BRIDPORT — On the hunt for a set of GPS coordinates, biologists from the Vermont Center for Ecostudies ambled up an untrailed slope of Addison County’s Snake Mountain in late April.

After climbing upward a few hundred feet through the forest, they began to hear the chirp of peepers — a signal they’d nearly reached their target location.

Soon, the group came to a clearing in the trees, cradled between ledges of rock. It held an ephemeral body of water, swollen with snowmelt and April rain, a little longer than a tennis court. Beyond it, a series of other vernal pools sat between the ledges, oases for forest creatures that need water to breed and develop.

In vernal pools, egg sacks and young amphibians are safe from some of the usual water predators, such as fish and green frogs, which need year-round water bodies to survive.

Upon arriving, staff members with the Vermont Center for Ecostudies — Kevin Tolan, Nathaniel Sharp and Emily Anderson — got to work. Wading into the water, they took note of the various species that call the pool home each spring before it shrinks to a puddle.

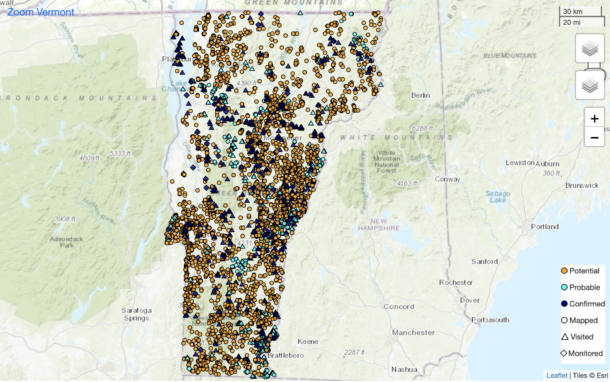

The organization, which collects data about ecology in Vermont — often with the help of citizen scientists — has been working for years to assemble an atlas of vernal pools in the state. Using remote imaging, staff at the center have pinpointed thousands of potential pools, but until they’re confirmed, the pools aren’t protected.

To that end, the organization is looking for help from Vermonters.

Pools are only visible in the spring, making them easy to miss — and susceptible to development.

“Even though vernal pools technically have legal protections, if you go there and it’s not mapped and there’s no pool there because you went in mid-August, you might still develop over it,” Tolan said.

If a pool is destroyed before being mapped, it’s hard to prove it ever existed.

Vernal pools are seasonal wetlands that fill with water in the spring and usually dry out in the summer. They have no inlet or outlet for the water to continue its flow. Their drying is important, Tolan said, because it prevents fish and other predators from getting established, giving other species — spotted salamanders, fingernail clams, fairy shrimp and wood frogs — a safe nursery.

All of the state’s frogs and toads and most of the state’s salamanders require some kind of wetland for parts of their lives, said Zapata Courage, a district wetlands ecologist based in Addison County with the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation.

“For some of those species, such as the wood frog and the spotted salamander, that becomes even more narrow in that vernal pools become those priority wetlands for breeding,” she said. “Their options on the landscape become much more limited, and therefore the destruction of one wetland or one vernal pool may mean that they have to travel a lot further to get to the next one.”

Vernal pools are considered significant Class II wetlands whether or not they’re mapped, Courage said. The state designates three categories of wetlands, with Class I being considered “exceptional or irreplaceable in their contribution to Vermont’s natural heritage.”

Landowners are required to maintain a 50-foot buffer, where development is prohibited, around Class II wetlands. Class I wetlands require a 100-foot buffer, and Class III wetlands don’t require a buffer.

“That’s important for landowners to know, only because a lot of those vernal pools are small, they are seasonal most often, they may not always be readily identifiable as wetlands, and consequently, they’re also underrepresented and under-mapped because you can’t see them through the canopy of the trees,” Courage said.

Any activity that changes the landscape within a Class II or III wetland likely requires a permit from the state, Courage said. Landowners can check to see whether they might have wetlands on their properties through the state’s wetland screening tool.

A lot of the state’s original mapping, completed in the 1970s and ’80s, didn’t pick up vernal pools, she said, though the state is currently trying to improve its maps. Courage said she recommends reporting vernal pools to the Vermont Center for Ecostudies.

She said the Department of Environmental Conservation and the Vermont Center for Ecostudies are working to share the information, though that exchange hasn’t yet been perfected.

Tracking the pools could become even more important as climate change alters Vermont’s weather patterns, she said.

“Looking at the dispersion of where these vernal pools are can be really important, as things might begin to shift higher in elevation or we’re further northward according to climate change pressures,” she said. “For long-term monitoring, it would be nice to know where these vernal pools are.”

Participants in the organization’s Vernal Pool Atlas program fill out data sheets to identify pools and the critters that reside within them. Pools on private property require landowner approval before they’re confirmed.

Those interested in identifying vernal pools can sign up at VPAtlas.org.