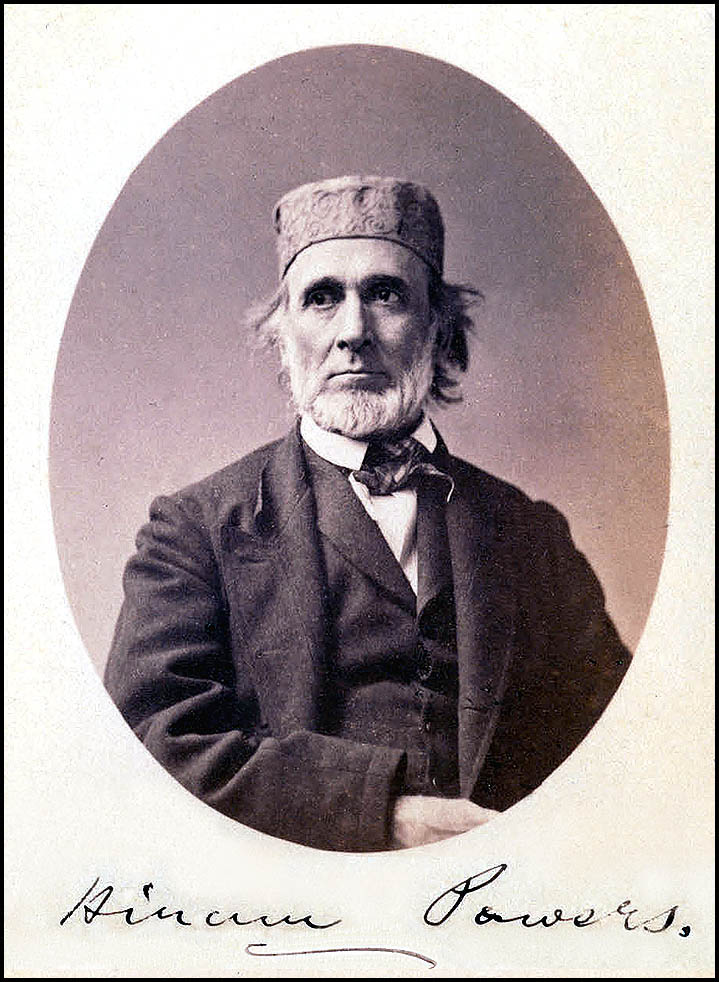

Hiram Powers is an exception to the rule that artists have to die before they become famous. The Vermonter, who lived and worked in Italy for most of his adult life, was internationally renowned by the time he was in his late 30s and is widely considered the most famous American sculptor of the 19th century.

Fame came at a price. His Florence studio became a required stop for Americans on the Grand Tour, the 19th-century tradition among the wealthy of visiting cultural sites across Europe. Period newspapers described Powers graciously greeting these streams of strangers attracted by his celebrity. It’s a wonder he got any work done at all.

Born in Woodstock, Vermont, in 1805, Powers grew up in a farmhouse overlooking the village. When Hiram was 12 or 13, his father lost the family farm in a bad business deal, so the family headed west in search of better fortunes, eventually resettling in Ohio. Despite the move, Hiram always considered himself a Vermonter; and years later he would connect his greatest success, the sculpture that made his international reputation, to a recurring childhood dream about a woman standing beside the Ottauquechee River.

At the age of 17, Powers was apprenticed to a Cincinnati clockmaker. He then used the knowledge he had gained of mechanisms in his work for the Western Museum, a sort of hall of horrors, to fashion automated wax figures for a frightening tableaux of Dante’s “Inferno.” By his early 20s, Powers was studying with a local sculptor, sometimes carving likenesses of his friends. A wealthy local businessman saw his work and became Powers’ benefactor, providing him with funds and letters of introduction to prospective buyers in major East Coast cities. In Washington, D.C., in 1834, he secured a commission from President Andrew Jackson. Though the resulting work wasn’t flattering — it was an honest depiction of an aging man — it led to more commissions from other leading politicians and judges.

