In April 1987, seventh grader Kristine McGuire told two New York detectives something she had never before told an adult: A year earlier, the father of a classmate had fondled her while she was on vacation with his family in Florida.

She had stayed with the family for about a week on their yacht. She said the father, Leonard Forte, who was in his mid-40s, had touched her inappropriately when his wife had been away.

Back home, the 12-year-old told authorities she knew the touching was not accidental.

“I was embarrassed and uncomfortable,” she said in a sworn statement to New York police on April 20, 1987, “but I didn’t know what to do.”

Yet, she never heard back from anyone about her complaint against Forte.

“It was confusing for me because I thought that what happened to me was wrong,” said McGuire, who is now 47. “It affected how I viewed men and relationships and right from wrong. It did a number on my psyche.”

What left the biggest impact on her younger self, McGuire said, was that lack of response from authority figures. They appeared uninterested in learning more about the incident, which, as an adult, she understands was molestation.

She did not know until a few years ago that Forte — a retired investigator with New York’s Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office — had been convicted in 1988 on three charges of child sexual assault in Vermont.

A classmate named Michele Dinko, accompanied by McGuire in April 1987, described to their assistant principal being raped by Forte while she was vacationing with his family in Landgrove that February. Forte faced a sentence of up to 60 years in prison for three counts of sexual assault against the 12-year-old.

But what unfolded in the next three-and-a-half decades landed the case in Vermont’s record books: State v. Leonard Forte, case No. 1031-7-87 BNCR, became the longest-running criminal case in state history.

It has cast a shadow over Vermont’s criminal justice system, raising questions about how just the system is, what loopholes a defendant can take advantage of and how crime victims can find closure when it eludes them in the courtroom.

How could this happen?

“Leonard Forte was an extraordinarily clever liar,” said former Vermont Attorney General Jeff Amestoy, offering his view on why the case stalled for decades. “He was able to fool not only the judicial system, but significantly, the health care system.”

Dinko, in order to move forward with her life, said she tried to forget the incidents with Forte.

“Justice has not served me,” she told the court in March. “I am not that important? It’s OK for you to be raped, and Mr. Forte not be held accountable for another trial. I can never wrap my head around why this happened.”

From state prosecutors’ accounts, the trouble started in 1989. Before Forte could be sentenced on his three sexual assault convictions, Judge Theodore Mandeville Jr. decided to throw out the guilty verdicts. The judge granted Forte’s request for a new trial, based on an argument that the prosecutor, Deputy State’s Attorney Theresa St. Helaire, had prejudiced the Bennington County jury by being too emotionally involved in securing a conviction.

From St. Helaire’s opening statements onward, Mandeville said in his written ruling, the prosecutor’s demeanor “can only be described as a fury seldom seen this side of hell.”

The Vermont Attorney General’s Office appealed Mandeville’s decision with the state Supreme Court, decrying it as “grounded in gender bias.” The Supreme Court, however, upheld the judge’s ruling.

After nearly a decade of failed attempts to reimpose Forte’s convictions, the attorney general’s office decided to charge him again in 1997. Forte, who was by then living in Florida, asked for the charges to be dismissed because he had a terminal heart illness that made him unable to withstand another trial — assertions he maintained until 2021.

