BENNINGTON — In early July, Cindy Thomson learned that the water in her well contained industrial chemicals that have been linked to health problems.

That discovery led state inspectors to test more private wells in Bennington, and they found that the drinking water for at least a dozen households contained PFAS levels beyond the state’s safety limit.

The news came a year after Saint-Gobain Performance Plastics settled a 2016 class-action suit brought by Bennington-area residents who alleged that the company’s local factories had tainted their soil and water with a type of PFAS. Those residents are receiving financial compensation and/or medical monitoring, and many have since been connected to municipal water or water treatment systems.

The wells that recently showed significant levels of the chemical contaminants were not covered by the lawsuit settlement, because they’re outside the established “zone of concern.” They’re located south of Vermont Route 9, while the case involved only those north of the highway.

Thomson’s well has now been tested three times for the presence of PFAS — perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, which have about 15,000 variations used in a wide range of consumer products. Her water results included 22.1 and 31.2 parts per trillion of PFAS — exceeding Vermont’s legal limit of 20 parts per trillion for five specific variations.

Some people may have thought the PFAS chapter in the town’s history was coming to a close, but not Thomson.

“It’s one of those things where it just doesn’t surprise you,” she said.

Thomson, 71, moved to Bennington when she was 10 and grew up at a time when manufacturing dominated the local economy. Thomson said she remembers during the early 1970s, while she was in college and working as a town pool lifeguard, a “horrendous” smell would emanate several times a week from a factory across the street. It was one of two ChemFab facilities in Bennington that Saint-Gobain, a French multinational corporation, would later acquire.

