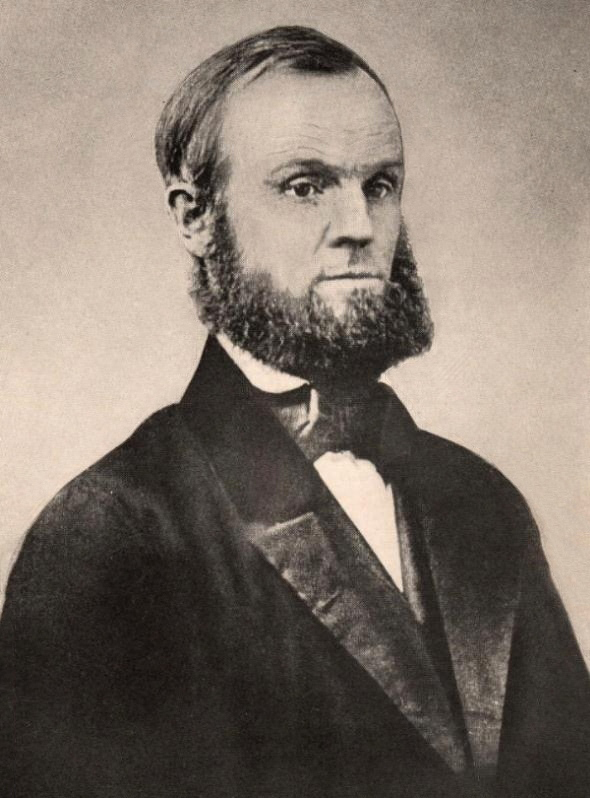

John Humphrey Noyes’ life was a jumble of contradictions. Here was a pathologically shy young man living in the prudish Victorian era, whose main claim to fame was starting a society that included the free exchange of sexual partners. And his justification for creating this polyamorous community was religious.

Nothing about his family circumstances hinted that his life would follow this path. Noyes was born into a large and prominent Brattleboro family in 1811. His father was well known in town, being a successful businessman who once represented Vermont in Congress. His mother’s side of the family would one day produce a U.S. president, Rutherford B. Hayes.

Noyes’ most distinguishing trait was his paralyzing shyness when meeting women. Some commentators have argued that Noyes’ shyness was inherited — he was supposedly descended from a line of shy men, who either married late or chose to marry cousins because they feared courting so much. In truth, it wasn’t uncommon for cousins to marry at the time, since it wasn’t yet taboo or known to be a risk to offspring.

Whatever the cause of Noyes’ bashfulness, he described its intensity this way: “I fully believe that I could face a battery of cannon with less trepidation than I could a room full of ladies with whom I was unacquainted.”

Instead of courting, Noyes focused his energies on his professional life. He had originally wanted to become a lawyer, but his plans changed in 1831 when he had a conversion experience while attending an evangelical revival meeting in Putney, which is just north of Brattleboro. Noyes enrolled at the Andover Theological Seminary before transferring to Yale Divinity School, where he was said to study 12 to 16 hours a day. While at Yale, he adopted the unorthodox Christian doctrine of Perfectionism.

While mainstream Christian doctrine assumed that Christ’s return would coincide with the Day of Judgment, Noyes and other Perfectionists argued that the Bible had been misinterpreted and that Christ had already returned during the lives of the Apostles. Therefore, they argued, the Millennium (the 1,000-year period that would start with Christ’s Second Coming) had long since passed, so Christians could now attain the state of perfect holiness promised in the testimony of John and Paul.

In his unique interpretation, Noyes believed that people didn’t achieve perfection through deeds, but rather through their attitude, especially their inner confidence that they had been saved from sin. Thus, he believed he had already attained salvation.

Yale, which had been founded to train Congregationalist ministers, granted Noyes a preaching license in 1833 and he was assigned to a small parish outside Albany, New York. But, just months later, when Yale got wind that Noyes was preaching his unconventional beliefs, the college revoked his license and expelled him.

Noyes’ life spiraled out of control. He traveled to New York City and suffered some sort of mental breakdown, drinking heavily and wandering the streets all night. Hearing reports of his behavior, his family sent a friend to retrieve Noyes and bring him back to Putney.

An $80 ‘love token’

Surrounded by family and friends, Noyes swiftly improved and he began to form a community of Perfectionists, starting with his siblings. Gradually, he began to attract followers outside his family.

One of those converts was a wealthy woman named Harriet Holton, who was enthralled by his preaching and sent him $80 as a “love token.” Noyes and Holton married in 1838. This might not have been a true love match — Noyes was infatuated with other followers. But Holton’s wealth helped alleviate Noyes’ concerns about how he was going to make a living.

Noyes wanted his Perfectionist society to adopt something he called Bible Communism, which required the sharing of all property and profit from the community’s endeavors.