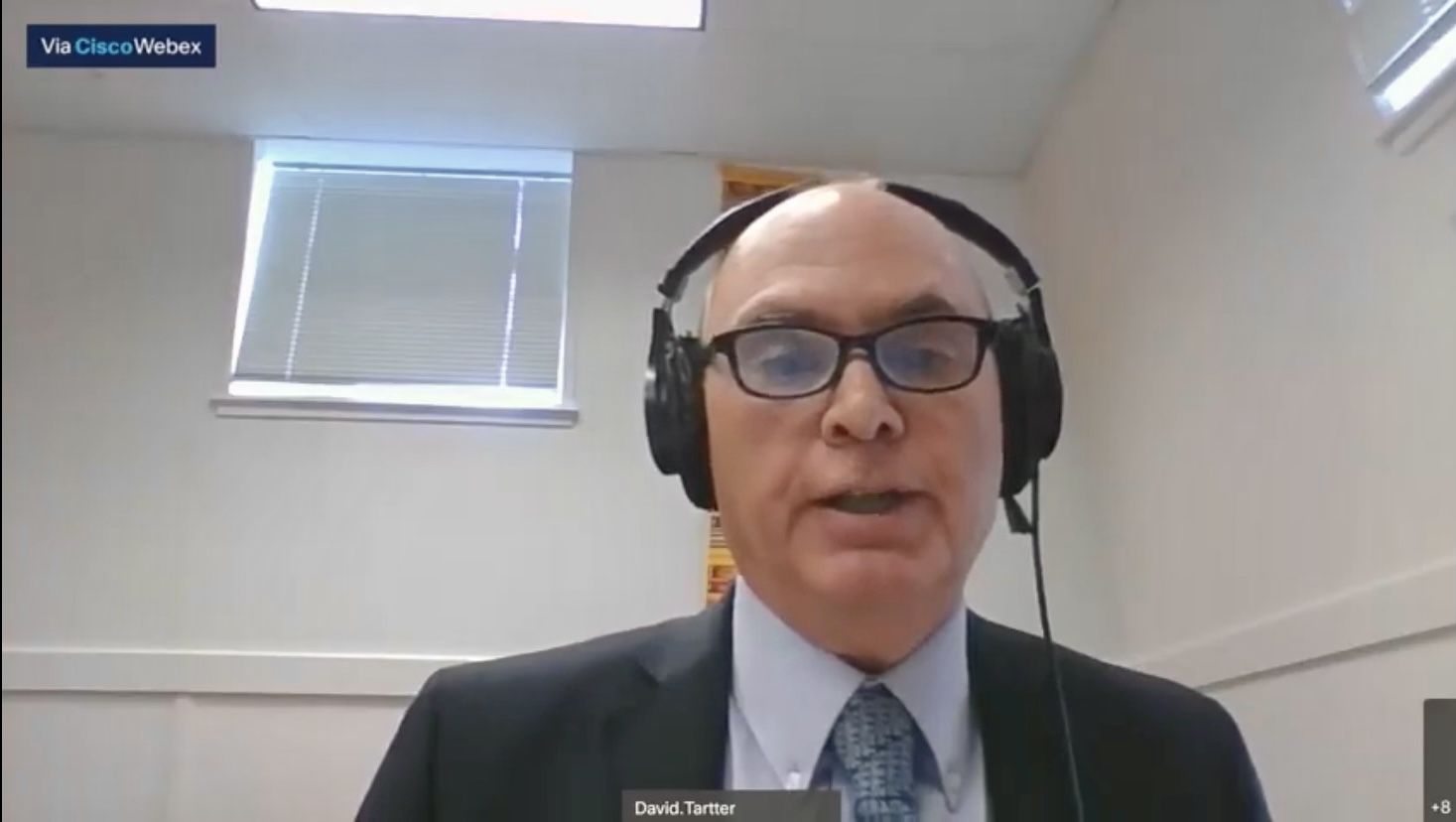

Assistant Vermont Attorney General David Tartter, the new prosecutor who oversaw the case until 2019, agreed to put a retrial on hold until Forte’s health improved. Forte was required to provide the court with updates on his health every six months.

And so, Forte’s prosecution remained in limbo for the next 22 years even while Dinko maintained her willingness to testify at his new trial.

Forte phoned in to the Bennington court to discuss his health status once or twice a year — until late 2019, when USA Today published an investigative piece that called into question Forte’s claims of a grave illness.

Among the people who read the story was Amestoy, who, as Vermont attorney general in the 1990s, had twice argued before the Vermont Supreme Court for the reinstatement of Forte’s convictions. Until he read the news article, Amestoy said he did not realize deceit could have been involved in Forte’s claims of ill health.

Amestoy approached Brian Burgess, a former assistant attorney general who had also worked on the Forte appeals, about coming out of retirement so the two men could act as special prosecutors in the case. They would be working for free.

Amestoy and Burgess then went to the current attorney general, TJ Donovan, with their suggestion: assemble a prosecution team dedicated to taking Forte to trial. They requested that the team be led by Linda Purdy, an assistant attorney general in the criminal division who once led the office’s child abuse unit.

