General John Burgoyne’s army was moving south as part of a plan to cut the New England states off from the rest of the Colonies. On August 16, Burgoyne sent a detachment under the leadership of Lt. Col. Friedrich Baum, a German officer, to capture “large supplies of cattle, horses and carriages” held by the Americans at Bennington. Fighting erupted when Baum’s unit, made up of German, British, Loyalist and Native fighters, was met by American forces led by Brig. Gen. John Stark.

Wasmus’ unit was on high ground, dug in behind earthworks, but its situation was tenuous. Colonial troops were encircling them. Sheltered behind a large oak tree, the surgeon treated the wounded. Wasmus watched as some of his unit’s elite soldiers fired volleys at the Americans, “(but) as soon as they rose up to take aim, bullets went through their heads. They fell backwards and no longer moved a finger. Thus, in a short time, our tallest and best dragoons were sent to eternity.”

The situation only grew more desperate. The unit’s lone cannon fell silent when all members of its crew were killed or wounded. “We withdrew now with great speed while I was still busy dressing wounds,” Wasmus wrote. He made it about 250 yards before stumbling over a large, fallen tree. Rising, he saw Americans clambering over the earthworks. Three fired at him. “I again fell to the ground behind the tree and the bullets were dreadful, whistling over and beyond me,” he wrote. “I remained lying on the ground until the enemy urged me rather impolitely to get up.”

Wasmus initially thought he was the only one who had been captured. He cursed himself for not retreating sooner and faster, but was relieved to learn he was far from the lone prisoner. In fact, he was one of more than 700 troops taken captive by the Americans that day. Those numbers, plus the estimated 200 killed, brought British losses to slightly more than 900, a severe blow to the invasion force.

Realizing that Wasmus was a surgeon, an American militiaman led him over to treat his son, who had been shot through the thigh. Wasmus was then ordered by General Stark to bandage several more Colonial soldiers. Wasmus instinctively raced instead toward wounded German troops, and was horrified when the Americans stopped him from treating them.

“To see a friend or fellow creature lie bleeding on the ground who has been cruelly wounded by the murderous lead and approaches his death shaking, crying for help, and then not be able, not be allowed to help him, is that not cruel?” he wrote.

When Wasmus started packing up his medical instruments and bandages, his captor took them from him and instead offered the surgeon a drink of rum from a wooden flask that hung from his neck. Wasmus noticed that the Americans were dressed informally compared to the British and Germans, wearing shirts, vests and long linen trousers that reached their shoes, which they wore without socks. In addition to their guns, the Americans carried powder horns, bullet bags and those flasks of rum. All the Americans he encountered appeared hardy, being “of very healthy appearance and well-grown.”

By late afternoon, Wasmus was on the road to Bennington, about 10 miles away. “My guide kept holding me tight by the arm, particularly when he was noticed by his countrymen,” he wrote. In the distance, they could hear cannon and gunfire, which he would later learn was American forces battering reinforcements who had arrived too late.

Along the way, Wasmus encountered a cart carrying Lt. Col. Baum, who had been shot through the abdomen. When the cart reached North Bennington, Wasmus and others helped the officer into a house. Baum asked Wasmus and another surgeon to stay with him, but the American guards made the surgeons keep moving. Baum would die two days later.

German troops were fighting in America because various ruling princes had sold their services to the British army. “The Americans used to consider us unbeatable and did not believe they could capture our regular troops, but what will they now say about us!” Wasmus wrote. “Will they keep on running away from us in the future?”

Wasmus was unimpressed by the sight of an American major adorned with the spoils of war. The officer wore a Braunschweiger grenadier’s cap and a gorget (a silver throat covering worn by officers as a sign of rank), and carried the long, straight sword of a German dragoon. “One can well get an idea of the simplemindedness of these creatures,” he wrote.

One of the surgeon’s fellow prisoners, a British officer serving with the Germans, informed the American major that Wasmus’ captor had taken some of his possessions. “(A) quarter of an hour later my guide came and presented me with my things in a most polite manner,” Wasmus wrote, “they were not embarrassed at all.”

The return of these possessions did little to calm Wasmus’ nerves. “The future frightens me,” he confessed. “To all appearances, we live here under a nation extremely enraged, whose language none of us understands; each one is asking what will become of us.”

That night, however, Wasmus was relieved to be taken to a house with other prisoners and fed beef, pork, potatoes and punch. After the meal, he reported, the captives agreed that they would be “satisfied if we will not be treated any better or worse during our imprisonment.”

