For years, the K-6 students at Westminster Center School had two lunch options: a sun-butter and jelly sandwich, or an entrée crafted from local food and created by Harley Sterling.

Sterling ran Westminster Center’s kitchen, pitching his healthy alternatives to kids wary of new foods. Some days, the students balked at his dishes, and Sterling’s patience faltered.

“There were definitely some times when you’d get, like, 10 or 12 kids in a row only taking sun-butter and jelly,” he remembered. “One day, I had a temper tantrum, and was like, ‘OK, you know what? We’re not going to serve sun-butter and jelly anymore. You can have a sun-butter-only sandwich.’”

The students have come to appreciate Sterling’s farm-to-table fare — and now more students are able to partake in it. He has since become the school nutrition director for the Windham Northeast Supervisory Union, spreading his local food initiatives districtwide. And thanks to a Vermont state law enacted this year, he’ll be cooking with more local foods than ever before.

Signed by Gov. Phil Scott in July, Act 67 created a pilot program that would temporarily establish a tiered incentive for public schools to purchase food from Vermont’s farmers: buy 15% local products, receive 15 cents back for every lunch served. The law also creates 20% and 25% tiers.

Sterling welcomed the incentive. “I’m super excited,” he said. “And I think that around the state there’s a lot of buzz.”

Last year, Windham Northeast spent roughly 20% of its $650,000 food budget on local products. Sterling hopes to reach that same level this school year.

Nutrition service directors, food distributors and politicians call the new law a win-win. They say cafeteria trays will feature healthier food, and Vermont’s farmers will develop increased, reliable sources of income.

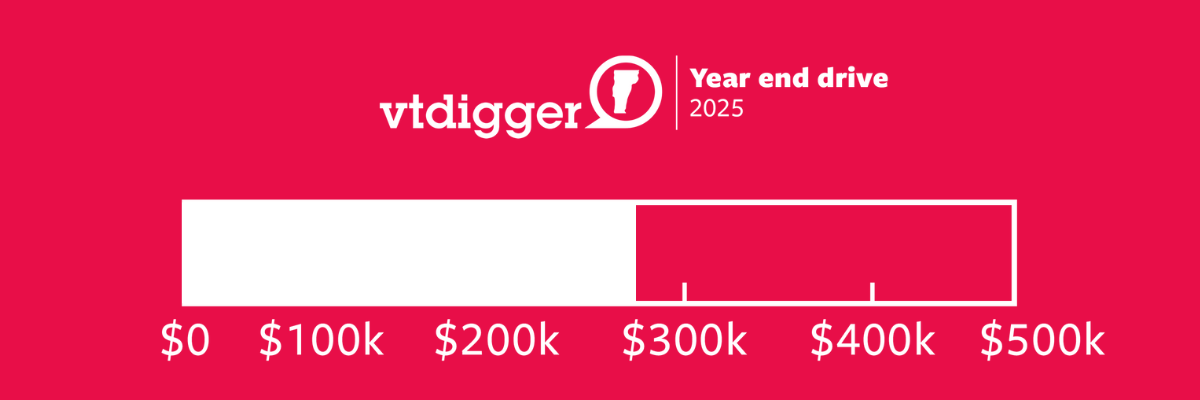

The Legislature has allocated $500,000 to reimburse schools this academic year as part of a pilot program. And for this year only, schools can receive 15 cents per lunch without reaching the 15% threshold. Instead, to qualify, districts must submit a local food purchasing plan, designate a staff member responsible for implementing it, develop a process for tracking local food purchases and comply with the state’s reporting requirements.

Sen. Chris Pearson, P/D-Chittenden, vice chair of the Senate Committee on Agriculture, said legislators modeled the new law on similar incentives in New York and Oregon.

“I believe many food directors would love to purchase more local food, but it can be more expensive than the food that comes in from big producers, commodity markets, etc.,” he said. “So we’re trying to acknowledge that cost and help schools meet it.”

Although the incentive is currently funded for one year, Pearson hopes for and anticipates its renewal. “I’d like to see it in a more permanent way so that schools can more readily depend on it,” he said.

During the 2020-21 year, schools received between $3.61 and $4 in combined reimbursement per free or reduced priced lunch, according to the state Agency of Education. But only $1 to $1.50 of that money goes toward buying food, said Helen Rortvedt, farm-to-school director at Vermont FEED, a Shelburne-based organization that has promoted such initiatives for over 20 years.

“You add 15 to 25 cents, and that makes a dent,” she said.

Food prices continue to rise, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture reimbursements have not kept pace.

“Schools have figured out what they can buy with their very limited budgets,” Rortvedt said. “The major barrier that continues to persist is cost.”

Betsy Rosenbluth, program director at Vermont FEED, stressed the importance of the connections between farmers and students that the new law will create. A 2014 report by the Vermont Agency of Education found that Vermont public schools spent $16 million on food each year. The more local food purchased, the more connections fostered between students and Vermont’s food systems.

Asked whether the local-food incentive would be fully subscribed in its first year, Rosenbluth replied, “I think it’s possible.”

But no one knows for sure what will happen. Before now, the extent of local-purchase tracking varied widely from district to district, as has each district’s definition of “local.” Now, schools must use the definition of local established by Act 129, which sought to standardize the term statewide. Whole foods must come from Vermont, or from within 30 miles of a school.

For border districts such as Windham Northeast, which includes schools in Westminster, Bellows Falls, Grafton and Saxtons River, Act 129’s definition of “local” changes the way nutrition directors must think about sourcing ingredients.

Sterling, the district’s nutrition director, has been forced to find new producers to hit the law’s thresholds.

“Ground beef is a very expensive, very big part of our program,” he said. “We make tacos, sloppy joes, shepherd’s pie. It’s a huge thing.” In previous years, Sterling has obtained beef from a Massachusetts farm 40 miles away. Now, he’ll switch to a Vermont farm.

The state’s food hubs appear to be prepared to help schools find products that fit the new law’s local definition. Food hubs aggregate foods from small- and medium-size farms, distributing to a wider market than most farmers can handle on their own. Food Connects, a food hub in Brattleboro, distributes food to 30 schools across Vermont and New Hampshire. All of the products it sells are source-identified, making it easy for schools to record and report their local purchases when it comes time to apply for reimbursement.

Tom Brewton, a local foods sales associate at Food Connects, has been working with school nutrition directors this summer to prepare for Act 67’s first year. “A lot of food service directors are just getting their feet wet with the verbiage of the act, and we’re trying to get ahead of that and assist our districts as much as we can with applying for the program,” he said.

In addition to supply chain support from hubs like Food Connects, the Agency of Education plans to hire an administrator to work directly with school nutrition directors.

Since taking over Windham Northeast’s food service operations in 2018, Sterling has become a statewide leader in bringing local food into the cafeteria. He plans to continue setting an example, reaching the new law’s highest tiers.

“I really want to show that it’s possible to hit that 20% or 25%,” Sterling said. “If we can do it, I think there’s a lot of people who can do it.”