Amestoy and Burgess brought a lot of experience to the team: Amestoy had been chief justice of the Vermont Supreme Court, and Burgess had been an associate justice, after both served in the attorney general’s office. Even so, each had to reapply for a law license to join the Forte prosecution.

Amestoy said he felt very strongly about the case because it represented to him the “worst of the worst” criminal offense: the sexual assault of a child by a law enforcement officer who took advantage of a family relationship.

In June 2021, following a series of hearings, the team scored a major victory. The new presiding judge, Cortland Corsones, ruled that Forte, 79, was physically capable of undergoing another trial.

“The evidence demonstrates that the defendant exaggerates the limitations on his activities,” Corsones said in his written decision. “The defendant is able to safely travel, when it is something he wants to do.”

A jury trial was scheduled for spring 2022, though no exact date was given.

Purdy, who was named a deputy state’s attorney so she could continue prosecuting the case after retiring from the attorney general’s office, began planning for the trial as 2021 came to a close. She was confident Forte’s retrial would take place the following year despite defense attorneys’ request for an evaluation of his mental competency to undergo a trial.

“I was telling our prosecution team, ‘Everybody have a nice holiday and take some time off because when we come back, it’s going to be all hands on deck,’” she said. “This is gonna be a tough case to prove because it happened 35 years ago, but we have the evidence, and we’re gonna work hard.”

But on Dec. 22, the prospect of a retrial evaporated. Forte, 80, died of sudden cardiac arrest at his house in LaBelle, Florida, a city just east of Fort Myers.

Dinko, now 47, said she felt a mixture of disbelief, anger and sadness at the news.

“I didn’t get my trial. He dodged the system yet again,” she said in court in March.

Gender bias

Prosecutors say the criminal justice system failed to hold Forte accountable on the allegations he repeatedly raped a child in Vermont. They say Judge Mandeville, now deceased, derailed the quest for justice when he reversed the jury’s three guilty verdicts, a decision they maintain was rooted in gender bias. And it stayed off track because of what they describe as systemic loopholes and Forte’s manipulation of the system.

On the gender bias argument, Purdy points out that Forte’s trial jurors, called to testify in 1990, said they did not find the female prosecutor overly emotional — the key issue Mandeville cited in his ruling. They said her demeanor had not affected their findings, and they were surprised to learn that the judge had thrown out their verdicts.

“What happened was a gender-biased male judge overturned the verdict, not based on the evidence,” Purdy said. “None of his decisions were based on the evidence.”

Amestoy calls Mandeville “extraordinarily sympathetic” toward Forte, since he was a former law enforcement officer. Society in the 1980s, Amestoy said, also was not as aware of child sexual abuse as it is now.

“At that point in time, there was just a disbelief that children were being abused sexually,” he said. “And of course, it would be even less likely for most jurors to think that a law enforcement officer could possibly have done it.”

Mandeville died in July 2020. His son and namesake, Ted Mandeville, declined to comment for this story, saying he had no knowledge about the Forte case.

“I don’t remember anything about that case, and my father never told me anything about that case,” he said in a phone conversation.

Decades on the docket

Amestoy said his office tried for eight years to reverse Mandeville’s order for a new trial, not wanting Dinko to go through the ordeal of testifying again — an experience she now describes as the scariest of her life. She was 14 then and recalls being embarrassed and ashamed to explain her sexual assault allegations to a roomful of strangers.

Purdy believes there was a lack of accountability among officials who handled the case, such as judges, prosecutors and their supervisors.

“I think there’s plenty of blame to go around in terms of why did it get delayed for so long,” she said. “Why wasn’t somebody saying, ‘This case has been on the books now for 20 years’?”

Vermont judges, for instance, get rotated from court to court once a year or every two years. Under this arrangement, Purdy said, the current presiding judge may not fully understand the history of a case and its ins-and-outs.

“Nobody meant to cause any harm,” she said, “but there was this wholesale lack of awareness of the harm that the delays would cause a child victim of sexual abuse, who had been brave enough to testify in front of 12 jurors and have a conviction on three counts of sexual assault of a former law enforcement officer.”

