Last month, Jessica Wood, the director of the School of Nursing at Norwich University, introduced a reporter to Arthur, a child lying in a hospital bed on the Northfield campus.

Normally, medical privacy protections might prohibit such an introduction. But Arthur is no ordinary patient — he’s a medical mannequin, or manikin, a tool for nursing school students to learn to perform diagnoses and procedures in a safe and controlled setting.

“We just got Arthur,” Wood said. “He’s our pediatric simulator.”

Arthur is part of a haul of brand-new equipment — including manikins and virtual reality goggles — funded by nearly $500,000 in federal appropriations awarded to Norwich last fall.

It comes as the federal and state governments invest millions of dollars in Vermont’s nursing programs, intended to combat the state’s chronic nursing shortage.

In Norwich’s case, it’s an investment that will help address one of the thorniest challenges that nursing programs across Vermont are facing. It’s an obvious, though paradoxical, problem: the shortage of nurses is making it more difficult for nursing schools to graduate more nurses.

The tight labor market makes it difficult for universities to find people to teach nursing classes. And at short-staffed medical facilities, clinical placements — in which students gain real-world medical experience under the supervision of practicing nurses — can be hard to find.

“This is just another illustration of the workforce crisis that we’re dealing with,” said Devon Green, a lobbyist for the Vermont Association of Hospitals and Health Systems. “So we need to get new students in, but for that we need to have people who are able to train (them). For that we need workers in the hospitals. And someone needs to train those folks.”

In high demand

Vermont is projected to need thousands of new nurses in the coming years — roughly 5,400 in the next two years alone, according to a report released earlier this month by the Vermont Business Roundtable Foundation.

The shortage has ripple effects across Vermont’s health care industry. It’s exacerbated wait times and access to care. Long-term care facilities are leaving beds empty because they have no nurses to staff them. Medical providers have relied on travel nurses working on expensive short-term contracts. Hospitals have raised prices for medical procedures — costs that are in turn passed on to insurers, employers, individuals and taxpayers.

The good news is that Vermont nursing education programs are in high demand. Some nursing programs in the state have waitlists, and loan incentive programs for nursing schools have run out of money.

“The demand is exceeding the capacity of the nursing programs in Vermont, at least as they’ve been currently configured to produce nurses,” said Scott Giles, the president and CEO of the Vermont Student Assistance Corporation, which offers multiple loan and scholarship programs tailored toward nursing schools.

That demand, as well as a surge of pandemic-era federal dollars and growing recognition of the state’s need for nurses, has set the stage for a wide-ranging investment in Vermont’s nursing schools programs.

Last fall, Norwich touted a new $487,000 appropriation secured by U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., as a way to “propel workforce development efforts in this critical sector.”

Vermont State University is renovating multiple campus facilities to increase the size of its nursing program — an expansion funded through $800,000 in state appropriations and $6.3 million in federal money secured by former U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt.

And last month, UVM announced the creation of a new nursing master’s program geared toward students seeking a career change.

That doesn’t count the millions appropriated for scholarship and loan programs for health care professions — over $20 million as of November, according to the state auditor’s office.

“A lot of states are really trying to figure out, whether it’s through state funding or federal funding, how can we make it less of a burden for people to enter the field?” said Shiela Boni, the nursing executive officer at Vermont’s Office of Professional Regulation. “I haven’t in my career seen as much financial resource being put into health care workforce initiatives.”

‘Fiscally, financially, they just can’t do it’

But Vermont’s nursing programs are constrained by formidable bottlenecks — largely due to the same shortages their graduates could help alleviate.

The high demand for nurses means that nursing schools seeking to hire teaching faculty are competing with hospitals and other facilities, providers that are themselves increasing salaries and benefits to attract applicants.

“There’s just constantly not enough nurses who want to go into the education role,” said Jennifer Laurent, who oversees nursing graduate programs at the University of Vermont.

In order to become faculty, nurses generally need advanced degrees, an investment of time and money that can seem unnecessary — or unattainable — when lucrative opportunities are widely available. Laurent, who also chairs the Vermont Board of Nursing, said she took a $20,000 pay cut when she started at UVM.