Around this time, Powers gained another benefactor, who paid for him to travel to Italy. The trip would allow Powers, who worked in a Neoclassical style, to study the works of Renaissance masters. Italy would also provide easy access to flawless marble, and to skilled carvers to assist him in his work.

Powers settled in Florence, the former home of such celebrated sculptors as Michelangelo, Brunelleschi and Donatello. He had brought with him his family, as well as several incomplete busts of prominent Americans politicians to finish. He expected to be in Italy for several years. In the end, he never returned to the United States.

While in Italy, the concept for a new sculpture came to Powers. Part of the inspiration came from a recurring childhood dream.

“When a child in Woodstock and for years afterwards in Ohio,” he once explained, “I was haunted in dreams with a white figure of a woman white as snow from head to foot and standing upon some sort of pedestal below Uncle John’s house on the opposite side of the Quechee (Ottauquechee River). I could not get near to it for the water which seemed deep and roaring but my desire was always intense to come nearer. The figure seemed most lovely but not of a living person.”

One odd thing about the dream, Powers noted, was that “(a)t the time I knew nothing of sculpture nor had I ever read a word about it or even an idea upon the subject. I doubt if I had ever even seen a doll’s head.”

He stopped having the dream once he started sculpting, which made him wonder if the vision had been calling him to become an artist.

Powers completed a clay model of his dream statue in 1843. Artisan assistants then made a plaster cast of the clay model, and from that created a plaster model of the sculpture, before using a device called a pointing machine to meticulously fashion an exact copy in marble. The finished piece went on exhibit in London and made Powers the talk of the art world. Not only did it put him in the upper tier of international artists, it also brought respect from European connoisseurs for American artists in general.

The marble sculpture, which Powers titled “The Greek Slave,” was a life-size rendering of a nude woman with her wrists shackled. While nudes populated many works of art during the period, these were always in mythological or historical settings. Depicting a contemporary woman in the nude would ordinarily have been scandalous during the famously prudish Victorian era.

But Powers got around this by explaining in materials for the exhibition that far from being an object of erotic or prurient interest, “The Greek Slave” was in fact a symbol of Christianity, purity, modesty and victimhood. He described how the statue had grown out of his support for the Greeks’ recent struggle for independence. A little over a decade earlier, the Greeks had succeeded in overcoming the Turkish occupation of their country.

Powers explained that the woman in his piece was waiting to be sold at a slave market in Constantinople. “She is now among barbarian strangers,” he wrote, “… and she stands exposed to the gaze of the people she abhors, and awaits her fate with intense anxiety, tempered indeed by the support of her reliance upon the goodness of God. Gather all these afflictions together, and add to them the fortitude and resignation of a Christian, and no room will be left for shame.”

As proof of her faith, Powers included a cross hanging from the fabric draped over the post on which she rests one hand. A locket also hangs from the post, symbolizing love and fidelity. She demonstrates her modesty by using one hand to cover herself and by averting her eyes from the viewers’.

The sculpture struck a chord, mixing as it did nudity and sanctity, and highlighting the religious struggle between the Christian Greeks and Muslim Turks. There were also racial overtones, with Europeans and Americans backing the Greeks against the darker-skinned Turks.

Powers sold the statue before even completing it. A well-heeled captain in the British Army saw the unfinished work and quickly purchased it, promising to show it in England. Soon other wealthy Britons placed orders for versions of the statue. Each would have slight variations so there would be no mere replicas. In all, Powers would fashion six versions of the sculpture. And, fearing copycats, he applied for a patent to protect his work.

True to his word, the British officer allowed “The Greek Slave” to be exhibited in London, where it became an instant sensation, attracting thousands of visitors.

