Six years after the closing of the Windsor prison, regional leaders are considering a mixed-use concept for the unused, state-owned property, including roughly 100 housing units.

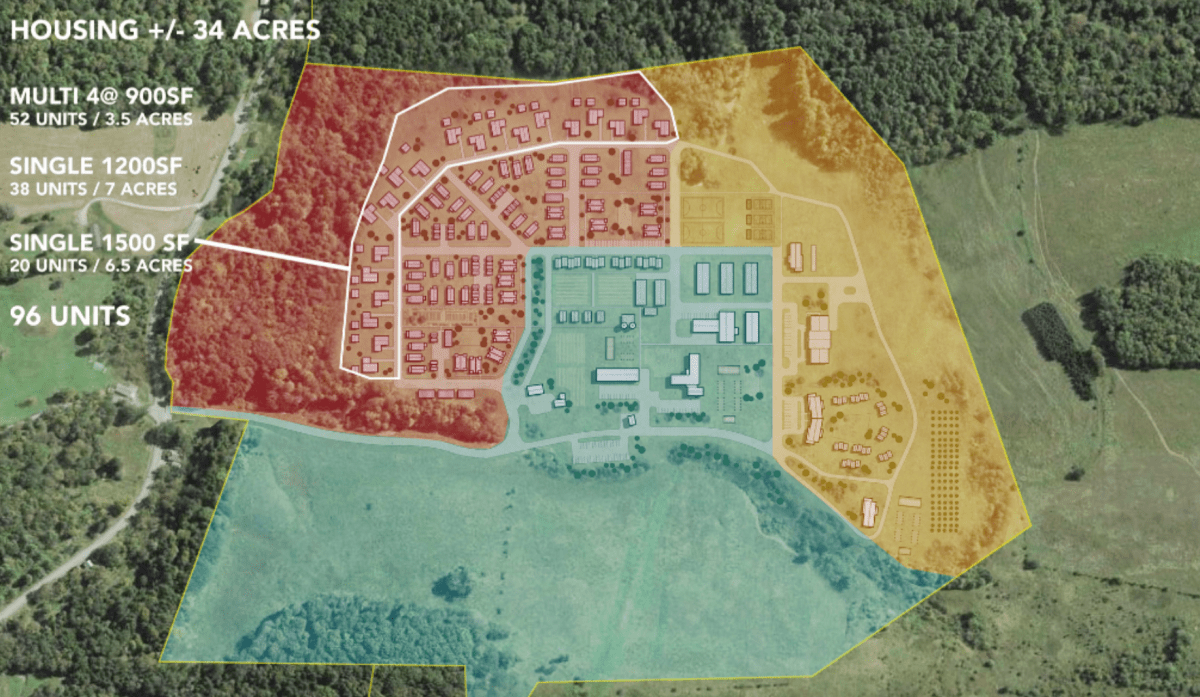

The latest idea proposes about 50 apartments in multi-unit buildings and almost 60 single-family units, all of which would spread across more than 30 acres.

Business, light industrial, and dormitory or dining uses would take up 57 acres in the proposed concept and require the demolition of some structures. Recreational space would take up the remaining 27 acres.

In a series of public meetings this month, Thomas Kennedy, the Mount Ascutney Regional Commission’s director of community development, and Emily Bell, principal of Bell Design Studios, which crafted the design on behalf of the state, presented Windsor residents with a planning study that includes the housing proposal.

Bell said she would modify the plans based on feedback before presenting them to legislators this session. Depending on where the project goes, it could require approval from the state, town or both.

“The feedback is the next step in building what we want to bring to the Legislature,” Bell said during one of those presentations, on Dec. 13. The meetings were first reported by the Valley News.

Southeast State Correctional Facility closed in 2017, ending the 208-year-long presence of prisons in Windsor. Maintaining the property costs the state about $250,000 per year, according to a 2021 legislative report studying uses for the site.

The 118-acre farm-style property, surrounded by 826 acres of undeveloped state land, sits three miles from downtown Windsor. Structures still exist on the property from its former use, ranging widely in their condition, including silos, multiple dormitories, offices, and a light manufacturing building, according to the latest study.

Since the prison’s closure, state and local officials have repeatedly explored possibilities for the property, including a 2021 pitch by Gov. Phil Scott to sell it, which was rebuffed by lawmakers.

Last year, two bills proposed using the former prison as a 10-bed juvenile detention facility, potentially filling a void left by the closure of the Woodside Juvenile Rehabilitation Center in 2020. That idea proved unpopular with Windsor, and a recent Vermont Supreme Court decision has paved the way for a proposed youth facility in Newbury, about an hour north.

The primary takeaway of years of feedback, Windsor Town Manager Tom Marsh said in an interview, was that residents did not want another prison or similar corrections facility.

Now, as the town again considers what it hopes to see in the former prison, Marsh said the conversation is a step toward action.

“In the past, most of the ideas had focused on a single use of the 118 acres,” he said, calling previous investigations “much more nebulous.”

Summing up the month’s conversations, Marsh noted that some residents want the property to remain vacant, largely in an effort to help wildlife in the area. But the presence of utilities — town sewer, significant water storage, power — makes a strong case for development, he said.

“My impression is that there would be an interest in a sensible development. Something that took into account the natural aspects of the area,” he said, adding that he believed a “significant majority” of residents would support a multi-use concept with housing.

Residents at one of the public hearings last week expressed a range of reactions to the idea, the Valley News reported, from support of the concept to favoring lower-density housing or no development at all.

Despite progress, any change to the Windsor property is far from happening. In addition to requiring state approval, housing construction would require local zoning changes and state permits, not to mention finding a developer willing to take on the project.

Organizers plan to present their concept, modified based on resident feedback, before the Legislature this session. Marsh expects it could take a decade for such a project to be completed, but the latest vision could finally spur the state into making a decision.

“We’re not talking about corrections, we’re not talking about a knee-jerk reaction,” Marsh said. “We’re talking about a plan that, however it fleshes itself out, could have some benefit.”