The University of Vermont and a proposed graduate student union have traded legal arguments at the state labor relations board, sparring over whether the union has the right to exist.

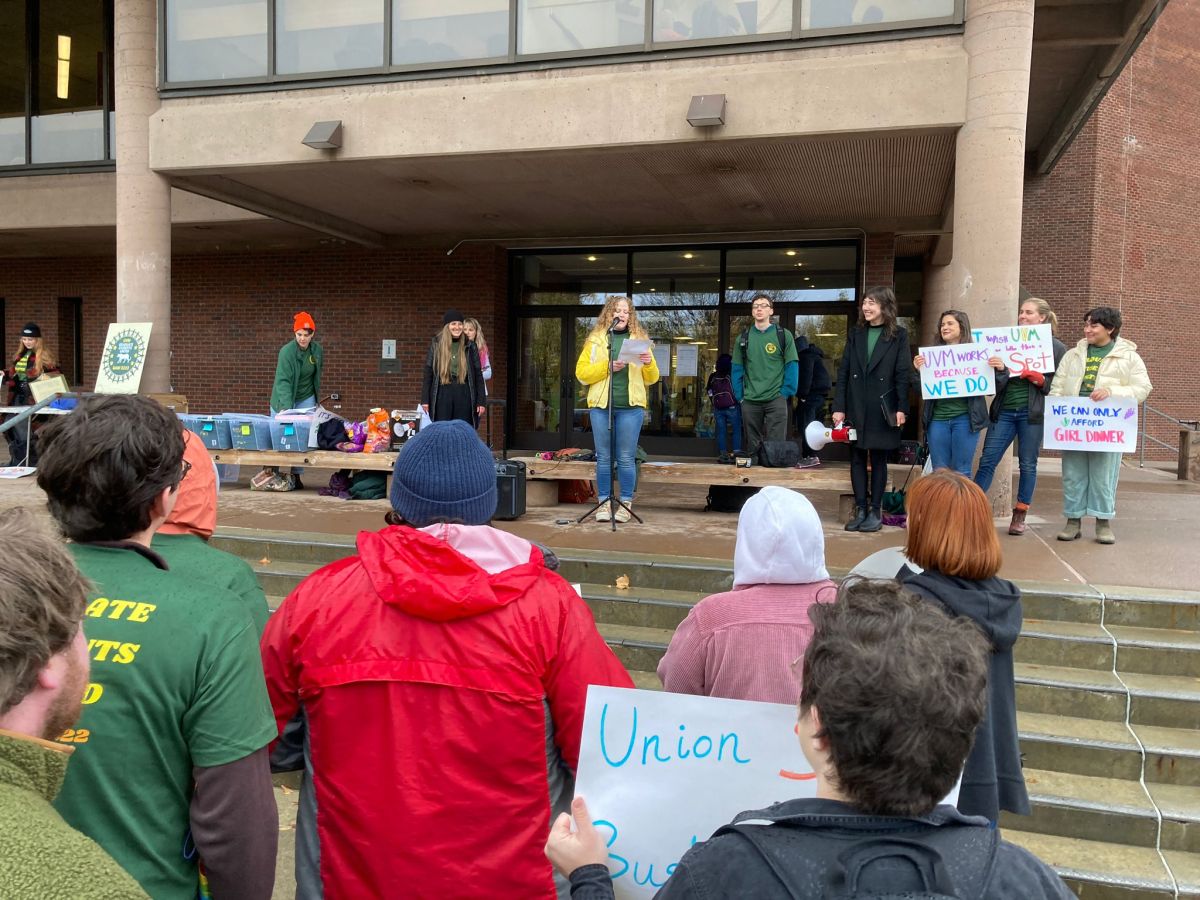

The back-and-forth comes as UVM graduate students are seeking to unionize in hopes of securing better wages and benefits. Last month, UVM graduate students petitioned the Vermont Labor Relations Board to become a union under the umbrella of the United Auto Workers.

The proposed union, Graduate Students United, would include an estimated 650 members, according to union leaders, including teaching assistants, research assistants and other graduate students who are employed in an academic field.

UVM opposes the effort. The Burlington university has emailed graduate students and posted a lengthy FAQ on its website outlining its concerns with the union drive.

In that FAQ, UVM noted that students “are free to sign a union card or you are free to choose not to sign such a card.”

But in a Nov. 8 filing with the Vermont Labor Relations Board, the university argued that the grad student union should legally not exist.

Attorneys for the university wrote in the filing that “none of the petitioned individuals have the right to unionize and the Petition should be dismissed.”

UVM “takes the primary position that all of the petitioned individuals are students and are not employees,” the attorneys, Meghan Siket and Nicholas DiGiovanni, wrote. Even if the labor relations board finds otherwise, “the Board should not exercise jurisdiction over them as it will potentially entangle the Board into graduate education at the University.”

In the event that the labor relations board found that Graduate Students United does have a right to unionize, UVM argued, the actual union should be smaller than the proposed one: It should exclude pre-doctoral trainees or fellows, graduate assistants who do not teach or conduct research, and other categories of graduate students. It’s not clear how many people fit into those categories.

Those arguments drew a sharp response from the union. In a Nov. 10 filing, an attorney for United Auto Workers said UVM’s claims rest on shaky legal ground.

In arguing that the union should not exist, UVM was contradicting both state law and “a tidal wave of contrary authority developed nationally and over the decades,” the attorney, James Shaw, wrote, pointing to over two dozen examples of graduate student unions across the U.S.

He also singled out the university’s claim that the labor relations board should not “entangle” itself with education at the university.

“The UAW is unaware of any basis for the (board) to decline to perform its statutory duties,” Shaw wrote. “In any event, this is just an old anti-union saw that universities have been saying for decades, but the fear has never materialized.”

If the parties cannot agree on the union’s composition, the labor relations board will decide after a hearing. After that, the union would hold an election among its proposed members.

In response to questions from VTDigger, Adam White, a spokesperson for UVM, said the university does not comment on ongoing legal matters. But the school “looks forward to presenting its evidence and argument to the Labor Board on this important issue of first impression in the coming weeks,” he said in an email.

Ayana Curran-Howes, a member of the Graduate Student Union’s organizing committee, told VTDigger in a text message that UVM’s argument was a “delay tactic” and “does not tread water.”

“We are interviewed, hired and fired, receive W2s, and gain ‘valuable professional experience in preparation for impactful careers’ just like every other employee ever,” Curran-Howes said, quoting the email sent by UVM administrators. “I would like to see how the administration thinks the University would run day to day without us??”