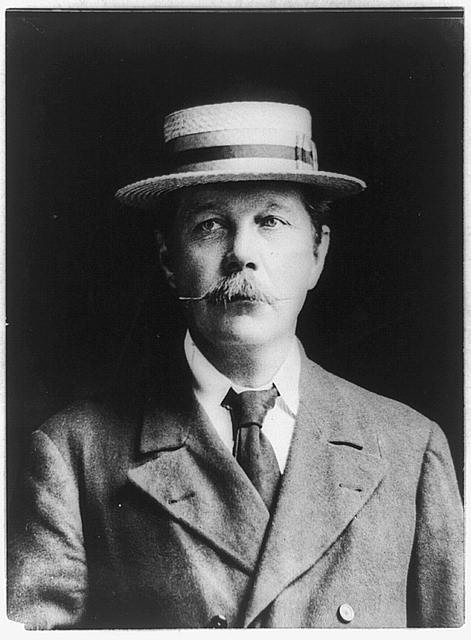

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was no Sherlock Holmes. Where the fictional detective was detached and skeptical of taking things at face value, his creator was biased and easily duped.

Conan Doyle famously investigated claims that a pair of English schoolgirls had managed to photograph fairies in Yorkshire, and he declared the photographs authentic. The claim is astounding, at least to modern eyes, because the images are clearly of paper cutouts, not animate beings. But Conan Doyle was hardly alone in his belief. In the days before Photoshop, many people simply believed what they saw in photographs rather than their own common sense.

In a less well-known incident, this one centered in Vermont, the mystery writer came to the defense of a farm family said to possess amazing psychic powers. Conan Doyle’s support came in 1926 in his two-volume “The History of Spiritualism,” published a half-century after the Eddy family gained international renown as spiritual savants.

Conan Doyle visited Vermont during the early 1890s to see a friend, writer Rudyard Kipling, in Dummerston. The two played golf and Conan Doyle brought Kipling a pair of skis, in hopes the outdoorsy Kipling would take up the new sport.

It was perhaps during that visit to Kipling that Conan Doyle first learned of the Eddy family, though he apparently never met any of them. Still, he definitely read, and perhaps also heard, plenty about them.

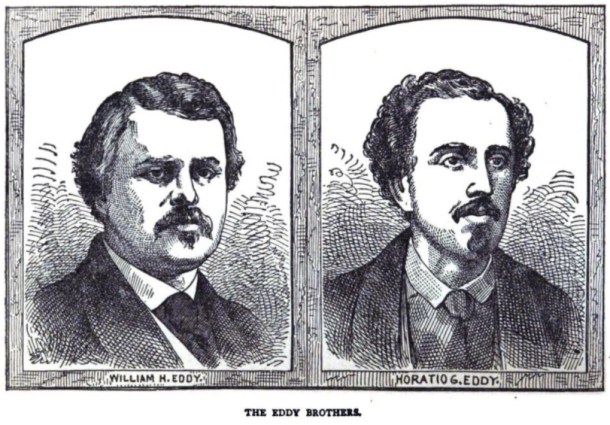

Three decades later, when he published his book on spiritualism, he wrote that “(t)he Eddy brothers, Horatio and William, were primitive folk farming a small holding at the hamlet of Chittenden, near Rutland, in the state of Vermont.”

Another writer who knew the Eddys described the brothers similarly: “(They are) sensitive, distant and curt with strangers, look more like hard-working rough farmers than prophets or priests of a new dispensation, have dark complexions, black hair and eyes, stiff joints, a clumsy carriage, shrink from advances, and make newcomers feel ill at ease and unwelcome.”

Still, despite their off-putting demeanor, the brothers attracted visitors from around the world. Their ordinary farmhouse in rural Chittenden was said to be the site of otherworldly phenomena.

Six nights a week

Six nights a week, William and Horatio Eddy demonstrated their skills as mediums to the many people who traveled to Chittenden. Among those who made the journey was Madame Helena Blavatsky, the Russian mystic, medium and author who would go on to found the religion of Theosophy.

