Editor’s Note: Student journalists from more than a dozen schools across Vermont contributed to the Climate Report Card series, reporting on their schools’ systems for heat, electricity, transportation, food, and climate education. Each article in the series collects a handful of accounts from participating schools; together these stories show that our school communities are working hard to be more energy efficient, and that we face complex trade-offs in seeking to reduce our carbon footprint. The project does not claim to be a complete or authoritative evaluation: its core purpose is the students’ civic engagement. Special thanks to Mariah Keagy her colleagues at VEEP for their generous collaboration.

The Underground Workshop’s Climate Report Card series was compiled, organized and edited by a team of student editors: Anika Turcotte, Montpelier High School; Adelle Macdowell, Lamoille High School; Anna Hoppe, Essex High School; Mei Elander, Enosburg Falls High School; and Cecilia Luce, Thetford Academy

Contents

One System in Focus: Wood Chip Heating At U-32

Snapshots:

Champlain Valley Union High School, Hinesburg

Lake Region High School, Barton

Twinfield Union School, Marshfield

Bellow Free Academy, St. Albans

Other Findings: St. Johnsbury Academy, Essex, Montpelier

Introduction

by Anna Hoppe, Essex High School

By one vote, the Vermont legislature failed on May 10 to pass one of the biggest climate related bills of the session: the Clean Heat Standard. The vote on the 10th was an attempt to override Governor Scott’s veto on May 6th.

Another bill, H.518, would give grants to municipalities to switch to clean energy, and while it originally included public schools, the final version excluded them.

Without a broad standard in line with the goals set out in the state’s Climate Action Plan, schools’ responses to the climate crisis are not always consistent, and some of the heat sources used, mainly wood chips, are part of the reason that the Clean Heat Standard did not pass.

Some climate justice advocate groups like Biofuel Watch and 350 Vermont had criticized the inclusion of biofuels like wood because of their potential impact on the climate and land use, while other environmental groups like the Vermont Natural Resources Council supported the bill.

Despite the lack of strong statewide incentives and guidance, schools across Vermont are working to reduce the impact of heating, which currently accounts for about 34% of the state’s emissions.

One System In Focus: Wood Chip Heating at U-32

by Charlie Haynes, U-32 High School

Each week in the winter tractor trailer trucks arrive at U-32 High School in Montpelier, Vermont. The doors of the trailer swing open, revealing 30 tons of wood chips. The trailer floor is broken into 3 sections that work together, sliding back and forth to “walk” the chips out of the trailer and into a concrete and steel pit. The pit holds 70 tons of wood chips, and feeds the heating system. In the last three years, U-32 has burned on average 960.58 tons of wood chips each winter.

A question arises with this system: How sustainable is wood chip heating for Vermont’s schools?

Not everyone is convinced wood chips are the way to go. William Schlesinger is a biochemist, and member of the US Environmental Protection Agency Advisory Board. “When you cut down existing trees and burn them, you immediately put carbon dioxide in the air,” he said, in an article in the Guardian. “None of the companies can guarantee they can regrow untouched forest to capture the same amount of carbon released.”

Despite this, biomass heating still does work for climate change, says Andrea Colnes from the New England Forestry Foundation. “There is a strong alignment between doing really good forestry, and the need for markets for that low-quality wood, that can help pay for that forest management over time,” Colnes said in a Maine Public Radio article. “So they really do fit together.”

The sustainability depends on how easily the wood chips can be supplied, and the process for sourcing them.

This past winter the school only burned 820 tons of wood chips, because there was a period of time when their usual supplier was unable to consistently supply wood chips, according to Chris O’Brien, Director of Facilities for the district.

The school’s usual supplier is Limlaw Chipping & Land Clearing, Inc. The owner, Bruce Limlaw, said that he had not had significant issues with supplying wood chips this winter, and that U-32 school had switched to getting their wood chips from Cousineau Forest Products. In the interview, Limlaw did say that there had been troubles with “the green people, such as people who don’t want the trees cut.”

According to Jim Donelly of Cousineau Forest Products, the school’s current supplier,, the wood chips burned at U-32 are all sustainably harvested, as a byproduct from logging operations. He said once trees are harvested, they are sectioned into thirds. The bottom section is the saw log, long and straight enough to be used for lumber. The middle part is pulp wood, used for firewood, or making wood pallets. Lastly, the top third, which is considered biomass, is either turned into wood chips, or left to decay and return to the earth.

