Franklin County Sheriff John Grismore was eager to talk about the possibility of his own impeachment on a recent morning as he sped down Route 105 in his cruiser, scanning the road for a car that he and his deputies worried had a young girl inside with a knife.

“It certainly stinks of a witch hunt,” Grismore told a reporter, speaking about the Vermont House probe that started in May and is set to run deep into the fall, at least. Over the sound of his radio, he wondered aloud why state lawmakers are out to get him. “I have nothing to hide,” he said. “Just come up here and talk to me.”

Grismore was charged with simple assault after repeatedly kicking a handcuffed and shackled man in custody at the sheriff’s office last August (he has pleaded not guilty, and the case is ongoing). He’s also being investigated by Vermont State Police over alleged financial wrongdoing uncovered during an audit of the office in January.

A law firm hired by the House impeachment committee is looking into these and other allegations against him, and is due to report on its findings by mid-October.

But driving along Route 105, the sheriff said he’s more certain today than he has ever been that, in kicking Jeremy Burrows last year, he did nothing wrong. He asserts that he has only ever kept financial records by the books. He will, he is certain, “be vindicated.”

In the meantime, Grismore, who took office in February, has been making Franklin County’s largest law enforcement agency his own.

Grismore noted that he has been negotiating new policing contracts with at least three towns, in part to make up for the impending loss of a lucrative patrol agreement with St. Albans Town. He said he is stationing officers across more parts of the county to better serve some smaller communities, and said he’s raised pay for part-time employees.

Bryan DesLauriers, chair of the St. Albans Town Selectboard, called the allegations and criminal charge against Grismore “very concerning,” though said he had seen no issues with the sheriff’s office meeting its contractual obligations there this year. Town officials have been adamant that the decision they announced in January not to renew their contract with the sheriff’s office had nothing to do with Grismore’s conduct.

‘It definitely takes a toll’

Almost every day, Grismore said, he dons his tactical vest and hits the roads to back up deputies at calls all over Franklin County. The investigations into his actions, he said, haven’t dampened his desire to do the job; he said he feels support countywide.

But Grismore acknowledged that the criminal charge and investigations have impacted his ability to do his job. “It definitely takes a toll,” he said. “My credibility, my reputation, my mental health, my effectiveness as a leader — it’s always compromised by negative things, right?”

After more than an hour on the road, neither Grismore nor his deputies had been able to track down the girl with the knife, and the sheriff began the drive back to his office in St. Albans Town.

Since Grismore has been charged with a crime, he has lost access to some of the key tools of his trade: Valcour, a computer system used by police throughout Vermont, and the National Crime Information Center, a national criminal records database.

Valcour helps public safety agencies dispatch services, gather data, exchange information, and manage records — such as reported crimes, stolen property, and people who are arrested. The national database, meanwhile, holds information about wanted and missing persons, stolen property and domestic violence protection orders. Police can also use it to run criminal history checks and access the national sex offender registry.

Under the state’s rules, other authorized users at the Franklin County Sheriff’s Office can continue to use both databases, but are barred from sharing the information with Grismore. When asked, the sheriff said he’s abided by these rules.

Grismore said lack of access to the police databases has made his job more difficult. There are times, for instance, when he is out on the road and it would be easiest to look up a suspect’s name on his computer. Instead he has to rely on information that is transmitted over the agency’s police scanner, which is accessible to the public.

But the sheriff pushed back on the suggestion that this has made him a less effective police officer, saying it would be a larger issue if he were regularly making arrests, but he’s primarily focused on administrative and business tasks at the office.

Administrative work is what got Grismore in the door at the sheriff’s office in the first place. After years working in corporate security, and a part-time stint at the St. Albans Police Department, Grismore joined the county sheriff’s office in 2018 to help then-sheriff Roger Langevin keep the books.

At the sheriff’s office, he started taking on more police work, and eventually worked his way up to become the department’s No. 2. Grismore held the title of captain when Langevin fired him, in late August of last year, for kicking Burrows.

Grismore said he only started to consider running for sheriff after Langevin asked him to be his successor — and even then he had to be persuaded. He described feeling pressure to run for the top office, saying Langevin “was almost bullying me into doing it.” (Langevin could not be reached for comment for this story.)