Soon another version of “The Greek Slave” toured the United States. The tour began in New York City, where one visitor wrote in a newspaper account: “The first few days there was a great scandal, but finally the prigs lifted their eyes and accustomed themselves to contemplating the artistic beauty in that looking glass of marble.”

The Rev. Orville Dewey, a prominent Unitarian minister in New York City, appreciated the religious imagery. In a sermon, the minister said the slave was “clothed all over with sentiment, sheltered, and protected by it from any profane eye.”

New York Daily Tribune publisher Horace Greeley exalted the piece: “(I)n that nakedness she is unapproachable to any mean thought. The very atmosphere she breathes is to her drapery and Protection.”

Some American venues proved less comfortable with the nudity, requiring men and women to view the sculpture separately.

In northern states, many people believed that though the title referenced a Greek slave, Powers was really making a statement about the inhumanity of slavery in the United States. In reality, that probably wasn’t Powers’ original intention. Over time, however, he became a strong abolitionist and eventually fashioned a version of “The Greek Slave” wearing manacles instead of chains, a subtle allusion to American slavery.

(A British sculptor, John Bell, riffed on Powers’ work, but made a more direct attack on slavery, exhibiting a statue of an African woman in chains, destined to be sold. He titled it “A Daughter of Eve — A Scene on the Shore of the Atlantic.” During the Civil War, he retitled it “The American Slave.”)

During the tour of “The Greek Slave,” Southern audiences also responded enthusiastically, apparently not seeing a parallel between the sculpture and the slavery system. When the sculpture was exhibited in New Orleans, one newspaper wrote proudly that “our country is the mother of him whose mind and hand are capable of adorning the world with imperishable gems, more valuable than diamonds.”

One tour organizer wrote to Powers that the show was raking in money from people of all nations, each apparently allowed to pay in his or her own currency. “There it was in piles: silver, paper,” he wrote. “There was the American Eagle glittering with joy at building his nest in your pocket; there was Queen Victoria, looking much prettier than when I saw her in London, her beauty heightened, no doubt, by her pleasure in serving you; there was the King of Spain …” Powers would see little of this money. He was swindled by his tour manager, but he did make enough to improve his studio. He also fortuitously put a few thousand dollars into the New York Central Railroad, an investment that helped secure his fortune.

“The Greek Slave” became arguably the most popular 19th-century sculpture by an American. It inspired poems by Elizabeth Barrett-Browning and John Greenleaf Whittier. Despite his efforts to patent the image, thousands of miniature reproductions were produced and were bought up by middle-class Americans trying to show their good taste. Author Henry James sniffed at the idea of a nude decorating the parlors of people who thought themselves respectable. He wrote sarcastically that the statue was “so undressed, yet so refined, in sugar-white alabaster … (that the owners ) could bring themselves to think such things right.”

“The Greek Slave” eventually made its way to Vermont in 1850. It was displayed in Burlington at a show timed to coincide with the University of Vermont’s graduation ceremonies. Then it moved to the hometown where Powers had first had the dream that helped inspire his creation. Though it stirred controversies in some parts, the sculpture sparked little fuss in Woodstock. Few people had attended the two-day opening, a friend wrote Powers, as it was haying season.

Postscript

“The Greek Slave” also managed to make headlines in the 21st century, proving it still had the power to divide opinions. In 2004, staff for Gov. Jim Douglas asked that a recently created desk lamp depicting “The Greek Slave” be removed from the governor’s ceremonial office in the Statehouse. A spokesperson expressed concern that a visitor might knock over the lamp and added that he didn’t want the governor to have to explain to schoolchildren what a naked Greek slave was doing on his desk. The lamp was moved to the neighboring Cedar Creek Room.

When he took office in 2011, Gov. Peter Shumlin had the lamp returned to the ceremonial desk. Meanwhile, replicas of Hiram Powers’ iconic piece had been adorning the Statehouse all along: four small copies of the statue are part of the elaborate chandelier that was installed in the House chamber during the sculptor’s lifetime.