This Then Again column was first published in 2017.

Looking back at Cyrus Pringle’s ancestry, it seems only natural he would become a horticulturist. That he would also become a great botanist — one of the most important this nation has produced—is more surprising.

Pringle’s love of the plant world seems to have grown out of his ancestors’ experiences and his own childhood in Vermont. Born in 1838 in East Charlotte, Pringle once wrote that, in his choice of professions, he had been “(p)rompted by the same taste which led my grandfather to plant a nursery of fruit-trees amid the early wilds of Vermont … and by the same spirit that made my father, in later years, going over some of these orchards, change by his skill the smaller and harsher kinds of fruit for the more perfect and beautiful sorts…[.]”

Pringle’s career, which for decades carried him across the United States and down into Mexico in search of new species, started on the family’s Charlotte farm in 1857. By the time he was 19, he was hybridizing apple trees.

“I have sought to surround myself with fruits,” he later wrote. He found in horticulture “employment for my hands, recreation for my … body and relaxation and diversion for my mind.”

The next year, he plotted out a small nursery that included a pear orchard and gardens for growing cherries, currants, grapes, peaches and potatoes.

He took time away from the garden in 1859, when he enrolled at the University of Vermont. But his formal education was short-lived. His older brother died during Pringle’s first semester at UVM and he was obliged to return to help his already widowed mother tend the farm.

Pringle’s service to his mother was preempted in 1863 when he was drafted to serve in the Union Army during the Civil War. As a young man, Pringle had been drawn to the teachings of the Quakers and, several months before getting drafted, had married an ardent Quaker, Almira Greene of Starksboro. Following the Quakers’ principle of pacifism, Pringle refused to have anything to do with the war. He wouldn’t carry a gun, work in a military hospital, or even pay a “commutation fee” to get out of serving.

For his tenacious commitment to his beliefs, he was treated with occasional cruelty and brutality. At one point, Pringle was stretched out and staked under a blazing midday sun in Virginia and left there until he was greatly weakened and almost delirious from sunstroke. Pringle remained a prisoner until President Lincoln intervened out of respect for the Quakers’ nonviolent ideals.

Returning to Vermont, and to his wife and mother, Pringle threw himself back into horticulture. He worked to create new varieties of corn, currants, grapes, plums and tomatoes. He produced a new potato variety he named “Snowflake.” A pair of New York City brothers purchased the rights to the variety in exchange for 55 percent of their sales. Pringle created other varieties of potatoes, and of wheat, flowers and squash, for his business partners.

His work earned him awards from horticultural societies in Massachusetts and across the ocean in London. But, while his professional life bloomed, his marriage withered. Cyrus and Almira separated in 1872 and eventually divorced. Almira got custody of their child, Annie.

Some historians blame the divorce on Almira’s desire to preach her religion, or alternately on her ill health, but scholar Kevin Dann in his 2001 book “Lewis Creek Lost and Found” writes that the cause was Cyrus’ dedication to a particularly ill-paying profession. Pringle’s business deals had produced moderate fame in certain circles, but apparently not much fortune.

Around the time his marriage was dissolving, Pringle shifted his focus from propagating new plants to collecting samples of those that existed in nature. His knowledge of botany and his dedication to the field became known throughout the region.

In 1872, George Davenport of Medford, Massachusetts, a leading fern expert, asked Pringle to search for a variety of fern species in Vermont. Pringle, who had never previously collected ferns, proceeded to gather all but four of the state’s species. Other botanists contacted Pringle and asked him to collect fungi and lichen.

Pringle began traveling to remote parts of Vermont to catalog the variety of plant life in his native state. He made pilgrimages to the cliffs above Lake Willoughby and to Camel’s Hump, but soon found more diversity on Mount Mansfield.

Pringle wrote a paper on the grasses of Vermont, which he illustrated with 60 specimens. He prepared a display on the plant life of Vermont for the Paris Exhibition of 1878, which also featured Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone.