Wood chip heating is still tied to oil in a couple ways.

Despite the wood chip boiler, U32 still burns approximately 15,000 gallons of heating oil yearly as well. This is backup heat, but also responsible for hot water production. Oil is also used to produce the wood chips, as all the logging equipment is petroleum powered.

#2 Fuel Oil (typical heating oil) is currently $5.97 a gallon as of May 2022, compared to $2.64 in May 2021, according to the State of Vermont Public Service. According to Jim Donelly of Cousineau Forest Products, there has been little change in the price of lower grade wood chips so far. The high oil prices will raise wood chip prices, he said, but “luckily the price of chips will stay well below the cost of other fuels for heating by comparison.”

The future of heating at U-32 is pretty certain for now. The wood chip boiler at U-32 is just over 20 years old, but according to Matt Colburn of Messersmith (the company who made the system), it isn’t even half way through its life. The boilers they make are highly serviceable, and “as long as the systems are cared for and maintained they will last over 50 years.”

Each winter day inside the pit, a small auger slides from the front to the back wall, and pulls the wood chips onto a small conveyor belt to the hopper, a box roughly 2’ by 2’ by 3’ with two sensors on opposite sides. Once the chips pile up and block the sensor’s line of view, it stops calling for chips. At full operating speed, this occurs every few minutes.

From this hopper, two very small augurs pull the wood chips into the firebox, where they are burned and turned into heat to keep the school’s 200,000 square feet warm, all winter long.

Once all those wood chips are burned, Bob Weinstein, a member of the maintenance staff, puts on a full fire retardant suit daily to clean out the ashes. He shovels the ash into metal trash cans. A few times a winter the system is completely shut down for cleaning. After these complete shut downs Weinstein shovels wood chips into the boiler, and lights them by hand to start the boiler once again.

Snapshot: Champlain Valley Union High School, Hinesburg

Reporting by Emma Crum, Alyssa Hill, and Anna Van Buren

CVU is heated by a wood-chip boiler system, which members of the CVU Environmental Action Club toured on March 15th. Tom Mongeon, the Director of Maintenance at CVU, led the tour. CVU’s wood-chip boiler system was installed in the fall of 2005, and the school sources wood chips from a Bristol company called A. Johnson.

CVU used to consume around 30,000 gallons of #2 fuel heating the school per season. They installed the wood chip system in 2005. Katie Antos-Ketcham is the advisor for CVU’s Environmental Action Club. “We were really excited about not burning #2 fuel oil to heat CVU, and turning to locally sourced wood chips as our heating fuel source instead,” she said.

CVU continues to look for ways to conserve. The school uses natural gas to heat water in the summer, so as not to have to run the wood chip boiler. But the system depends for its sustainability on the supply. Alyssa Hill, a ninth grader and member of CVU’s Environmental Action Club, researched wood chip heating and has concerns. “If trees are being cut down and burned without replacement, their carbon footprint will well surpass that of coal,” she said.

Snapshot: Enosburg Falls High School, Enosburg

Reporting by Mei Elander

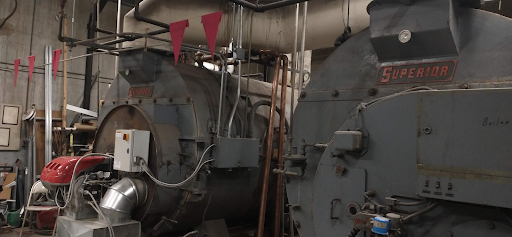

Photo by Mei Elander.

COVID-19 impacted heating efficiency at Enosburg High School. Even after the mask mandate was lifted, the school’s ventilation remains open to allow for more airflow. With vents open, the cost of heating the 121,000 sq foot building has increased significantly.

Enosburg converted to natural gas when it became available, six years ago. The estimated cost was $150,000 to convert to natural gas because they had to convert burners to dual fuel burners. However, the payback was under five years and it both burns cleaner and saves taxpayers money.

“The thing about burning natural gas is once it’s piped underground into your school you don’t have to worry about deliveries,” said Doug LaCross, Director of Building and Grounds. This means that there would be less energy required to transport fuel to the school.

