Two hundred years ago, a small boat was making big news. Under an enthusiastic, one-word headline (“Canals!”), a national magazine reported: “A sloop, called the Gleaner, has arrived at New York from St Albans, in the state of Vermont.”

The vessel could carry up to 60 tons of merchandise (it reached the city with 1,200 bushels of wheat and 40 barrels of potash) and “does not appear to have had any difficulty in passing through the northern canal,” the Niles National Register informed readers.

“(The Gleaner) is designed as a regular packet [that is, offering scheduled service] between St. Albans and the city of New York.” In case readers had missed the significance, the magazine breathlessly added: “Look at the map! An uninterrupted sloop navigation from one place to the other!”

The writer can be forgiven the heavy use of italics and exclamation points: This was important news. The Gleaner was clearly just the beginning, the first of countless boats that would use this newly constructed route, the Northern Canal, which connected Lake Champlain with the Hudson River and, therefore, with New York City.

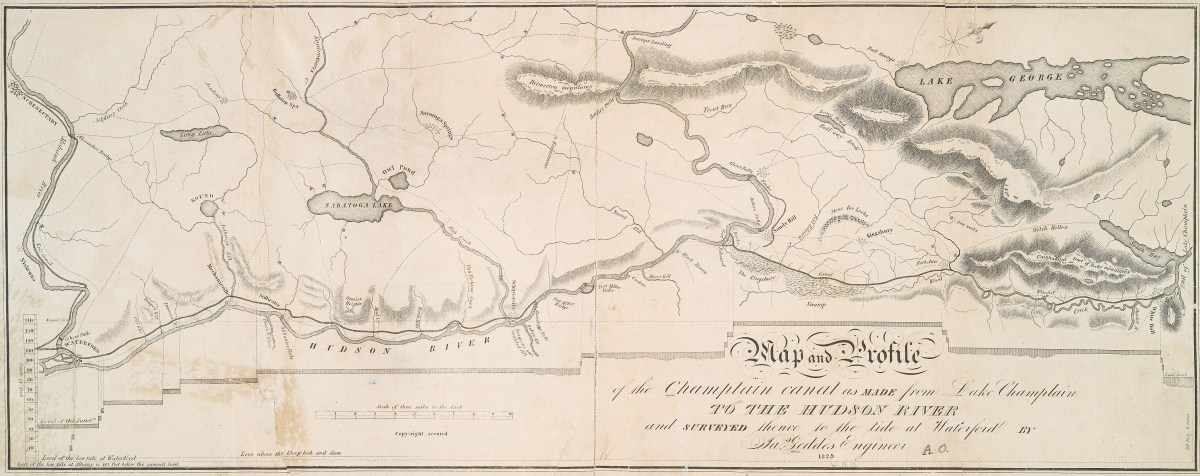

The Gleaner’s journey took place in September 1823, just as construction of the roughly 60-mile water route, more commonly called the Champlain Canal, was being completed. The boat’s owners were apparently so eager to make history that their voyage south was delayed for several days at Waterford, New York, while the locks there were being finished. It was like being the first to drive on a new interstate highway and then having to pull over and wait for one final bridge to be completed.

The New-York Evening Post explained to readers the significance of the new canal, using distinctive 19th-century spelling and diction: “To shew at a simple view, the importance of this intercourse with the interior of our country, it is only necessary to state that merchandize can now be transported by this conveyance, to and from St. Albans, in from 10 to 14 days, at an expense of about ten dollars per ton. Hitherto the time required for carrying merchandize from this city to that place, has been about 25 to 30 days, at an expense of 25 to 30 dollars per ton.”

In short, the canal would cut shipping times roughly in half and shipping costs by as much as two-thirds. Technological advancements rarely bring such sudden and drastic savings.

Another thing to notice about that quote: At the time, Vermont was considered “the interior of the country.” That’s understandable. For most Americans, there was no easy way to get there. Roads were poor; they were bumpy, rutted and seemed to alternate between dusty and muddy. Lake Champlain was handy, but you had to trek to its shore to take advantage of it.

No one anticipated the potential of the Champlain Canal better than Nehemiah Kingman and Julius Hoyt. The St. Albans merchants understood that its opening would provide them access to new markets along the canal’s route, and more importantly along the Hudson River, including Troy, Albany, Poughkeepsie and finally New York City. They designed their boat, which measured 60 feet by nearly 14, to fit the new canal, and they added some indispensable features.

Sailboats were great for open water, but once they reached a canal, they would have to shift their cargo to a waiting canal boat, which was a time-consuming process.

Instead, Kingman and Hoyt devised a canal boat with a sailing rig so it could be wind-powered on the lake. But once it reached the canal, the crew could lower the mast and raise the centerboard, which otherwise would have ground into the base of the canal. The Gleaner was designed to maximize its carrying capacity. Its draft was 3 and a half feet, leaving only 6 inches clearance in the canal’s shallowest parts, which were originally 4 feet deep.

Once within the canal, boats were drawn by horses or mules. In addition to its impressive cargo capacity, the Gleaner could sleep 10, which would have been a mix of crew and passengers.

