The Shelburne Museum has cut ties with the acclaimed architect hired to design a new Indigenous art center after he was publicly accused of sexual assault and misconduct.

The allegations leveled against the architect, Sir David Adjaye, led the museum to end the relationship with him and his firm, Adjaye Associates, according to a statement the museum released on July 13, nine days after the Financial Times broke the initial story.

“The recent allegations of sexual misconduct leveled against David Adjaye, and his admission of inappropriate behavior, are incompatible with our mission and values,” said Tom Denenberg, CEO and director of the Shelburne Museum in the statement.

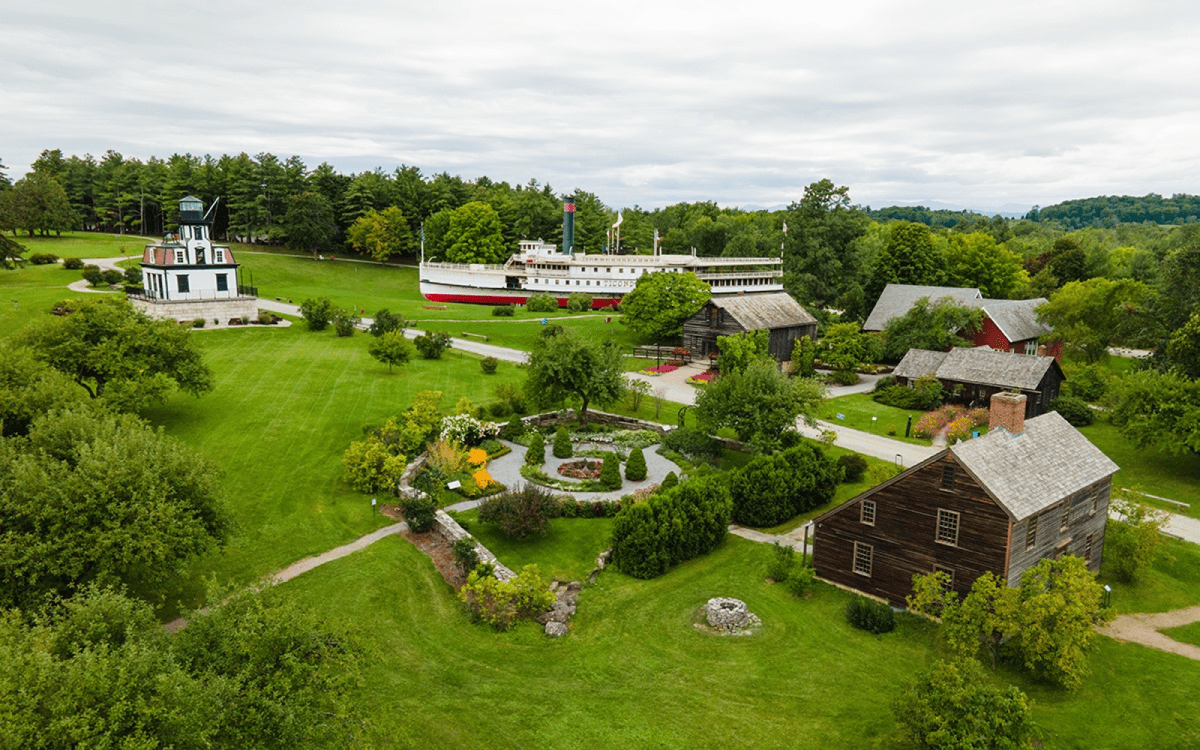

The Shelburne Museum announced in May that Adjaye and his firm had been hired from a pool of 17 architects to design the Perry Center, a new building set to house a collection of Indigenous art.

Adjaye, who was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2017 for his service to architecture, is a Ghanaian-British architect whose work includes iconic buildings such as Ghana’s national cathedral, an African art museum in Nigeria, a multifaith center in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates and National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Clients around the globe quickly cut ties with Adjaye within days of the Financial Times’ report about him. Published on July 4, the article detailed a series of accusations from three of the architect’s former employees of sexual violence and other forms of exploitation.

Denenberg said in an interview that on July 5, he initiated internal communication with collaborators and museum board members about how to respond.

Shelburne Museum officials reached a unanimous agreement also to sever ties with Adjaye by July 11, Denenberg said, but waited to announce the decision until July 13 due to the flooding that occurred in Vermont last week.

“We’re not going to put a press release out when someone’s getting washed away,” Denenberg said.

In the public statement, Denenberg said that the Perry Center project will continue more or less on schedule, with plans to hire a new design architect by the fall of 2023 and begin construction in the fall of 2024.

The museum remains “committed to moving forward with the project and the many other partners and collaborators who have been involved since its conceptualization,” he said.

With less time to find a new design architect, Denenberg said the museum is hiring from a smaller pool this time — five invited architects or firms rather than 17.

Museum officials are seeking someone who can nimbly step into the evolving vision for the project, Denenberg said.

Denenberg said that the museum has already been engaged in a partnership with Two Row Architect, a “100% native-owned business operated from the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation and Tkaronto.”

Two Row Architects was hired to “organize listening circles with Indigenous tribes and to advise or … translate what we were hearing from multiple indigenous voices or groups,” Denenberg said.

Denenberg did not confirm whether the museum is considering Two Row or any other Indigenous architects or firms to replace Adjaye’s role in designing the structure. He said he feels that hiring an Indigenous architect to design the project is not particularly easy, nor necessary.

“One of the challenges is the way the architecture field has grown — it’s no different from any other — (is that) a lot of people were left out over the years so you don’t have a huge pool of Indigenous architects,” Denenberg said, “which is the same thing with Indigenous curators.”

The Shelburne Museum’s current Indigenous art curator, Victoria Sunnergren, who is not Indigenous, is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Delaware studying Indigenous art.

When plans to create the Perry Center were first announced, Beverly Little Thunder — a Lakota elder, women’s activist, member of the Standing Rock Lakota Band from North Dakota and long-time Vermont resident — expressed concern about the lack of Indigenous representation in the museum’s curatorial role and name of the center itself.

“I do feel that one can have empathy for another culture and a professional can understand and take care of somebody else’s material according to the best practices of that culture,” Denenberg said. “I don’t think it has to be an Indigenous architect from the outset, although we have from the beginning said this is all about listening to Indigenous voices.”