Snapshot: Lake Region High School, Barton

Reporting by Tressa Urie

Snapshot: Twinfield Union School, Marshfield

Reporting by Hunter Wheeler and Hazel O’Brien

Twinfield Union School in Marshfield upgraded to new boilers in 2017, and installed new thermostats in every room in 2020-2021, to better control air quality and desired heat. Twinfield uses wood pellets for primary heat, with propane as a backup, burning roughly 200 tons of pellets each year, along with 1-2,000 gallons of propane. The school purchases pellets from Morrison’s Feed Bag, and the pellets are made in Maine.

Brandon Lawrence is head of maintenance at Twinfield and operates the pellet boiler. He said the system has been reliable and that it helps to be able to control it remotely. “I can’t really say anything negative about burning pellets,” he said. “One positive is that from year to year the costs of pellet fuel seems to stay very steadily priced unlike oil and propane.”

Snapshot: Bellows Free Academy, St. Albans

Reporting by Emily Hayward

Bellows Free Academy St. Albans (BFA) has two main school buildings, which are known as the North and South buildings. The school was originally built in 1883 by Chauncey Warner. Before the district purchased the North building in 1996, it was a hospital.

A fire burned down the hospital only five years later, and it was destroyed. The owners used the opportunity to improve the building completely. Another hospital in Saint Albans opened up in 1950, called Kerbs Memorial Hospital, which led Bellows Free Academy to buy the original hospital building to add to its private school for boys.

Currently, BFA uses gas and oil steam boilers in both its North and South buildings. Frequent complaints about the school’s heating regard the inconsistent temperatures.

“In the North building, whenever I go to AP Bio it is always so cold,” said senior Erika Hart.

“The heating for me at least depends on who’s room you’re in,” senior Grace Peyrat said, “but generally BFA North seems to have colder rooms.”

Over the next twenty years, the school has plans to improve the heating systems. In particular, the hope is to install more air conditioning during the summer. There are also plans to fix the heating at the Maple Run district office, replacing old heating equipment, and improving natural light to reduce the need for electricity.

The plan to improve the efficiency at BFA intends to improve HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) equipment by updating to newer models and improving insulation. The total cost of all the updates to the school is $10,536,957 with a yearly escalation cost of 3%. In the next 20 years, it is planned that 25 million dollars will be spent on renovations. Concerns about the heat and electricity renovations include costs, as well as the reliability of new equipment. The equipment has never been used before, and the maintenance staff does not have experience working with similar technology.

These are complex questions with no easy answer. The heat coming from the furnaces in our schools is only the tip of a very complex and intricate iceberg. Despite these lingering questions there is a positive trend: greener heating options are getting cheaper, and many schools seem to be on a path towards making their heating systems more environmentally friendly.

Other Findings: St. Johnsbury Academy, Essex, Montpelier

by Anika Turcotte, Montpelier High School

St Johnsbury Academy (435,660 ft) plans to install cold climate heat pumps. These upgrades are limited by the lack of space for a central plant and the cost of electricity.

At Essex High School, Chief Operating Officer Brian Donahue said that the plan is to “regularly maintain the systems and try to optimize them.” But there hasn’t been any major replacement of the systems overall. The school is currently heated with natural gas and a transition to alternative heat sources is limited by the school’s size (300,000 sq ft) and the building’s age. There are no immediate plans for system improvements.

At Montpelier High School, Andrew LaRosa, Director of Facilities, explained there have been proposals to switch away from an oil heating system and to integrate vegetable based bio heating oils. The issue is finding a reliable source. Small scale producers make the fuel but none that the school district deems a steady, long-term supplier.

Additionally, there is very little precedent. No nearby schools have tried the alternative heat source and LaRosa just hasn’t seen a full switch as worth the risk. “My number one job is that Monday morning, you guys come to school, and it’s warm, and it’s safe, and it’s clean,” he said. The school also hopes to install new circulator pumps and incorporate recycled air.

Lingering Questions

by Mei Elander, Enosburg Falls High School

As we zoom in on the heating systems of particular schools, questions emerge:

- Where is the fuel coming from? When wood chips or wood pellets are no longer byproducts, but are the reason for cutting trees how does that affect the “greenness”?

- How do we determine the sustainability of our fuel supply? One must track the transportation, the factory, the drilling, and the byproduct.

- Would it save more energy to make buildings more efficient by upgrading older parts or adding insulation, rather than shifting to a different heating system?

- What is the best way to spend money to make a school’s heating system more efficient?