“There are a lot of people who can’t take that kind of cut,” she said. “It’s not that they don’t love teaching, and it’s not that they don’t love working with students. It’s fiscally, financially, they just can’t do it, especially now.”

And at increasingly desperate hospitals and health care providers, practicing nurses also have an array of opportunities to make extra cash, including sign-on bonuses and higher pay rates for weekends and holidays.

“Particularly over the last 10 years, the rift between what educators are paid and what clinical nurses are paid has grown considerably,” said Rosemary Dale, the chair of UVM’s nursing department. “To the point that it makes education not the most appetizing job from a financial standpoint.”

A ‘juggling act’

Last month, Sarah Truckle, Vermont State University’s vice president of business operations, testified in the House Health Care Committee about the university’s expansion plans. The multi-campus public university is planning to add about 100 students a year for the next three years, bringing its total nursing student body from around 670 to 1,000, Truckle explained.

Rep. Lori Houghton, D-Essex Junction and the chair of the committee, jumped in with a question.

“Do you have the clinical placements for these additional hundred?” she asked.

The university, Truckle responded, is actively working on that.

“We don’t anticipate any major issues there,” she said. “But it is going to be an everyday, I think, juggling act of trying to find what works.”

Clinical experience, often called simply “clinicals,” is a key piece of nursing education. Most of that experience must come in real-world health care settings, involving hands-on work with real patients under the supervision of an actual practicing nurse.

But many short-staffed hospitals and facilities find it hard to spare practicing nurses to supervise and mentor students.

A mentoring relationship “notoriously slows you down in your practice,” said Laurent, the UVM nursing professor. “You may not be able to see enough patients. It’s a ton of work making sure that you’re really truly mentoring and teaching them. So there’s a lack of placements there.”

That can pit nursing schools against each other as they seek placements at a limited number of facilities with a limited amount of staff.

“We’re competing with UVM and Vermont State University, we’re competing with all these other people with LPN programs,” said Wood, of Norwich University. “We’re competing with lots of different people to get into these sites.”

