We all now know what it’s like when a pandemic starts. But how does one end? Vermonters a century ago must have been pondering that question while they were enduring one of the worst pandemics in human history.

Even in the midst of our own pandemic, it is hard to grasp how frightening it must have been to live through the influenza pandemic of 1918. Often referred to as the Spanish flu, though it was first detected in Kansas, the disease would end up killing somewhere between 20 million and 50 million people worldwide in a little over a year. The Black Death might have killed up to 10 times as many people during the Middle Ages, but it took three centuries to do so.

During the spring and summer of 1918, a deadly influenza was circulating in Europe, perhaps brought by American troops shipping over to fight in the First World War. The disease reached New England in late summer, possibly again using troops as its host.

On Sept. 21, the Vermont Board of Health warned that the virus would soon arrive here and ordered local health officers to report any influenza cases. Three days later, Vermonters learned that 100 students at Norwich University and Middlebury College had contracted the disease.

Responding to the disease fell to local authorities. Charles Dalton, secretary of the Vermont Board of Health, said it was up to town health officers to decide whether to close schools, churches and other public gathering places. He said the state board was unlikely to issue a statewide ban.

Several days later, newspapers reported that one of the Middlebury students, a freshman named Charles Harold Thompson, had died. Thompson’s parents had traveled from their home in New Jersey when they learned their son was gravely ill, and were with him when he died in the early morning hours.

Tragic as it was, the news was hardly surprising. The disease was known to hit the young harder than older people. Looking at a graph of the total number of deaths by age group, one would typically expect a gradual rise as people age. But statistics for 1918 compiled by historian Michael Sherman show a disturbing double hump on the graph, with the number of deaths rising swiftly starting in the 5-to-10-year-old group and peaking among 25-to-30-year olds, before declining gradually and finally resuming the expected trajectory in the 45-to-50 age group.

Scientists still aren’t sure why the 1918 flu killed so many people in their prime. One theory is that these victims’ strong immune systems worked against them by going into overdrive to try to fend off the novel virus. Doctors desperately tried to save victims, but they had no effective tools: No vaccine to prevent contagion and stop its spread, and no antibiotics to treat the potentially lethal pneumonia that often followed.

The most effective defense seems to have been social distancing. With the decision whether to close down being a strictly local judgment, communities across the state started shutting down in a patchwork pattern. St. Johnsbury banned all public meetings. Schools closed in Barre, Brattleboro, Montpelier, Randolph, St. Albans and Wells River. Meanwhile, the state Supreme Court postponed the start of its session, the state Republican Party postponed its convention, and many businesses, some experiencing a 50 percent sick rate, struggled to stay open.

Obituaries and other influenza-related news filled newspapers. The disease hit some communities hard while leaving others virtually unscathed.

The hardest hit was Barre. Over one particularly brutal five-day stretch, from Sept. 28 through Oct. 2, doctors reported 39 flu deaths in the city.

The state steps in

The situation was so dire that, on Oct. 4, the state board of health reversed course and intervened, ordering all of Vermont’s schools, churches and theaters closed, and prohibiting public gatherings. On Oct. 7, an estimated 10,000 Vermonters, out of a population of 350,000, had the flu. A week later, the estimate rose to 15,000.

The restrictions seemed to work. As quickly as case numbers had risen, they began to fall. By mid-October, newspapers reported that communities around the state were on the mend. On Oct. 31, the state board revoked its ban on public gatherings.

The announcement lifted the pall that had shrouded daily life in Vermont. The public’s sense of relief was only heightened 11 days later, when world leaders signed an armistice ending World War I. People felt like the bad times were over and they could have their lives back. If they still thought about the pandemic, they didn’t talk about it much.

Today, when the Spanish influenza pandemic is recalled, many people assume it wrapped up neatly in the fall of 1918. In reality, although the worst was over, the pandemic hadn’t ended.

Health officials in St. Albans noticed a spike in cases starting on Dec. 3. By the last week of December, they were worried enough that they ordered the city’s schools, churches and some businesses closed.

In Lincoln, the local board of health decided on Dec. 30 to close the town’s schools and churches indefinitely. The Vermont Board of Health dispatched a doctor to care for the sick in Lincoln and neighboring Bristol Notch, because two local doctors had fallen ill with the flu.

Vermont closed out 1918 with an official death toll from influenza of 1,772, though the actual number might have been higher. The tally relied on local doctors accurately determining the cause of death and reporting their findings to the state.

By Jan. 1, 1919, the number of influenza cases varied widely across Vermont, as did local responses. Sometimes even the responses within a single community were inconsistent. On New Year’s Day, the Brattleboro Daily Reformer reported that a group of Masonic groups had canceled their joint holiday party, but the regular meeting of the local Masonic council scheduled for Jan. 2 was still on.

In general, the situation in Brattleboro seemed to be improving. The Reformer reported elsewhere in the Jan. 1 paper that the local health officer had received no new reports of flu in town that day: “The outlook in the influenza situation is more favorable today than at any time since the disease made its second appearance, Dec. 14.”