New York’s Mercantile Advertiser praised the intelligence of the design: “The vessel was built for an experiment, and is found to answer all the purposes intended. She sails fast and bears the changes of the weather in the lake and river as well as the ordinary sloops, and is constructed properly for passing through the canal.”

The St. Albans boat had reached New York first, before the boats “of some of the more southern places on the lake,” the paper noted, “but will, no doubt, soon be followed by them.” It would shortly also be imitated by them, as merchants around the lake created their own versions of a sailing canal boat.

The cost of the canal had been borne by New York state, which would recoup the expense by imposing tolls. The project had taken five years to complete. Another, much larger project, the 363-mile Erie Canal, would be completed in 1825 and connect Lake Erie and the Hudson. Together, the two canals would knit together the region into a cohesive economic network.

Vermont merchants had previously relied on trade with Canada, but that commerce waned when Britain levied import tariffs in the aftermath of the War of 1812. Needing to replace that market, merchants looked elsewhere, including the Hudson River Valley and New York City. But with wagons and stagecoaches as the main means of transport, there was no cost-effective way to get heavier and bulkier products to market.

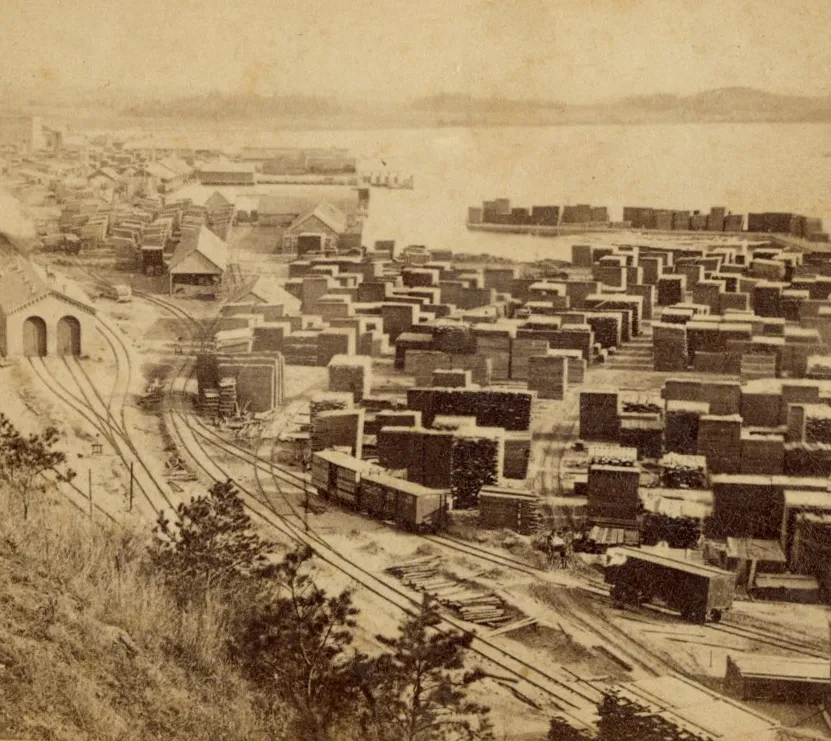

The opening of the Champlain Canal meant trade with Canada would essentially stop, as Vermonters found new markets to the south for their lumber, marble, and agricultural products. In the first five years of the canal’s operation, the number of shipping vessels on Lake Champlain would increase roughly fivefold, to about 200. Wharves would spring up along the shoreline to accommodate the growing merchant fleet; sawmills would be built to process lumber being harvested for market.

The success of the canal would also spawn a canal craze. Engineers would propose an array of ambitious — some would say preposterous — projects to crisscross the state. One plan would call for a canal to connect Lake Memphremagog and the Connecticut River along a route rising more than 1,000 feet above either and requiring drilling a 2-mile-long tunnel through a hillside in Walden. In the end, none of these fanciful proposals came to fruition.

But all that was in the future. September 1823 was a time to celebrate a new dawn. The Gleaner’s passage down the canal and then south on the Hudson was like a floating party. Celebratory volleys of musket fire and cannons announced its arrival and departure at communities along the route, where crowds gathered, delegations of local officials speechified and military bands played.

The party atmosphere was still going strong when the boat docked in New York. In a story headlined “The Vermont Ship,” the Commercial Advertiser announced the vessel’s arrival in the city, proudly stating, “We have this morning been on board of the Gleaner.”

The writer seems to be still buzzing with excitement as he suddenly interrupts the flow of his story: “Just at the moment of writing this paragraph, we are reminded by the noise in the street, that that part of the cargo of the Gleaner, in barrels, is passing before our door, on its way to the proper office for inspection. Forty cartmen have volunteered on the occasion, each taking a barrel and forming together a procession. A flag floats over the van of the procession, and the horses tramp, and carts rattle to the tune of martial music.”

Not to be outdone for enthusiasm about the changing times, the New York American declared: “Verily anticipation in our country can scarcely keep pace with reality.”

If the opening of canals felt like a sudden transformation of daily life, imagine what people would have thought if they had known the changes railroads would bring just a quarter-century later.