RUTLAND — Jeff Dejarnette started his company last year after a mentor, Kalow Technologies founder Rick Gile, introduced him to his granddaughter-in-law, a traveling nurse.

She told him about some of the training challenges traveling nurses face. That’s when he first learned about a code cart, a piece of equipment introduced in the most vital moments of a patient’s hospitalization.

The code cart, also known as a crash cart, is wheeled into an emergency room to save a patient’s life. It contains instruments for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and other medical supplies. The carts enable medical personnel to save time in an emergency, thereby increasing the chance of saving a patient’s life.

However, each hospital configures the carts in a different way, which means that every time traveling nurses arrive at a new hospital, they need to learn the new configuration, Dejarnette said.

“There’s no standardization,” he said. “And there’s different types of code carts, like adult, neonatal, pediatric, so that makes it harder to learn them.”

Dejarnette believes his device could save lives in “code blue” situations — the term for medical emergencies. He cited research that found that 200,000 cardiac arrests occur in U.S. hospitals every year, and nearly 80% of those patients do not survive.

“If we could get people familiar, especially with code blue situations, and train in a comfortable environment, then they’ll be more prepared,” he said. “They’d be less likely to make medication errors.”

If virtual training on crash carts could reduce cardiac arrest deaths by 5%, he estimated that 10,000 lives a year could be saved in the United States.

Stephanie Wilbur, assistant professor of nursing at Vermont State University Castleton, said each unit in a hospital has different needs for its crash cart.

The real-world carts are expensive, and training on one makes it unavailable for use with patients. Wilbur said nursing students must wait until a real code cart is opened before they can dig through it.

“Once it’s open, it has to go through all these different checks and closure procedures,” Wilbur said. “So it’s kind of a big deal to open up a crash cart because we need to make sure that everything’s back in the right place when we close it back up again.”

Dejarnette thought a virtual crash cart could solve this problem.

Pitching the idea to hospitals

Over the next week, he said, he developed a prototype of a crash cart on virtual reality goggles. He decided to name his company Tacitly, as tacit knowledge is something gained through hands-on interactive learning. He saw that the domain name tacitly.com was available for $4,000.

He kept testing the software with health care professionals, refining the software in his room at his house in Rutland.

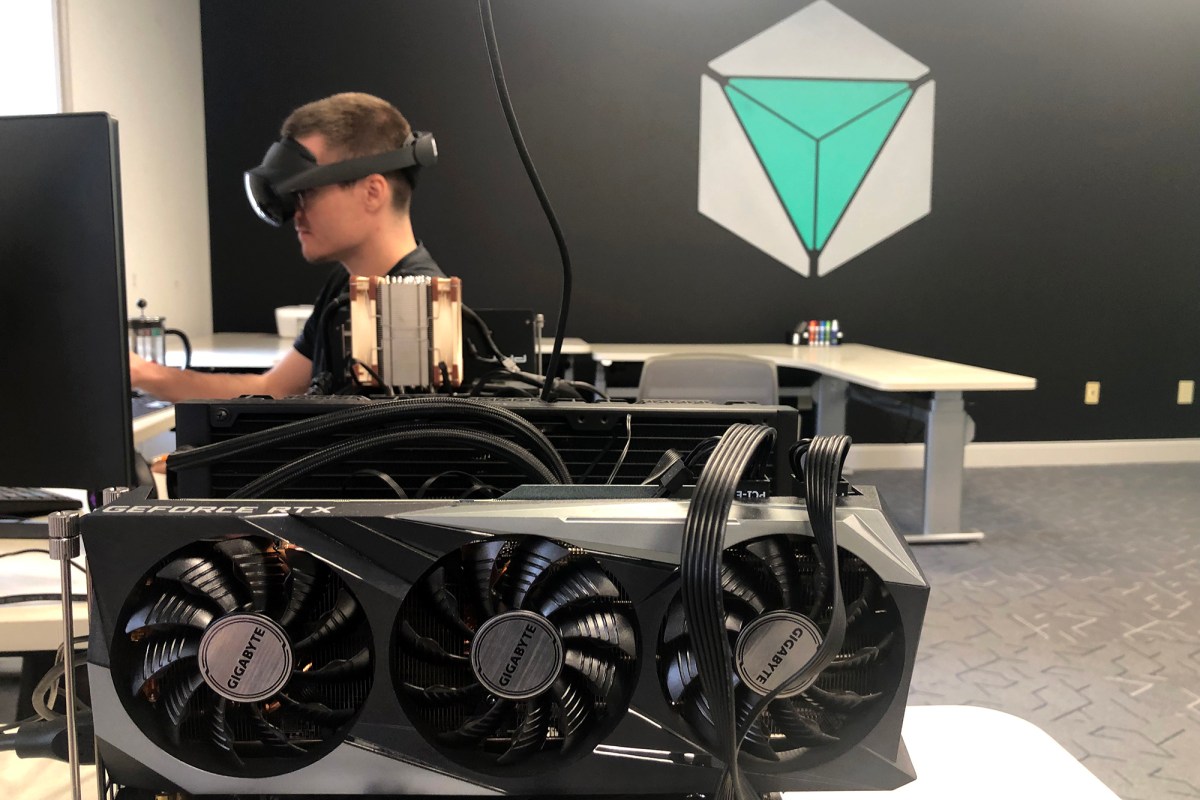

Eventually, Dejarnette rented an office at The Hub CoWorks, a space in downtown Rutland. He hired a couple of interns from Castleton University, which is now part of Vermont State University. Later on, he hired two full-time software developers.

They ran a three-dimensional scan of Rutland Regional Medical Center’s code cart and began getting their foot in the door with other hospitals to learn more about code carts.

They made digital twins of code carts at The University of Vermont Medical Center and Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center. He hopes to work with both medical centers as customers. Eventually, Dejarnette said, he would like to target the largest health care networks in the country.

His biggest challenge, he said, is to get hospitals to adopt the technology because it is so new.

“There’s just so many decision-makers in a hospital,” Dejarnette said. “They’re all enthusiastic, and they all love it — the people who have seen it — but then you have to convince their boss, and then they have to convince their boss.”

He said Tacitly tested its virtual crash cart with nurses and nursing students, including at UVM Medical Center, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Rutland Regional Medical Center and Castleton, where 30 nursing students tested the digital code carts.

“I’m thrilled to see a Vermont company developing in the extended reality field,” said Rajan Chawla, faculty technology liaison at Larner College of Medicine Technology Services at The University of Vermont.

Part of LaunchVT

After Dejarnette founded the company, he persuaded a friend, Bill Kuker, who co-founded Martello Technologies, to become a co-founder.

Tacitly occupies a big space, most of which is still empty, at the Hub CoWorks office space. Dejarnette looks forward to hiring more people once he lands his first customer. He hopes to convert the Hub into a hub for extended reality startups.

On a wall is a blown-up drawing of Dejarnette’s first patent, which had nothing to do with extended reality. It depicts a fishing hook designed to release a fish without touching it. He used the money from the sale of that patent to start Tacitly.

Tacitly was one of eight startups in this year’s cohort of LaunchVT, the Lake Champlain Chamber’s business accelerator, which included startups from all over Vermont. Dejarnette called it “a great learning experience.”

LaunchVt pairs entrepreneurs with mentors. Dejarnette’s mentors were Jeff Chu, an investor in medical technology, and Brady Hoffman, life science program director at viz.ai.

“What I learned the most was about raising capital,” he said.

Eventually, Dejarnette said, he would like to expand into other virtual devices, such as defibrillators as well as X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging devices.

“We hope that we can build something that is going to create a lot of good jobs and be cool,” he said.