BURLINGTON — A Black student whose phone was bombarded by racist materials from a white supremacist group was told by school administrators to “wait for the next time” for action.

In Spanish class, when a white student asked if Latinas have “blood made out of guacamole,” the teacher looked at a Latina student and laughed.

An Asian student reported being asked, “If I put a piece of floss over your eyes, could you still see?”

These accounts of racism in Vermont schools come from a survey conducted by the Vermont Student Anti-Racism Network and its partners in the fight for racial justice in education.

“We believe that we all need to be part of the work to build anti-racist and equitable schools — everyone of all backgrounds and identities,” said Addie Lentzner, a student at Middlebury College who’s executive director of the student anti-racism network. “We hope this campaign will push more students and staff in schools to get involved in this important work.”

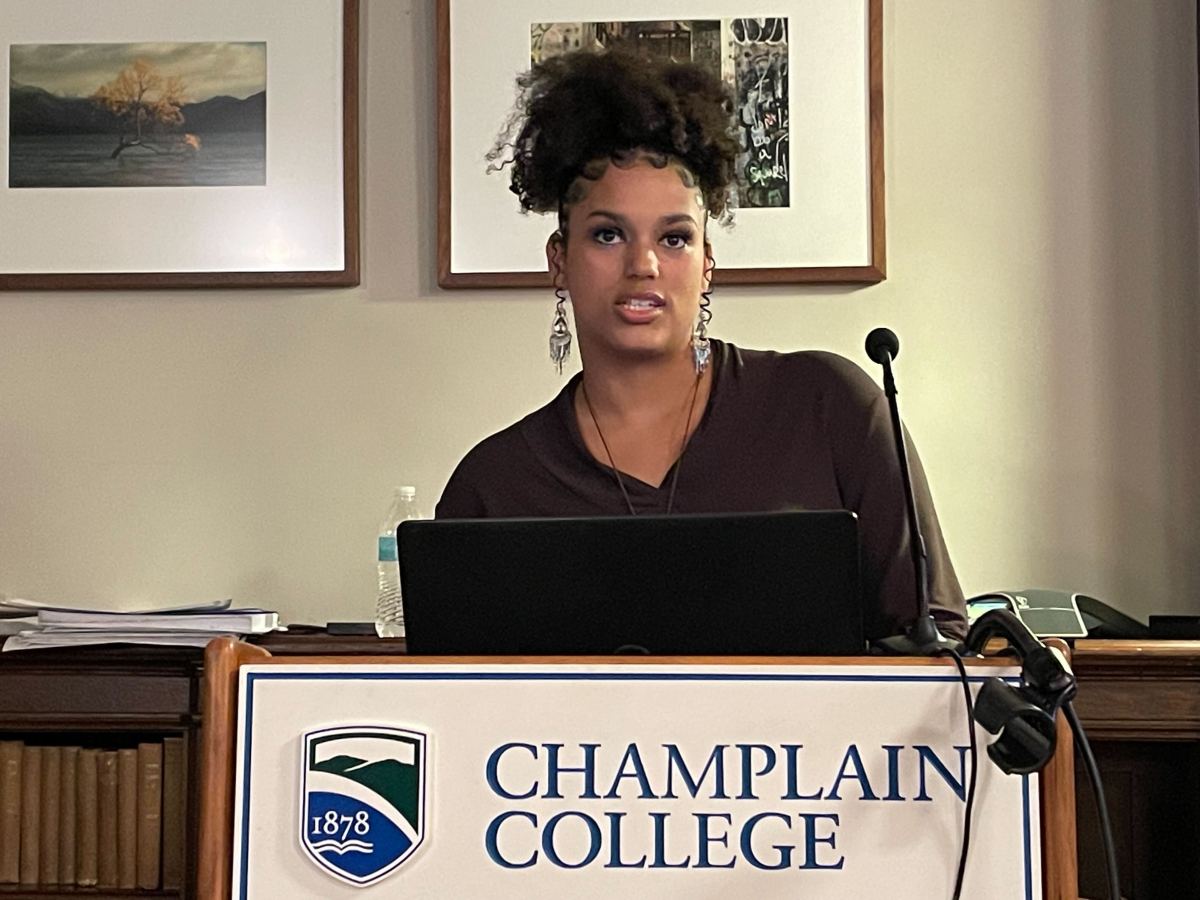

On Wednesday night, the student network and partner organization Rutland Area NAACP announced the Let Me Be Great campaign during an event at Champlain College’s Center for Community & Social Justice, attended by nearly 20 people and about 40 more online.