Things weren’t looking as good in Burlington. On Jan. 2, the Free Press reported that 30 cases had been identified locally in the last several days. The city had also experienced flu deaths, the most recent being that of Ida May Bailey, a waitress at the Vermont Hotel. “While conditions grow better in one community, they grow worse in another,” the paper noted.

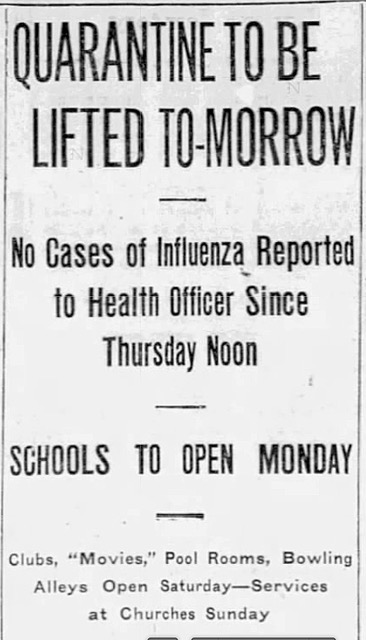

As conditions in Burlington worsened, they were improving in St. Albans. “(E)verything will be wide open again to-morrow,” the St. Albans Daily Messenger announced on Jan. 3. That meant that churches, movie theaters, billiard rooms, bowling alleys and, perhaps most importantly, schools could reopen. The toll from the local December outbreak was five deaths.

“The ban has interfered in one way quite seriously with the mercantile life of the community, and there will be satisfaction that the time has come when it can be removed,” the Messenger said. “…The health authorities believe that the ban has been instrumental in eliminating the menace of a recurrence of the disease in epidemic form.”

The newspaper urged readers to remain vigilant. “Individual responsibility is still being stressed by the health officers,” the Messenger said. “People should continue to exercise due precautions, to avoid as much as possible crowds, and sneeze and coughs should be smothered. People should live the life that gives them the maximum resisting power to the disease, get sufficient rest and not overtax their physical resources.”

The surge in cases that started in December was declining by the end of January. On Feb. 5, the state board of health reported 698 new cases for the previous week. That was down significantly from recent weekly totals that had ranged between 1,200 and 1,300.

Tragedies not over

The improving numbers masked the individual tragedies still taking place. “Three popular young people” from Wardsboro had died since Christmas, the Orleans County Monitor reported. They were Mr. and Mrs. J.E. Coleman, who ran a local hotel, and Perley Kidder, the postmaster. The Bristol Herald reported on Jan. 9 that pneumonia triggered by influenza had killed Irene Jacobs. She was 14 years old.

When 24-year-old Helena May Cameron died on Jan. 11, the Rutland Daily Herald noted that she was the fourth member of her immediate family to die from the flu in the previous two months. These deaths, coming when the end of the pandemic was in sight, must have borne an extra tinge of tragedy, like the deaths of soldiers after the armistice was declared.

February brought news that the pandemic seemed to be losing its grip on Vermont. The state was now seeing about 300 new cases a week. Still, small outbreaks continued. A cluster of new cases emerged in late March in southeastern Vermont, particularly in Springfield, Bellows Falls and Brattleboro. Springfield officials responded by closing schools a day early for spring vacation and persuading churches to cancel services for one Sunday. The state board of health ordered the movie theater in town closed.

Statewide, the numbers kept improving. Only 171 new cases were reported for April, though newspapers still reported occasional updates of additional flu-related deaths. Among the dead were 19-year-old Marion LeBoeuf of Vergennes, who died from a lung ailment after contracting the flu, and 24-year-old Ray Alonzo Bellows of St. Albans, who had survived a bout of flu, which he caught while serving in the Army, but succumbed to pneumonia after being discharged home to convalesce.

Eventually these death notices became rare as the pandemic burned itself out. In all, influenza claimed almost 400 lives in Vermont in 1919, bringing the total number of deaths for the pandemic to more than 2,100.

Subtle clues on normalcy

Because the state largely left it to local communities to impose restrictions, there was no moment when Vermonters were told they could return to their regular lives. The clues that normal life was returning were more subtle.

Starting that summer, when newspapers reported on the state board of health, influenza became almost a footnote, just part of a list of diseases the board was concerned about, listed alongside whooping cough, scarlet fever, mumps and other maladies.

The board made more news when it flagged the milk-handling practices of some dairies as unhealthy, and when it opened a free clinic in Burlington to treat venereal diseases.

Soon the main reminder of the flu that Vermonters saw in their papers were the regular advertisements for patent medicines making dubious medical claims. Ads for Dr. Henry Baxter’s Mandrake Bitters, which ran almost daily in the Free Press, warned readers that “the germs are in the very air we breathe and a good laxative-tonic is the best preventative.”

The ad stopped running in August. Perhaps that was the signal that the pandemic was really over.