A Republican, Grismore was the only candidate on the ballot for Franklin County sheriff last November. After news broke that he’d kicked a shackled suspect, both the local Republican and Democratic committees urged him to drop out, and threw their support behind Mark Lauer, one of two men mounting last-minute write-in bids for the office.

Despite those efforts, Grismore won by nearly 3,000 votes.

‘Let’s talk about it’

But while a majority of Franklin County voters wasn’t put off by Grismore’s behavior, the state organization that oversees police certification has proven less willing to move on.

The Vermont Criminal Justice Council is set to hold a hearing on Oct. 17 to decide whether to revoke Grismore’s police certification. The hearing was originally scheduled for August, but was postponed at the request of Grismore’s attorney, in part because the sheriff had not found anyone to testify on his behalf.

Grismore received his initial Vermont law enforcement certification in 1997, and his Level II certification in 2014, according to recent council filings.

A charging document prepared by the council outlines the potential case for revoking Grismore’s Level II certification. It states that he may have violated the state’s use-of-force policy when he kicked Burrows because his actions were “disproportionate to the conceived concerns and an unreasonable use of force given the totality of the circumstances,” including the fact that two other deputies were present in the room.

Both deputies later told a state police investigator that they thought Grismore’s use of force was excessive, and one said she intentionally moved her body to block Grismore from kicking the shackled man more, according to court records.

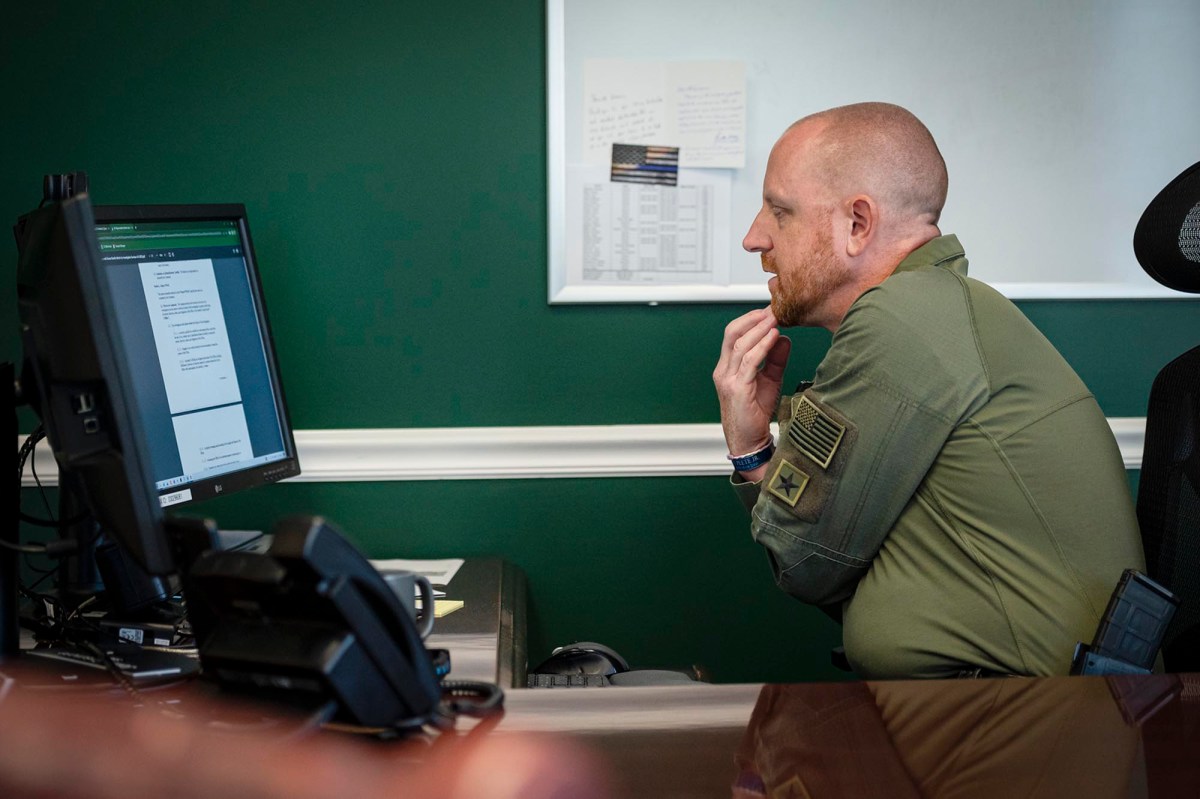

Sitting behind his large, wooden desk back at the sheriff’s office, Grismore seemed unconcerned by the prospect of losing his certification. He pointed out that Vermont law does not require sheriffs to be certified law enforcement officers.