While the brothers didn’t charge admission to their seances, they did turn their farmhouse into an inn, charging fairly high prices for quite basic accommodations. As Conan Doyle described it, the Eddys offered guests lodgings in a “great room with the plaster stripping off the walls and the food as simple as the surroundings.”

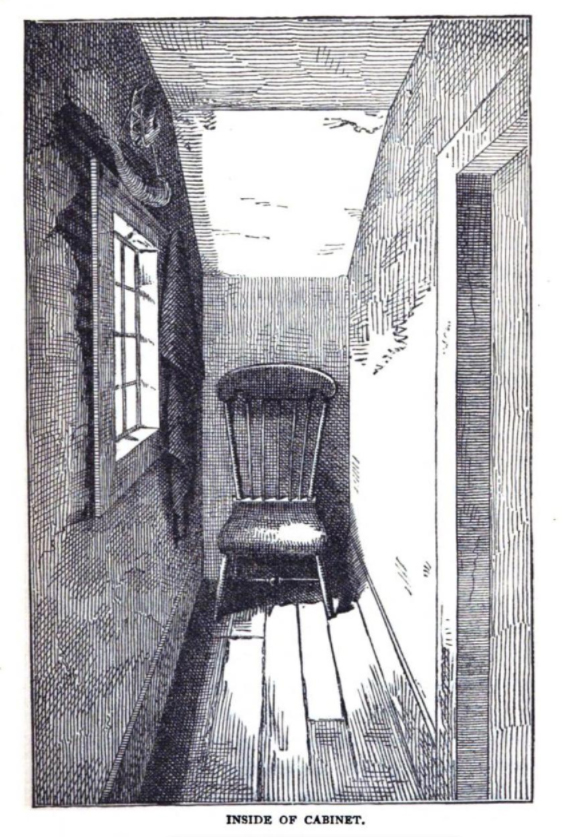

The Eddys’ demonstrations featured musical instruments that seemed to float in the air and hands of various skin tones that appeared above a curtain, suggesting that the room was filled with spirits of different races. The most sensational part of the show came when William would leave the stage, which was located in a large, dimly lit room in the farmhouse, and retire to his “spirit cabinet.”

The cabinet was a small room to one side of the stage with a chair and a window to the outside. Soon after he entered the cabinet, William would seem to conjure an array of spirits that emerged from the cabinet to take their turn upon the stage.

It was a strange cast — Native Americans and Africans, a mother and child, a salty sailor, a young girl and countless others — all said to be the spirits of the dead. The spirits never appeared in bright light, Conan Doyle explained, because “(w)hite light … has been found to prohibit results, and this is now explained from the devastating effects which light has been shown to exert on ectoplasm.”

Ectoplasm, Conan Doyle and others believed, was the material form spirits took when summoned by mediums. The Eddys were said to have tried many different-colored lights, but found the spirits could tolerate only red.

“In the Eddy séances. there was a subdued illumination from a shaded lamp,” Conan Doyle wrote. That single light source, according to some descriptions, was nearly 30 feet from the stage.

One figure who emerged regularly was an American Indian woman named Honto, “who materialised so completely and so often that the audience may well have been excused if they forgot sometimes that they were dealing with spirits at all,” Conan Doyle wrote.

Pretty realistic

The spirits demonstrated other traits you might more readily associate with living people. Audience members sometimes managed to touch the spirits, though they reported that the figures felt cold and clammy; spirits’ lips moved when they spoke; and when their breath was exposed to lime water (calcium hydroxide), the solution turned milky, proof that these beings exhaled carbon dioxide.

But Conan Doyle’s belief was unshakable. He noted that many powerful forces were allied against spiritualism — the clergy, leading scientists and “the huge inert bulk of material mankind.” These forces had so dominated the debate over spiritualism that “everything that was in its favour was suppressed or contorted, and everything which could tell against it was given the widest publicity.”