The sharing didn’t end there. Community members would gather regularly in small groups to conduct “mutual criticism” in which the failings of each would be discussed to set them on the road to perfection.

Most controversial, however, was yet another kind of sharing, a doctrine that Noyes called “complex marriage.” Some of his Putney neighbors disparaged it as “free love.”

Under complex marriage, all the community’s women were considered married to all the men, and vice versa. Noyes argued that traditional marriage of one man and one woman was contrary to Bible teachings and promoted the vices of jealousy and selfishness. Exclusive relationships were not permitted and any couples that seemed to be growing too close were separated.

Noyes also wanted to free women from the pain, and occasional anguish, of frequent childbirth. His wife, Harriet, had endured five painful pregnancies in six years, and yet only one baby had survived childbirth.

To reduce the number of pregnancies, Noyes promoted a birth-control technique he called “male continence” or coitus reservatus. While Shakers’ abstinence required resolve, Noyes argued that male continence required the same “power of moral restraint.” That “self-control,” he explained in the euphemism-laced language of the Victorian era, was needed “after the sexes have come together in social effusion, and before they have reached the propagative crisis.” The technique put more emphasis on the woman’s pleasure than the man’s, and Noyes reported a happy side-effect: “My wife’s experience was very satisfactory, as it had never been before.”

Breaking the bonds of traditional marriage and inducing fewer pregnancies would help the group, Noyes believed, by allowing men and women to work side by side in community businesses. He saw it as a mutually beneficial trade-off. It would reduce the burdens on women in the household and men in the workplace. “Men and women will mingle like boys and girls in their employment,” Noyes enthused, “and labor will become sport.”

Between 1838 and 1847, Noyes drew a few dozen followers and organized them as the Putney Corporation or the Association of Perfectionists.

But all was not well. When details of the group’s unorthodox social arrangements emerged, scandalized neighbors told the county sheriff what they knew, and he soon arrested Noyes for adultery and adulterous fornication.

His brother-in-law posted bond, but Noyes was not interested in having his day in court. He and other leaders of the corporation left town for New York State in 1847. “We left not to escape the law,” Noyes said later, “but to prevent an outbreak of lynch law among the barbarians of Putney.”

Building community in Oneida

With his Putney followers, Noyes resettled in Oneida, New York, and quickly found new converts. By 1851, the Oneida Community, as it became known, had 205 members. It would peak two decades later at more than 300 members.

A photograph of the Oneida Community shows a group of men and women clustered outside around tea tables. It could be any Victorian tea party, except that the women all have short hair, a style Noyes recommended to break down distinctions between the sexes. And the women are wearing trousers, though they are wearing mid-length skirts over them, perhaps as a last vestige of gender-specific clothing.

Behind the tea drinkers in the photo rises the mansion that was their home and a testament to their success as manufacturers of animal traps, chains, silk threads and other items. The Community didn’t turn a profit until 1857, but after that the business grew steadily.

Despite the Community’s unusual social arrangements, visitors said it had none of the outward signs of a sexually charged environment. Indeed, any public displays of courting or physical affection were shunned. Rendezvouses were arranged discreetly, usually by the men, who would pass a note to their love interest via a trusted female friend.

To prevent older members of the community from being excluded from these liaisons, Noyes instituted a system where members were ranked based on their level of spiritual attainment. People who were ranked lower on the scale were encouraged to associate with higher-ranked community members in order to improve their spirituality.

Despite the strict application of birth control, the community did produce children. One study found that during a 20-year period (1848-1868), the community had 12 unplanned births. Most births, however, were carefully planned — too carefully planned.

In addition to all the other controversial experiments Noyes encouraged, he also dabbled in eugenics. Though everyone in the Community was supposedly equal, some were treated as more equal than others. Working with a committee, Noyes identified traits he admired in some community members and arranged for them to procreate. Women, however, were allowed to decide whether they wanted to have babies.

Mothers and fathers were discouraged from forming tight bonds with their children, who were instead raised communally and lived separately from their parents.

A turn toward business

The 1870s brought hard times. Area preachers used their sermons to attack the Community, which was already in a succession battle over who would lead the group after Noyes’ death.

In 1879, when a confidante informed Noyes that local authorities were about to arrest him for statutory rape, he fled to Canada. Noyes would remain there for the last seven years of his life. In his absence, community members decided to reject the idea of complex marriage and adopt the mores of the outside world.

In 1880, community members committed their last heresy against Noyes; they dropped the last remnant of their communist ways and transformed their business into a joint-stock corporation. Today the name Oneida is still prominent in the glassware and silverware markets.

Late in life, reflecting on his social and religious experiment, Noyes saw nothing but success. He said: “We made a raid into an unknown country, charted it, and returned without the loss of a single man, woman, or child.”