“In this campaign, we will tour Vermont schools and provide resources to students and staff, present survey results to school boards and administration, and more,” according to the campaign’s pledge signup, which asks youths and adults to “support and implement” the campaign’s components at their schools. “We firmly believe that students need to lead the charge to make change in our schools, which is what we’re doing with this campaign.”

The two-hour event included a remote speech by academic and activist Loretta J. Ross and a panel discussion by local students and activists working toward an anti-racist future.

Aaliyah Wilburn, a senior at North Country Union High School in Newport and a leader of the student anti-racism network, read a commentary she wrote about what racism feels like.

“The truth cannot be ignored,” she said. “Students of color are drowning in a sea filled with slurs, stereotypes, biases, and microaggressions. We gasp and wait for educators, administrators, and policy makers to care and help us. The helicopter might be in the sky but there is no ladder being put down to save us.”

She urged people of color to share their experiences, for white people to be allies in the work, and for educators and administrators to “put the ladder down and help us.”

Student advocates and their partners presented the findings from a survey launched this summer that catalyzed the Let Me Be Great campaign.

The survey was sent to 129 schools across Vermont, and only 11 sent replies, according to Gianni Solorzano of Building Fearless Futures, a Vermont nonprofit that brings anti-racist programming to schools and is a partner in the campaign.

Solorzano presented a qualitative analysis of the survey and said “the harm is rampant” and is affecting students and teachers of color across the state.

“Those seeking to cause harm are aware of how to do so without getting caught. So a lot of harm is occurring in what we’ll call a third space,” he said. These include bathrooms, school buses, hallways and social media.

Beyond BIPOC-targeted “jokes” and snubs in school hallways, Solorzano said, the survey points to teachers and administrators who look away, unwilling or unable to address instances of racism, or even are perpetrators themselves.

The survey also highlighted a wide gamut of responses — from students who say they don’t see racism to white students who see it and become frustrated when they are unable to help address the problem.

“It really shows us the long road that we have in regards to a more critical education, a more culturally inclusive education and deeper training for teachers to move towards an anti-racist pedagogy within all our classrooms,” Solorzano said.

The survey results include student suggestions such as, “Don’t have a no-bullying policy unless you are actually going to do something about it” and “We need a foundation of anti-racism counseling, and punishment.”

A panel discussion offered support and advice from four local racial justice advocates — Wilburn; Esther Charlestin, a former dean who left the Middlebury school district after facing racism and runs an equity consulting business called Conversation Compass; the Rev. Mark Hughes, executive director of the Vermont Racial Justice Alliance and co-chair of the state Health Equity Advisory Commission; and Netdahe Stoddard, an anti-racist activist with Building Fearless Futures.

“This is not a project, this is not a program and this is not a campaign. This is a lifestyle,” Hughes said of his experience of working for racial justice. “So when we make a decision to go on this path, we change the way we live. It’s a belief system.”

“We need to do better for our kids. We need to do better for our future. And I think having all of you here today virtually and in person is a great step towards that,” said Mia Schultz, president of the Rutland Area NAACP, who joined remotely. She said her organization has seen an uptick in complaints about racism, with no pathways to finding solutions through school administrators.

In the coming months, the Vermont Student Anti-Racism Network plans to visit schools, conduct workshops and provide resources to faculty and youth about racial justice in schools.

“We’ve already gotten requests from a couple schools who want presentations, and many more are signing the pledge,” said Lentzner, who started the student anti-racism network when she was attending high school remotely during the Covid-19 pandemic.