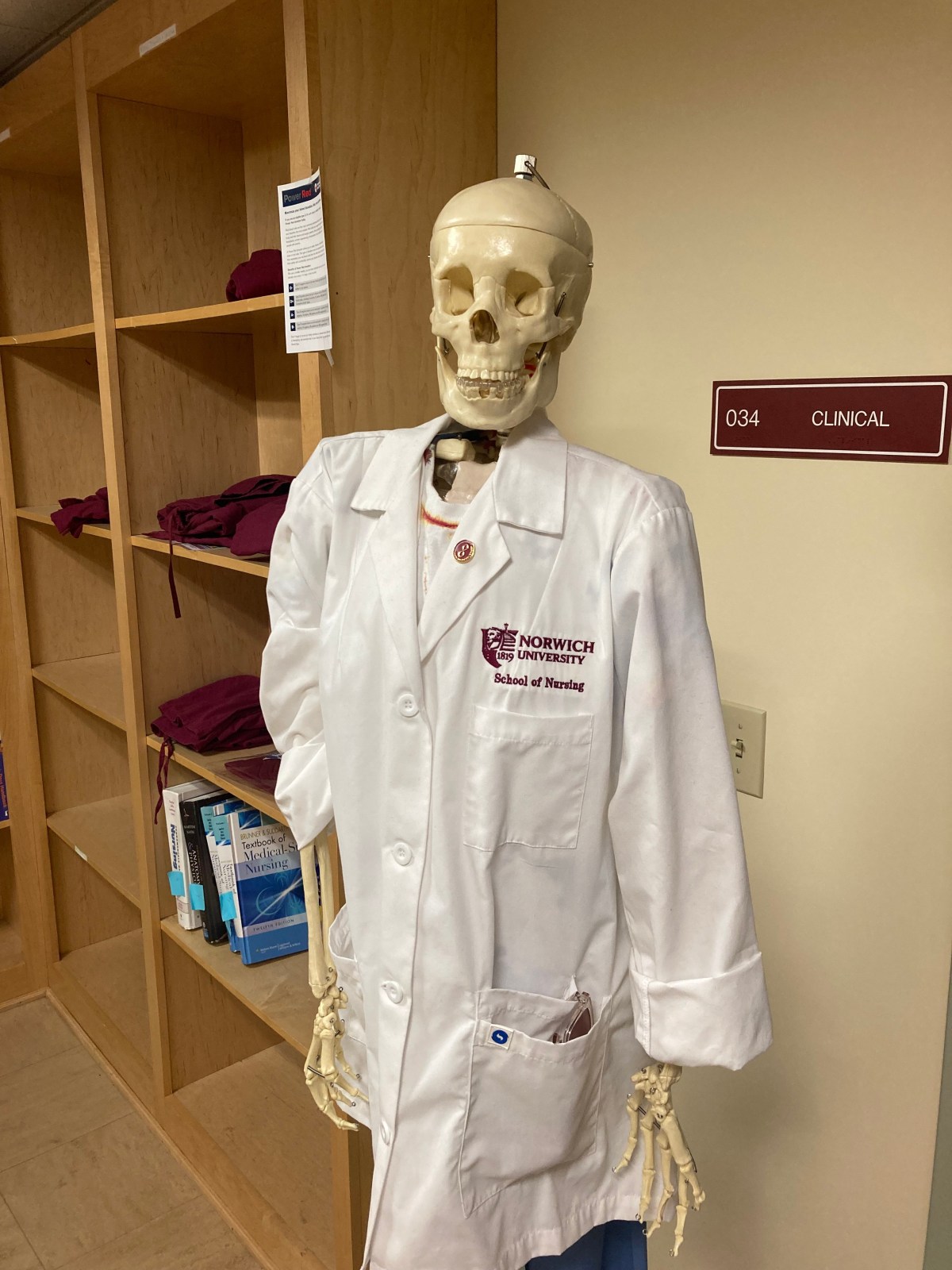

Amid that shortage, nursing schools are investing in new equipment, such as Norwich’s manikins and virtual reality goggles, that will allow them to do more clinical training through simulation.

Currently, Norwich students are allowed to obtain up to one-quarter of their clinical experience in simulated settings, according to Wood. Usually, students there do about 8% of their clinical hours via simulation, Wood said. But the new equipment will allow students to increase that percentage.

“If something happens and our clinical placement falls through, we need some kind of backup to ensure that the students have the experience they need,” Wood said.

Will it be enough?

Even as nursing schools and incentive programs have received an influx of money, some have raised questions about the effectiveness of those investments.

Doug Hoffer, Vermont’s state auditor, said in a report last year that the state did not have enough data to show how effective its health care-oriented scholarships and loans were. Much of the funding for those programs consists of temporary federal dollars, he also noted, and it’s not clear how much will be replenished with state funds.

And Deb Snell, the president of AFT-Vermont, which represents thousands of Vermont health care workers, said that the state needs not just recent graduates of nursing schools, but practicing nurses from elsewhere in the country.

The state’s nursing workforce — like its general population — is aging, Snell said. At UVM Medical Center, where Snell works, 200 nurses are at or near retirement age, she said.

“A lot of nurses in the state, I think, are roughly 55 or older, or at least over 50, and are thinking of leaving the profession sooner rather than later,” Snell said.

What’s more, she noted, not all of Vermont’s nursing school graduates stay and work in the state.

Vermont’s nursing schools — UVM, VTSU and Norwich University — currently graduate between 500 and 600 nurses every year.

But each year, roughly 50% of UVM’s approximately 100 undergraduate nursing program grads leave the state, according to the university, although nurses receiving UVM graduate degrees stay at much higher rates. At VTSU, about 80% of the roughly 350 nursing graduates each year receive a license to work in Vermont, the university said. And at Norwich, roughly 60% of the 242 undergraduate nursing school grads over the past five years received licenses to work in Vermont, according to the university.

“Even with us investing all this money in Vermont — which is great — we still need to find a way to attract nurses to our state,” Snell said. “Because I’m sure we can expand these programs. But I don’t know if Vermont will ever be in a position to grow enough nurses of their own to meet the need.”