At the same time, Purdy and Amestoy credited Tartter for keeping the case alive when he could have dismissed Forte’s charges years ago. Tartter brought the case with him when he moved to the Vermont Department of State’s Attorneys and Sheriffs in 2016.

“Some prosecutors would have decided it wasn’t worth the resources or the time,” Purdy said, “and the parties were all out of state.”

Tartter, who became part of Purdy’s prosecution team, declined an interview request.

‘He got better’

Amestoy said the prosecution team wished there had been a more critical assessment of Forte’s yearslong claims of ill health and the documents he presented in court.

State experts determined in 1997 that Forte was too sick to stand trial, but prosecutors now believe he recovered significantly after that and led an active life in retirement.

“There’s no question that he got better,” Amestoy said. “He was certainly well enough to travel, and he did.”

During the pandemic, because of court closures and hearing delays, Amestoy said prosecutors and assisting Florida police had an opportunity to look more closely at Forte’s previous court statements and paperwork.

Their findings resulted in new felony charges against Forte: twin counts of obstruction of justice filed last summer. They accused him of submitting a three-year-old doctor’s note to the Vermont court in 2019 — which stated he was too sick to stand trial — and falsely claiming the note was new.

They also alleged he told a Bennington Superior judge in June 2019 that he was in hospice care, when he had actually been discharged that March and traveled out of state for about three weeks.

But the clock was ticking. Forte was aging, and eventually time ran out.

The miscarriage of justice in the Forte case, Purdy said, has a rippling, damaging effect. She said it devastated Dinko, who never saw Forte retried, and it invalidated the jury’s hard work and trust in the criminal justice system. On top of that, she said, it eroded public confidence that the justice system works.

Purdy said she will never forget Forte’s evasion of justice “through his criminal enterprise of lies and deceit.”

Taking the stand

After Forte’s charges were dismissed in January because he was dead, there was one more thing Dinko had to do. She had to testify when prosecutors asked the court not to wipe Forte’s criminal files, but to keep them accessible as a warning of how the system can be subverted.

Normally, when a defendant dies without being convicted, any pending criminal charges are expunged from the record.

On March 21, three decades after Dinko testified at Forte’s trial, she took the stand again in Bennington’s criminal court.

“Sadly, I stand here in front of you after 36 years has gone by, and justice has still not been served for me,” Dinko said, her voice breaking with emotion. “I was 12 years old, and I was raped by Mr. Forte.”

She said Forte was able to go on with his life after the court threw out his convictions, whereas her life was turned upside-down. Dinko said she carried feelings of shame, grew up thinking she wasn’t good enough, had to undergo therapy and still has a hard time trusting people.

She said her encounter with Forte also affected her parenting. (She rarely allows her daughter and son, now teenagers, to have sleepovers. Most sleepovers are held at her home.)

“I had to find a way to live my life, put this tragedy in a vault,” she said. “Where is there justice?”

Dinko’s own mother, Rosalie Salemme, who died in 2015, wrote to New York officials for years to call attention to Dinko’s stalled criminal case.

Dinko, a trauma nurse, testified that she has persevered in court because it’s what she would want her daughter to do under the circumstances. She called it her “last fight for what is right.”

“This case needs to stay open for all people to see, to learn that this can never happen again to anybody,” she said.

Among the people who showed up in court to support Dinko that afternoon was Theresa DiMauro. A recently retired Vermont Superior Court judge, she was the lead prosecutor against Forte 35 years ago, when her name was Theresa St. Helaire. She last saw Dinko in December 1988, during Forte’s trial.

She and Dinko had an emotional reunion. DiMauro said she repeated the words she told the teenaged Dinko: She was important and she mattered.

Of the multitude of cases DiMauro was involved in as a prosecutor and judge, she said she will never forget the Forte case because of how Mandeville’s ruling affected Dinko.

“The jury believed her 100%,” DiMauro said. “It wasn’t just one count or two counts. It was all three counts, and she was robbed of that.”

She thinks Mandeville was biased against the child complainant and used a female prosecutor as an excuse to throw out the jury’s verdict.

“He chose law enforcement over a female child victim, basically,” she said.

End of an era

Though Vermont never succeeded in retrying Forte, Amestoy finds some solace with the prosecution’s success in helping to rewrite the case’s ending before Forte died.

