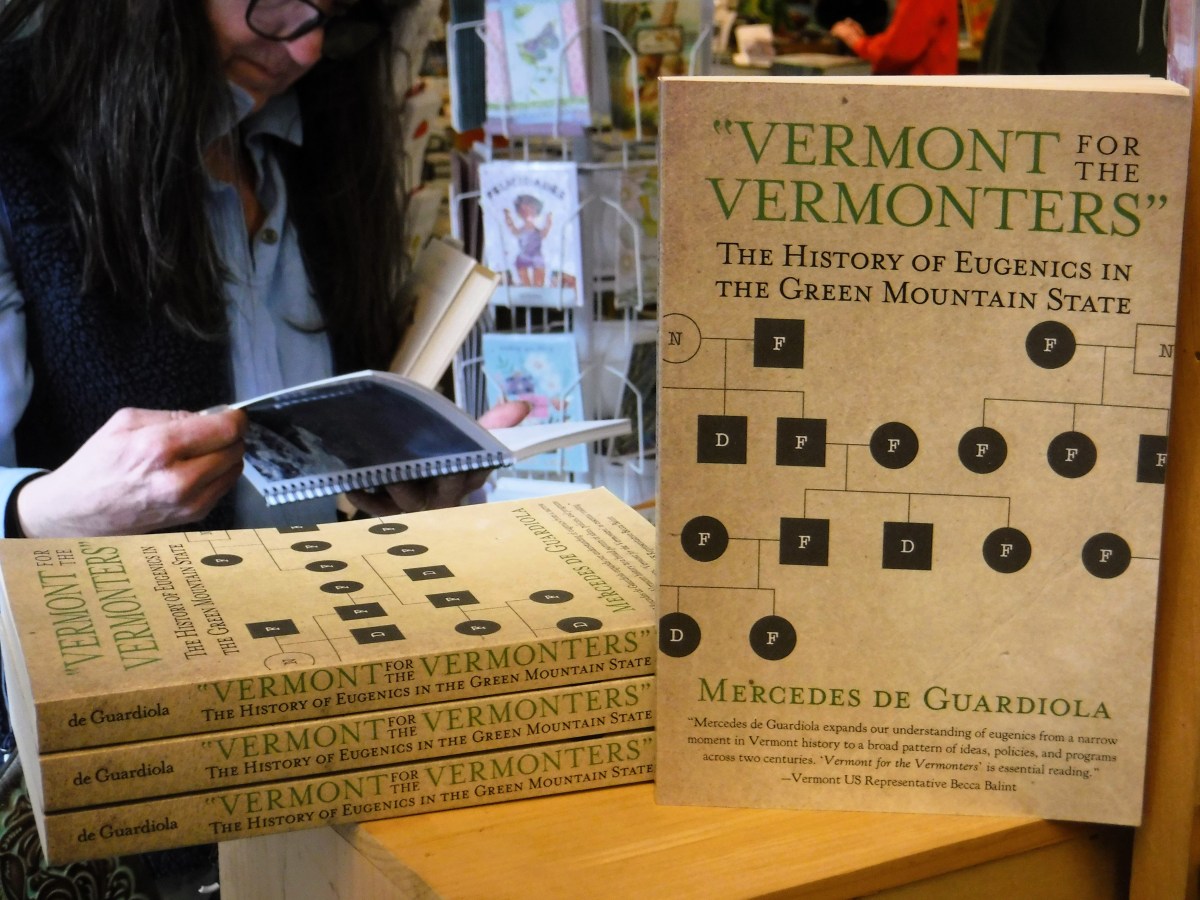

When Mercedes de Guardiola tells people about her new book “‘Vermont for the Vermonters’: The History of Eugenics in the Green Mountain State,” she often has to explain that the subject refers to a century-old pseudoscientific campaign for selective human breeding.

But that answer only sparks more questions.