Partway through the meal, an American officer had sat down next to Wasmus. It was Col. Seth Warner, whose Green Mountain Boys had devastated the German reinforcements earlier in the day. Warner pulled out a small metal box containing a dozen lancets, which Wasmus recognized as his own. With the British officer again acting as translator, Wasmus asked for his lancets back. Warner handed over half the lancets and kept the rest “as something very peculiar.” Warner also returned Wasmus’ journal to which the surgeon later added details from that eventful day. Despite the situation and the lack of a common language, the Americans who he ate with “behaved with extreme politeness and civility toward us.”

The next day the prisoners were taken to Bennington, a community transformed by war. The town, which had been settled 16 years earlier by a group of 22 English colonists, was now home to nearly 600 residents. But recent reports of Burgoyne’s invasion force moving on Albany had brought an influx of civilians fleeing the fighting. The population ballooned when Stark’s New Hampshire brigade of well over 1,000 men arrived, followed by hundreds of members of militias from Vermont, Massachusetts and New York.

After the battle, the American forces had to figure out what to do with their more than 700 prisoners. The decision was made to hold them in various locations around town, but the majority, an estimated 400 to 480 Germans and Canadians, were crowded into the town’s small meetinghouse.

Julius Wasmus was fortunate. Though he wasn’t an officer, he was housed with them upstairs, under guard, in the town’s Catamount Tavern, which had been a gathering place for opponents of New York land claims before the war and now for supporters of the American cause. “The inhabitants of this province were said to be the worst Rebels,” he wrote, “they made disagreeable faces and perhaps did not wish to express themselves in overly refined terms toward us; but to our comfort, we could not understand them anyway.”

Wasmus learned that the tavern’s owner, Stephen Fay, had had five sons fighting in the battle and that two of them had been killed. (In fact, only one, John, had actually died.) “All in the house were very sad and our presence was probably very disagreeable to these people,” he wrote.

On their first night in Bennington, Wasmus and another German surgeon, Friedrich Sandhagen, were invited by an American doctor to dine at the nearby home of a local militia leader. Just as they were sitting down, a loud commotion erupted outside. Shouts were coming from the direction of the meetinghouse. The Americans in the room rushed to investigate, leaving the surgeons stunned and alone.

The two Germans decided it would be safest to return to the Catamount Tavern, but on the way they encountered a group of militiamen hurrying toward the meetinghouse. A Massachusetts minister, Thomas Allen, stepped from the crowd and attacked Sandhagen, hitting him 40 or 50 times with the flat of his sword. Suddenly Wasmus himself was grabbed from behind. He turned to see the American major whom he had seen the day before wearing some spoils of war. The major came to the Germans’ defense, ordering Allen to stop and immediately taking the surgeons to the meetinghouse, where they were needed to treat the wounded.

The uproar from the meetinghouse had been the sound of panic. Prisoners inside had heard the loud crack of breaking wood and, fearing that the building’s second-story gallery was collapsing, had rushed the doors. Some made it outside.

Guards, believing the prisoners were trying to escape, fired into the terrified mass. Other American soldiers raced to the meetinghouse, clubbing prisoners and threatening them with bayonets to force them back inside. In the commotion, five prisoners apparently escaped. Two were killed by musket fire and five others wounded. Wasmus speculated that the noise that had prompted the pandemonium was the snapping of a wooden board that had been placed over a pew to accommodate more prisoners.

Wasmus and Sandhagen tended the wounded and stayed the night in the meetinghouse. “In spite of everything, our dinner was not lost,” he wrote. “The doctor (who had invited them to dine) called on us and we ate on the pulpit.”

Wasmus had wanted to remain in Bennington to care for the wounded, but two days after arriving in town, the surgeon was part of a group of prisoners headed toward Boston. Most of the prisoners were provided horses, including the wounded officers. They made their way south through Pownal, Vermont, and on toward Williamstown, Massachusetts. “We were no longer treated as prisoners on our march. We rode and went as we pleased,” he wrote.

The treatment by locals couldn’t have been more different than immediately after the battle. “We understood no English but they treated us like friends, spontaneously offering us milk and beer,” Wasmus wrote.

Perhaps the novelty of seeing the enemy at close range had elicited this unexpectedly warm reception. “In front of all the houses that we passed,” he wrote, “stood people who looked at us with the same intense curiosity as the people in Germany when the first rhinoceros arrived there.”

Postscript: Julius spent the next four years in central Massachusetts, treating his fellow German and British captives before being freed in a prisoner exchange.