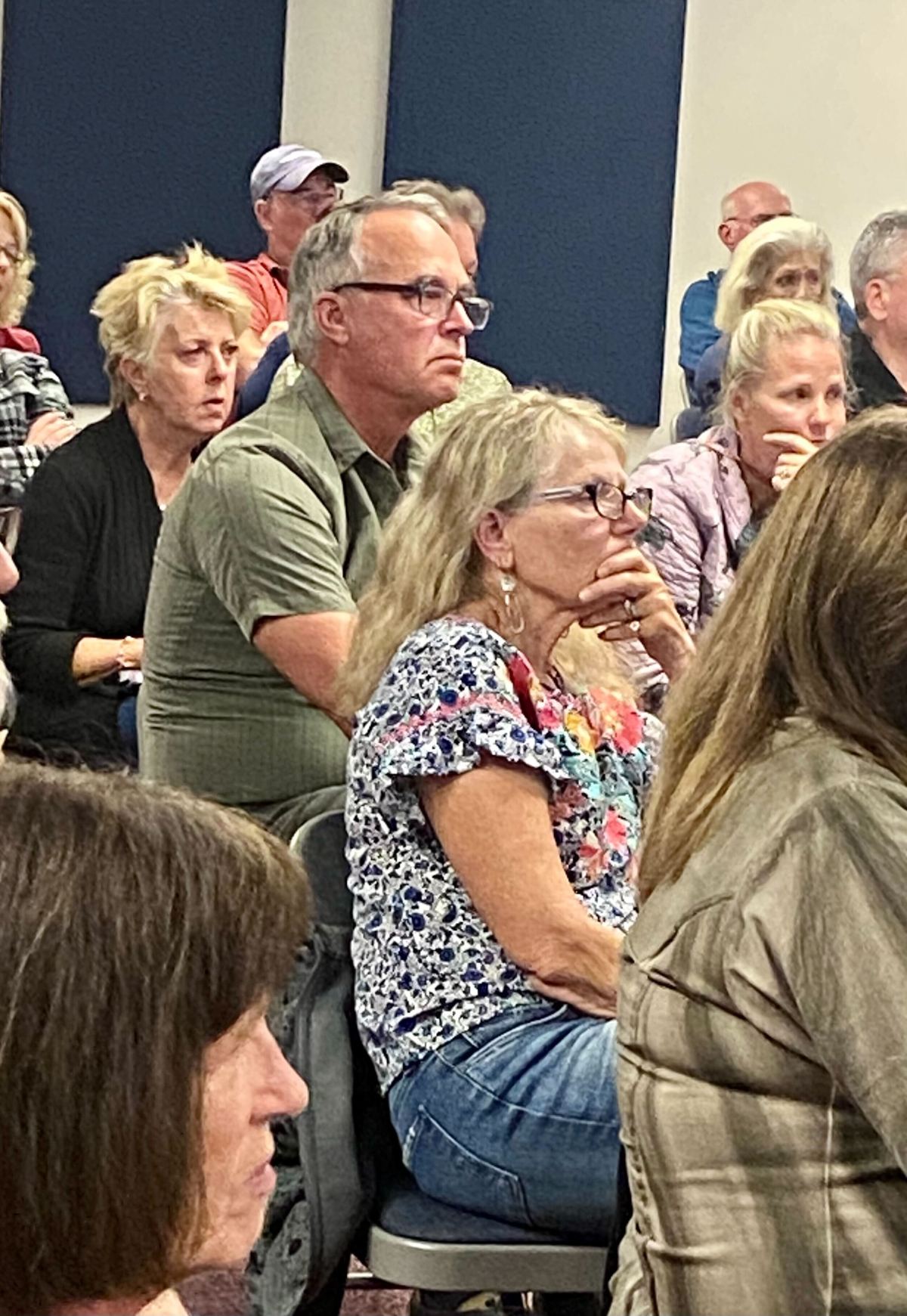

At a public meeting in Bennington on Thursday evening, which drew about 65 people, some residents voiced concerns that their drinking water contained PFAS.

One person asked why the newly affected homeowners haven’t been added to the list of beneficiaries in the class-action suit against Saint-Gobain.

Richard Spiese, an environmental analyst at the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, said he did not yet have the data to determine who might be responsible for the recently discovered water contamination. He said it could be Saint-Gobain, a different entity altogether or a combination of sources.

“I’m the water detective,” said Spiese, who is part of the team that has been testing for PFAS in Bennington water wells since 2016. “Until I’m convinced, and I can convince my boss and probably convince her boss, we’re not going to file a suit against Saint-Gobain.”

Among the reasons, he explained, was that the new group of wells showed PFAS variations that hadn’t been detected in the wells involved in the Saint-Gobain lawsuit. He said there are other potential sources of the chemicals in the affected area, including landfills and old manufacturing facilities.

Some residents wanted to know whether there was a process that could remove PFAS from the human body, or if the state would ask residents to undergo blood tests.

Dr. Sarah Owen, the state toxicologist, said health officials don’t recommend blood testing because PFAS are so pervasive that the substances are in everyone’s body. If people stop drinking PFAS-tainted water, she said, their levels would go down over time, but they can never be completely purged.

“One of the reasons that PFAS are so toxic is that they don’t leave our bodies,” Owen said of the substances dubbed “forever chemicals.”

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, some studies have shown that exposure to certain levels of PFAS may harm human health. These potential adverse effects include higher risk of some cancers, decreased fertility, weaker immune system and development delays in children.

To mitigate the drinking water contamination, the state government has already started distributing bottled water to affected homes. The next step, he said, is to provide in-house water treatment systems to those whose PFAS levels are above the state safety limit.

The long-term plan is to give affected homes the option to connect to the Bennington municipal water system, which officials said has non-detectable levels of PFAS.

“We have the capacity to serve more people,” said Bennington Town Manager Stuart Hurd. The issue, he said, is whether the water can reach all the locations. “Whether or not we can get it to you is an engineering question.”

He said the municipal government will be looking for funding to extend the town water system to affected residents.

Thomson, who attended the meeting with her husband, George Schmidt, told VTDigger she was disheartened to be facing this water problem. But at the same time, the retired teacher feels fortunate not to have experienced any major health problems.

“The way I feel is that I dodged another bullet,” she said.