Many Vermonters don’t know the state was one of many in the early 1900s that aimed to reduce such perceived problems as “feeblemindedness” and “degeneracy” by targeting certain populations for family separation, institutionalization and permanent birth control measures, including tubal blocks and vasectomies.

“The story of eugenics in Vermont often goes as follows,” de Guardiola begins her book. “In 1925, University of Vermont professor Henry F. Perkins founded the Eugenics Survey of Vermont to carry out investigations into Vermont families and advocate for eugenical public policies. The private organization successfully lobbied for the legalization of voluntary sterilization in 1931 and closed in 1936, leaving eugenics to slowly die out in the state.”

But de Guardiola knows the reality was “far more lengthy and complex,” especially for those targeted. A 2017 graduate of Dartmouth College, she researched the topic for a prize-winning thesis before publishing her findings in a scholarly journal and her 238-page history.

“One thing I heard when I was pitching the book was, ‘What is the relevance today?’” she said in a recent interview.

At a time of increasing headlines about mental health, substance use disorders and homelessness, de Guardiola has a ready answer.

“It’s about what happens when state systems of social support collapse and how people respond,” she said. “And that’s a story that’s familiar to us now.”

De Guardiola has teamed with the Vermont Historical Society to publish her book and is set to present a public virtual program this Thursday.

“Despite growing scholarship, we continue to have limited knowledge about the extent of eugenics,” writes de Guardiola, who testified before the state Legislature in 2021 when it formally apologized for past practices. “Forgetting or ignoring eugenics further allows eugenicists’ work to fester by precluding any attempt to address its impact.”

The author first learned about the topic through fellow historian Nancy Gallagher’s 1999 “Breeding Better Vermonters: The Eugenics Project in the Green Mountain State,” which focused on Perkins and his work.

“It became apparent,” de Guardiola recalled, “there was more to say about the broader history of why and how eugenics emerged in Vermont.”

The new book opens with then-Gov. John Mead using his 1912 farewell address to warn of a rise in “degenerates” and “defectives” who, he argued, were draining local and state services with “little or no hope of permanent recovery.”

Mead proposed three courses of action: “1. Restrictive legislation in regard to marriages. 2. Segregation of defectives. 3. A surgical operation known as vasectomy.”

Such suggestions would shock today. But a century ago, many Vermonters — seeing public welfare systems overwhelmed and underfunded after a flu epidemic in 1918 and a statewide flood in 1927 — viewed the steps as a potential “humane solution,” de Guardiola learned.

As the Roaring ’20s gave way to the Great Depression, Perkins established the Eugenics Survey of Vermont.

“Will the breeding stock of the future be as virile as it has been?” the University of Vermont professor asked in 1930. “If not, is the seed deteriorating in quality or are Vermonters neglecting to keep the soil of their seed-bed — the physical and social environment of their children — rich, mellow and weed-free?”

State leaders debated and defeated bills on the topic in 1912 and 1927 before passing “An Act for Human Betterment by Voluntary Sterilization” in 1931.

The new book details the rise and fall of the state’s eugenics movement through public and private records and reports. Researching reams of paperwork, de Guardiola found one thing lacking.

“Victims’ voices are the one area that’s missing,” she said. “These were people’s friends, family and neighbors. What was it like to be locked up in an institution? What were the results of marriage restrictions? Sterilization?”

The new book is the latest in a Vermont Historical Society series on such pertinent subjects as “Discovering Black Vermont: African American Farmers in Hinesburg, 1790-1890” by Elise Guyette and “Repeopling Vermont: The Paradox of Development in the Twentieth Century” by Paul Searls.

“Though emotionally challenging,” society head Steve Perkins said of the eugenics title, “the story is a must-read for anyone looking to understand community, exclusion and belonging.”

The book comes as the state is forming a truth and reconciliation commission to address “institutional, structural and systemic discrimination” past and present caused by state policies, according to a new law.

“There’s still a lot that we don’t know,” de Guardiola said. “This history can hopefully help us understand what has and hasn’t worked in the past and build a brighter future.”