As Vermont’s Climate Council prepared to deliver the state’s first Climate Action Plan last fall, its most impactful recommendation — the multi-state Transportation Climate Initiative Program — fell apart. In its absence, state officials are counting on a proposed “clean heat standard” to quickly and effectively lower the state’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The clean heat standard is one of more than 200 recommendations included in the council’s plan, but it’s expected to significantly reduce emissions in the thermal sector, whose emissions are topped only by transportation.

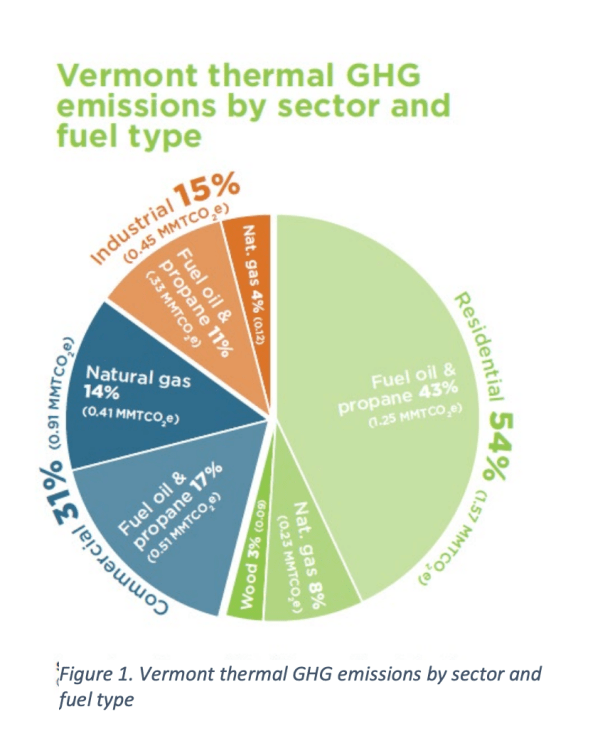

About 34% of Vermont’s total greenhouse gas emissions come from the heating sector. Vermont’s 2020 Global Warming Solutions Act requires the state to measurably reduce those emissions, and reductions in each sector must be proportionate to the amount the sector produces.

In the thermal sector, Vermont must reduce emissions 15% by 2025, 40% by 2030 and 80% by 2050.

Lawmakers are using a whitepaper, authored by climate council members and a working group focused on clean heat, to craft legislation, which would eventually be implemented by the Public Utility Commission. The whitepaper articulates the stakes of creating a well-functioning program.

“Unless we rapidly revamp the heating sector we can’t come close to meeting Vermont’s climate goals,” it says.

How it would work

So, under the proposed legislation — still a work in progress — what would a clean heat standard look like?

The goal is to incentivize and regulate the reduction of fossil fuel emissions that come from heating buildings across the state. It’s similar to the state’s renewable energy standard, which started in 2017 and required Vermont utilities to slowly transition to renewable energy. A clean heat standard would be implemented and regulated through the state’s Public Utility Commission.

Obligated parties — more on them later — would need to prove that they’re contributing to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by a set amount each year, starting in 2024. They’d do that through a credit system.

A clean heat credit, according to a bill drafted by the House Committee on Energy and Technology, is a “tradeable, non-tangible commodity that represents the amount of greenhouse gas reduction caused by a clean heat measure.”

Fuel providers could switch out the higher-emitting fossil fuels for lower-carbon options, such as biofuels or renewable natural gas. Or, they could help install systems like cold-climate heat pumps and advanced wood heating systems, like pellet stoves.

Obligated parties would be required to obtain a certain number of credits each year, and that number would rise gradually over time. They could reduce emissions in a number of ways: by delivering clean, low-carbon heat directly to homes; through contracts with delivery companies that deliver the clean heat options; through the market purchase of clean heat credits; or, according to a draft bill, “through delivery by an appointed statewide delivery agent.”

Not all fuel dealers are obligated parties, but anyone who delivers those “greener” options to Vermont homes could receive credits, “which could then be sold to the upstream fossil fuel providers who will need them to meet their annual performance obligations,” the whitepaper says.

Some environmental activists who have long been watching regulation around fossil fuels develop in the state say they’re concerned that considering certain fuels “clean” could be misleading.

Julie Macuga, formerly the co-director and fossil fuel resistance organizer for 350VT, sent a letter to the committee imploring members to look further into “renewable natural gas,” which she said takes up a small fraction of natural gas in the state and would be hard to scale up.

A snag

The House Energy and Technology committee recently discovered a significant snag: Originally, Vermont’s smaller, independent heat distributors would not have been considered “obligated parties.” Those businesses would have earned credits by delivering cleaner solutions, and could sell the credits to the obligated parties: mostly large, wholesale businesses upstream.

But Vermont can’t regulate wholesale fuel distributors in other states. As many as 80% of Vermont’s small dealers purchase at least some of their fuel outside of Vermont, according to Matt Cota, the executive director of the Vermont Fuel Dealers Association.

In those cases, the obligated party would be “the entity that makes the first sale of the fossil-based heating fuel in the state for consumption within the state,” the draft bill says. That shifts much of the financial burden to “companies as small as a guy with a truck and a cellphone,” Cota said.

Lawmakers in the House Energy and Technology Committee expressed unease about that idea last week when they met to deliberate over the weeks’ worth of testimony they had heard on the clean heat standard.

“The obligated party question is the elephant in the room in terms of how we, first, better understand that, and then second, how we look at this legislatively to address concerns that we have there,” Rep. Tim Briglin, D-Thetford, told the committee, which he chairs.

Some small heat distributors are well-poised for the transition, and have already been folding clean heat measures — like heat pump installation and transitions to cleaner-burning fuels — into their business models, Cota said. Others aren’t as ready.

“I am concerned that there’ll be a lot of companies that won’t be able to make the transition and won’t be able to survive this transformation,” Cota said. Volatility in the heating business could have negative implications for Vermonters in winter, he said.

Equity

Legislators are also concerned about making the transition to clean heat accessible for all Vermonters, including those with low incomes.

The draft legislation would require fuel companies to source “a substantial portion” of clean heat credits from services — one third of the total requirement — to low-income households.

Rebecca Foster, acting director of Efficiency Vermont, told VTDigger the organization is pushing the legislature to implement a standard that would keep “Vermont’s heat affordable, and in fact, would increase affordability,” she said.

“We know it’s really expensive for a lot of people, taking up about 35% of families’ energy budget in the state,” she said.

The legislature didn’t set up the Public Utility Commission to have specific expertise in creating equitable programs, Rep. Lucy Rogers, D-Waterville, told the House Energy and Technology committee.

Briglin said the committee should interrogate the issue further.

The House Energy and Technology Committee plans to take additional testimony on the draft legislation in the coming weeks.

Correction: An earlier version of this story gave an incorrect name for the House Committee on Energy and Technology in one instance.