Pringle’s work came to the attention of Professor Asa Gray of Harvard, then the nation’s leading botanist. Gray, as well as officials with the Smithsonian Institution and other museums, recognized Pringle’s passion and his genius, and began hiring him to make distant botanizing journeys.

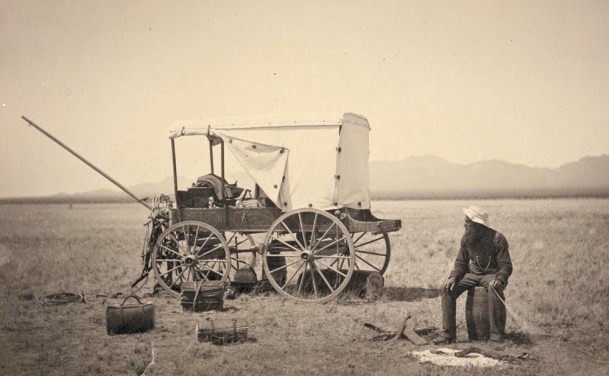

For four years, beginning in 1880, he traveled to California and the Southwest to make general collections for Gray, to collect wood specimens to complete an important collection at the American Museum of Natural History, and to collect information on the region’s forests for the U.S. Census Department. Then the Smithsonian hired him to work on a botanical survey of Arizona.

The following year, in 1885, Gray hired Pringle as a botanical collector for Harvard’s Gray Herbarium. Gray dispatched Pringle to Mexico, where he began a series of exhaustive and groundbreaking explorations that would span 26 years.

“My own troubles, during my first years here and the several failures of healthy young men coming here with me, may give you a hint — a slight hint — of the difficulty of living and traveling in this country and carrying on the work which I have undertaken,” he wrote. “The long marches under a tropical sun (one burdened with his necessary outfit of food water, etc., and with his increasing collections), the laborious climbing and clambering over terrific, often perilous mountains, the patient undefatiguable (sic) gleaning after rare plants growing scattered, the obstacles interposed by the storms, peculiar to these regions, sometimes by wild beasts and rarely by the inhabitants of the country — all these difficulties are forgotten, when the collector gets home at the end of the year with his stores of booty, but they rise in his way as he enters his field again.”

Pringle’s life must have been a constant cycle between the dread of the tough road ahead and the thrills of the discoveries he would make. During one four-year stretch, Pringle traveled 56,000 miles, which included his journeys between Charlotte and Mexico and his wanderings within Mexico.

Pringle would arrive home in Vermont from one of his expeditions with trunks and boxes full of specimens he had pressed in the field. He would mount and sort the specimens and ship them off to various botanists for formal identification. He shipped specimens to Harvard and the Smithsonian Institute, and museums in Great Britain, Austria, Germany, India and Australia.

Pringle had a prodigious memory for plants. As his colleague O.W. Barrett recalled, “He liked to boast — his only jest of this sort — that he could call over 10,000 plant acquaintances, and a few botanical friends, by their proper names — though he was not certain as to who the president in Washington might happen to be.”

Pringle spent 35 years working in the field in the United States, Mexico and Canada. He learned from Gray that if he had multiple specimens of a rare species, he could trade them to other collectors for other wondrous examples of plant life.

Pringle proved invaluable to the world’s botanical collectors. During his career, he shipped more than 500,000 plant specimens to collecting institutions. Those shipments comprised roughly 20,000 species, of which an estimated 12 percent were new to science.

Through his specimen trading, Pringle was able to assemble an impressive personal collection. In 1902, the University of Vermont acquired Pringle’s collection and hired him to oversee it, which he did until his death in 1911.

Today, the great botanist’s collection still forms the backbone of UVM’s famed Pringle Herbarium, which is the third-largest in New England. (Its holdings also include an earlier collection created by Fanny Penniman, widow of Ethan Allen.)

More recently, Pringle was honored by the Red Hen Baking Co. of Middlesex, which introduced its Cyrus Pringle Bread. Appropriately, the bread was made entirely from wheat that was grown, like Pringle’s own interest in plants, right here in Vermont. (Cyrus Pringle Bread was phased out in 2022.)