Last year, the state charged Forte with obstruction of justice, Bennington Superior Judge Cortland Corsones ruled he was physically competent to be retried and Florida charged him with a couple of felonies related to the alleged fake doctor’s letter.

Several weeks ago, the court granted the prosecution’s request to keep Forte’s criminal files open to public inspection. Corsones cited several reasons, including that wiping the files would further traumatize Dinko because there would be no legal record of her long, drawn-out court battles.

“The trial did not go forward in a timely manner, at least in significant part, because the defendant misled the State and the court about the extent of his physical disability,” the judge wrote in his March 23 ruling. “The defendant should not benefit by his actions in delaying the bringing of this case to trial.”

Corsones said expunging or sealing would also deny people access to a unique case in Vermont’s legal history. The case had been pending for 33 years — from 1989, when Mandeville ordered a new trial, until this January.

Amestoy said he and Burgess took on the Forte case because they wanted Dinko to know she had not been forgotten and that the justice system could still advocate for her.

“Michele finally got her day in court, at least in the expungement hearing,” Amestoy said.

Purdy, who plans to retire in June, has been helping index the thousands of pages of documents in the case. This would make it easier for future researchers to understand the twists and turns of this legal saga.

Purdy is also discussing with colleagues how victims’ rights could be strengthened through state legislation — an idea she said was brought up by Dinko’s victim advocate, Amy Farr.

John Campbell, director of the Department of State’s Attorney’s and Sheriffs, said his office will be working with partners such as prosecutors and defense attorneys to come up with recommendations for the Vermont Legislature. The goal, he said, is to improve the criminal justice system, so victims like Dinko get the necessary support and do not fall through the cracks.

The prosecution team also nominated Dinko for the survivor/activist award given by the Vermont Center for Crime Victim Services. On April 29, she received the award, which Purdy said recognizes Dinko’s perseverance and courage in pursuing the charges against Forte despite the “layers” and “decades” of injustice.

“We owe it to Michele and other crime victims to learn from this travesty of justice,” the prosecutor said.

The path forward

Dinko and McGuire, who drifted apart in middle school, have reestablished their friendship. McGuire said that, after the girls’ joint trip to the assistant principal in 1987, they didn’t talk about Forte anymore and eventually went separate ways.

But in 2019, when USA Today began looking into Forte’s pending case, Dinko reached out to McGuire, and they reconnected. McGuire said that speaking to a reporter then about Forte — the first time she did so at length in three decades — helped free her from something that had cast a shadow over her life.

“It healed the inner child,” McGuire said. “Once the light shone on it, it wasn’t as powerful anymore.”

Besides what happened to her, McGuire said she had also been carrying the weight of Dinko’s failed quest for justice as well as their silence with each other about Forte all those years.

Now the women regularly speak by phone, see each other and share life’s milestones. McGuire was present when Dinko married her boyfriend, Craig Whitney, in November.

“I think there’s a bond there that will never go away,” McGuire said of her friendship with Dinko. “I got her. I understand.”

Five months after Forte died, Dinko said she is still grieving at the loss of his retrial, just when it seemed within reach. Some days are better than others, she said, as she cycles through feelings of denial, anger, depression and acceptance.

“I’m trying to just let it go,” she said. “It will get easier. I know it will.”

In a few years, Dinko said, she plans to train as a sexual assault nurse examiner. Through this role, she hopes to make a difference in the lives of sexual assault victims, helping them become less scared and more comfortable through the medical examination. She said she would like to share the same strength and comfort she received from her advocates in the Forte case.

For now, her day-to-day routine keeps her occupied. Besides working full time as an emergency room and transport nurse, she is busy building a new life with her husband and their five children, ranging in age from 10 to 21. Her days are punctuated by the children’s academic and extracurricular activities.

She also goes to church, prays before work and runs almost every day. She said running several miles each time helps provide some respite.

The day she learned of Forte’s death, Dinko said she ran for 10 miles. She felt sad at the beginning of the run, angry toward the end, but enjoyed a moment of peace in between.

“I think of nothing,” she said. “I just run, and it feels good.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled Craig Whitney’s last name in a photo caption.