Grismore’s certification status is just one of several lines of inquiry that the House impeachment committee has tasked a law firm with investigating. It’s also exploring whether he committed financial misconduct, and violated the public’s trust.

Last month, the committee accused him of dragging his feet in response to a subpoena. Grismore pushed back against that characterization in an interview, saying the request was simply too large for him to respond to in the time frame the lawyers gave him.

The subpoena has been a tax on his department’s resources, said Grismore, who expressed frustration that he and his staff have had to search for documents when they could be doing police work.

Franklin County’s sheriff said he has been too busy running his roughly 30-person department to pay much attention to the impeachment committee’s work this summer. He hadn’t seen the list of topics for which the House’s lawyers are investigating him, as laid out in a contract with the state, until a reporter showed him.

“That’s pretty fucking broad,” he said after taking a first look at the document. He appeared eager to talk through each topic, urging a reporter to continue lobbing questions at him.

He questioned why lawmakers chose to pursue impeachment, rather than come to him directly with their concerns about his actions. “They could say well, John, you signed a check for this and we don’t think that it’s appropriate. So let’s talk about it,” Grismore said, though didn’t appear to have a specific check in mind. “But they’d rather fan flames in the media, and make it look like I’m not doing what I’m supposed to be doing.”

Grismore also suggested if there had been any financial misconduct, it would not be his fault — or at least not solely his fault. Langevin, the former sheriff, “signed off on everything,” Grismore said. “There wasn’t a penny that came in or left that office that he didn’t approve in writing.” And he said the committee should take up its concerns about financial mismanagement under his administration with his business manager.

Rep. Martin LaLonde, a South Burlington Democrat who chairs the impeachment panel, said last week that the committee is investigating Grismore’s conduct both before and after he was elected sheriff. LaLonde said the committee would be open to having a direct conversation with Grismore, but it likely wouldn’t happen until October, at least.

The committee’s work — much of which has been shielded from the public in executive sessions — is happening as fast as it can, while still “being thorough,” LaLonde said. “But I absolutely appreciate the pressure that we have in needing to come to a resolution for the people involved.”

‘All this garbage’

Grismore said the scrutiny applied to his use of force against Burrows last fall has had repercussions for other law enforcement officers in the state.

“I won’t tell you who, but I’ve talked to another member of law enforcement leadership in Franklin County who said that there are people who don’t want to use force anymore. They’re afraid to,” he said, gesturing and leaning forward in his desk chair as he spoke. He suggested that was problematic, if not dangerous, because there are certain situations in which police officers have to use force.

Langevin has called Grismore’s use of force an “egregious incident,” and other law enforcement officials have condemned it as well.

The incident also prompted Grismore to rethink some of the agency’s operations, he said. The sheriff’s office no longer publishes mugshots and press releases on its Facebook page, he said — a policy Grismore said he implemented because he saw misinformation and undue judgment on social media about himself last year.

Grismore said he feels badly for the deputies in the sheriff’s office, who have seen their workplace “get dragged” online and who, he noted, may well have to testify in court as part of the criminal case against him. Many of the deputies have “stood by me through all this garbage,” he said. “And I need to try to repay their debt of loyalty.”

Asked if he feels responsible for that — because he was the one on video kicking a detained man — Grismore was quick to answer “no.” He has no regrets about his own conduct, he said, but does regret how others, including the media, portrayed it.

“I’m not the one who put it all out there,” he said, adding that it was Langevin’s decision to release video footage of the incident and then send out press releases about it.

More than anything, though, Grismore said he feels an obligation to voters to continue serving as sheriff. He said he is regularly thanked for doing his job when driving around Franklin County. In one case, he said, a woman who was being arrested by another deputy turned to Grismore and told him that she thought he was being judged unfairly.

Back at the office, Grismore said he won’t rule out running for reelection in 2026.

“I’m not a very religious person, but some higher being wants me to be in this role,” he said. “Why else would I still be here? Why else would I have gotten elected?”