People had trouble accepting spiritualism, he wrote, because “such phenomena … seemed to be regulated by no known law, and to be isolated from all our experiences of Nature.”

Biographers attribute Conan Doyle’s tenacious belief in spiritualism to a series of tragedies that befell the author. His wife died in 1906, followed by his son during World War I. He also lost a brother, two brothers-in-law and two nephews during that period. Overwhelmed by grief, Conan Doyle wanted hope that he could reconnect with his dearly departed.

The Eddys had their own back story, of course. The brothers’ parents, Zephaniah and Julia Ann MacCombs, moved to Chittenden in the late 1840s after selling their farm in Weston. Julia Ann had a reputation as a clairvoyant who could predict the future and converse with unseen spirits. People said she got the gift from her great-great-great-grandmother, who purportedly was tried and sentenced to death as a witch in Salem, Massachusetts. (In one version of the story, the condemned woman managed to escape and sail back to her native Scotland.)

Zephaniah was apparently more than a little disturbed by his wife’s behavior. His concern only grew when he realized that some of his 11 children — most notably William and Horatio — also exhibited supernatural traits. While the children slept, they would supposedly disappear from their cribs or beds and reappear in other parts of the house.

William and Horatio proved disruptive at school. Their desks would make strange knocking sounds and seem to levitate. Other times, books and slates would fly from the boys’ hands. At home, Zephaniah said he saw his boys playing with friends or doing chores with others, but found that the figures would disappear whenever he approached.

Some of the Eddy children were said to fall into trances that infuriated Zephaniah, who tried to rouse them by dousing them with boiling water. Conan Doyle quoted a source who claimed to have seen marks on the grown Eddy children.

During the mid-1800s, spiritualism became a public frenzy as people sought ways to bridge the gap between the living and the dead. The movement started when word spread that the girls in the Fox family of upstate New York could communicate with the dead, who responded to questions with knocks.

On tour with their father

The public’s rising interest in the occult gave Zephaniah an idea. For 15 years, he toured several of his children in the United States and Canada, and even sent them briefly to London. Skeptics suggested Zephaniah had manufactured the stories of his offspring’s strange childhoods as a marketing ploy.

After Zephaniah’s death in 1862, the grown Eddy children returned permanently to Chittenden, but continued performing. The shows gained Chittenden the nickname “Spirit Capital of the Universe.” Among the Eddys’ visitors was journalist and lawyer Henry Steel Olcott, who had been one of the investigators into President Lincoln’s assassination.

Olcott, a purported skeptic, stayed in Chittenden one summer and attended the almost nightly seances, where by his count he witnessed 400 different spirits emerge from the cabinet. Olcott watched the demonstrations, studied the Eddy house and interviewed townspeople, but never found any hokum in the seances.

In fact, Olcott became such a believer in spiritualism that he helped Blavatsky found the Theosophical Society.

Other skeptics, however, publicly debunked Eddy’s shows. William Ellsworth Robinson, who performed under the stage name and persona of a Chinese magician, Chung Ling Soo, detailed how the brothers used sleight of hand to make it appear that they were levitating musical instruments. (Robinson would die onstage when one of his own illusions — of seeming to catch a bullet in his hand — went awry.) Other aspects of the Eddys’ performances were also explained in a book by debunker John W. Truesdell with the marvelous title “The Bottom Facts Concerning the Science of Spiritualism.”

Conan Doyle, however, sided with Olcott’s view of the Eddys. His belief in spiritualism was absolute.

When one of the Fox Sisters recanted her claims of special powers and demonstrated how she had fooled observers, Conan Doyle’s faith remained unshaken.

“Nothing that she could say in that regard would in the least change my opinion,” he wrote, “nor would it that of anyone else who had become profoundly convinced that there is an occult influence connecting us with an invisible world.”

Presented with the same evidence, what would Sherlock have said?