A new report by the Energy Action Network analyzes Vermont’s climate emissions using new framing, and paints a damning picture of the state’s contribution to climate change and its progress toward reducing emissions.

There are several ways to understand the amount of climate emissions produced by a state, country or other entity. One is its total emissions, or the amount of greenhouse gases it produces in a given year. Another is the amount of emissions produced per capita, or per person. Still another is the entity’s cumulative emissions, or the emissions it has produced throughout its history.

In 2019, Vermont produced fewer total climate emissions than any other Northeastern state — 8.8 million metric tons of climate pollution, according to the report, compared to the 240 million metric tons of climate pollution produced in Pennsylvania, the top-emitting state. (Report authors used 2019 data because it was the most recent year for which consistent data was available to compare states across the Northeast.)

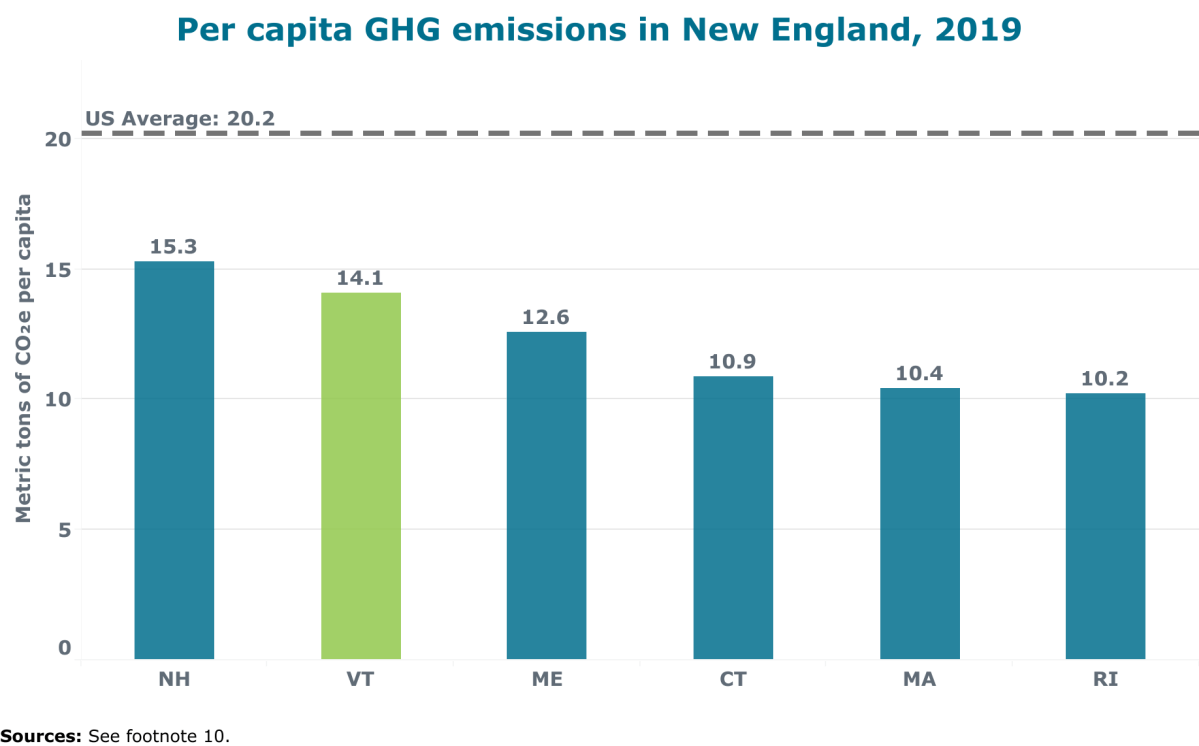

But — per capita — Vermont produced 14.1 metric tons of climate pollution in 2019. In New England, only New Hampshire had higher per capita emissions at 15.3 metric tons. Emissions include carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrochlorofluorocarbons, hydrofluorocarbons, ozone and other pollutants that trap heat when they’re emitted into the atmosphere.

Across the Northeast — including Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Vermont — Vermont had the third-highest emissions per person. Pennsylvania had higher per capita emissions than New Hampshire at 18.8 metric tons, and all other states had lower per capita emissions than Vermont.

Authors Lena Stier and Jared Duval, who both work for the Energy Action Network, an organization that analyzes Vermont’s climate data, make the case for analyzing emissions through a per capita lens.

“If we accept that each state has a responsibility to reduce the pollution that they create — a responsibility, in other words, to do their fair share toward meeting science-based pollution-reduction targets — then per capita emissions become a very important basis of comparison across states to account for differences in population,” Jared Duval, executive director of the Energy Action Network, said at a webinar about the report on Wednesday.

Authors also found that Vermont has reduced climate emissions by only 11%, making it the Northeastern state that has made the least progress toward meeting the goals outlined in the Paris Climate Agreement.

The state’s per capita emissions are more than twice the global average, and cumulatively, it has produced more emissions than 70 countries across the globe, the report states. Still, Vermont’s emissions were about 20% lower than the average per capita emissions in the U.S.

In Vermont, the high per capita emissions compared to its neighbors seem to come from transportation, heating homes and agriculture. Together, transportation and thermal sectors account for 72% of Vermont’s emissions, “and per capita emissions in both of those sectors are among the highest in the region,” the report states.

Vermont has the second-lowest population density among the nine Northeastern states, and its sparse population and rural character require many people to use personal vehicles rather than less-polluting forms of transportation. Throughout the last two decades, Vermont has had one of the coldest winters in the region, causing a need for more heat. Many Vermonters use fossil fuels to heat their homes.

In the agriculture sector, Vermont has higher per capita emissions than any other Northeastern state, according to the report. While authors attribute the high emissions to methane releases from livestock, the agriculture data may not be entirely accurate, Duval said Wednesday.

The report’s authors used emissions data for Vermont from the Agency of Natural Resources’s emissions inventory, which has drawn information about emissions from federal agriculture standards. The agency is currently working with the Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets to make sure those methods accurately represent farming in Vermont, Duval said.

In the report’s introduction, authors address arguments often used to stop or prevent climate action from moving forward, which they said are “are often grounded in a belief that jurisdictions with comparatively low total emissions bear less responsibility than states or countries that have higher total emissions.”

Some also argue that climate action in a state as small as Vermont would be inconsequential, “justifying inaction with the assertion that our statewide emissions are too small to have any real impact in addressing the global climate problem,” authors wrote.

They argue that by looking at per capita emissions instead of total emissions, the comparison is more consistent.

“However, the fact that one state has fewer people than another does not absolve the smaller state from the responsibility to do its part to reduce the climate pollution that it creates,” the report states.