For a scientific man, Peter Kalm sometimes had an odd way of marking distance. In his journals from his 1749 journey along Lake Champlain, he wrote that Fort St. Frederic was “about a musketshot” from the opposite shore, now known as Chimney Point in Vermont.

The measurement was inexact, to be sure, but apt. Kalm was visiting an area in tumult. The Dutch, British and French were battling each other and the native Iroquois and Abenaki peoples along often nebulous borders for control of the region.

What was a highly educated Scandinavian scientist like Kalm doing in the midst of this skirmish? He was in North America at the behest of his mentor, the famed scientist Carl Linnaeus, who wanted Kalm to search for plants that would benefit Swedish industry. It was Linnaeus, a botanist and zoologist, who devised the system for naming and categorizing types of plants and animals.

That Kalm would come to work with the likes of Linnaeus was hardly evident from the circumstances of his birth. Kalm was born in Sweden, to which his parents had fled after war erupted in their native Finland. His father, a clergyman, died when Kalm was only 6 weeks old. Several years later his mother moved the family back to Finland, where the boy grew up in poverty.

But Kalm managed to get an education, and his keen intellect caught the eye of a wealthy baron who was also a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. The baron hired Kalm to oversee his experimental plantations and helped him enroll at the University of Uppsala in Sweden. At the university, Kalm studied under Linnaeus.

In 1748, at age 32, Kalm sailed for Philadelphia as the leader of a Swedish scientific expedition. He met some of the leading scientific minds in the Middle Colonies, including Benjamin Franklin.

Swedish officials wanted Kalm to focus on Canada, since its climate was thought to be similar to their own country’s. As he traveled north from New York, Kalm left behind civilization as he knew it. Along his route to and from Canada, he would travel the length of Lake Champlain twice.

His first extended stopover was at Albany, New York, which was then a crude wilderness outpost. Kalm studied the area’s plant life, but was disgusted by what he saw of its human life. He wrote that the Dutch settlers displayed “avarice, selfishness and immeasurable love of money.” Kalm said that the Dutch purchased booty from the just-completed King George’s War, “silver spoons, bowls, cups, etc. of which the Indians robbed the houses in New England … though the names of the owners were engraved on many of them.”

As his party moved north from Albany, Kalm witnessed signs of failed efforts by Europeans to tame and claim the wilderness. At Saratoga, he saw the burned-out remains of a British fort that the British themselves had torched two years earlier to keep it out of French hands. Soon, Kalm’s party passed the ruins of a trading post that had been burned four years earlier by the French and Indians. Heading north from Fort Anne, they crossed paths with a group of six French soldiers from nearby Fort St. Frederic at Crown Point, who were escorting several Englishmen to Saratoga.

The Frenchmen warned Kalm and his party to wait until they could arrange a military escort north — a group of six Indian warriors was known to be in the area seeking revenge for the death of one of their own. Kalm dismissed the Frenchmen’s concerns and pushed on north, making it safely to Fort St. Frederic. There he found a surprisingly peaceful scene. Kalm couldn’t have known it, but he was there during a five-year lull in the seemingly ceaseless North American wars.

French soldiers, who had been paid off when King George’s War ended the previous year, had built crude cottages on land they were granted surrounding the fort. The men lived in meager wooden huts that reminded Kalm of poor parts of Sweden. Unlike Swedish peasants, however, these people had plenty of food, he noted.

Three days after arriving at Fort St. Frederic, Kalm and the others saw the Indian party they had been warned about. While at dinner, Kalm heard a distant “bloodcurdling outcry.” The fort’s commander feared it meant the Indians had exacted their revenge. From a window, Kalm saw them paddling a boat, at the front of which stood a long pole with a bloody scalp atop it.

“They were dressed in shirts, as usual,” Kalm wrote, “but some of them had put on the dead man’s clothes; one his coat, the other his breeches, another his hat, etc. Their faces were painted in vermilion, with which their shirts were marked across the shoulders.”

Inside the boat was an English boy of about 9, whom the Indians were taking north to Canada to join their tribe and take the place of their dead friend. (The boy, Enos Stevens, who was seized at Fort No. 4 in Charlestown, New Hampshire, was later released and returned home.)

Despite the fearsome sight, Kalm and his party ventured out regularly from the fort, crossing sections of the lake and exploring the surrounding countryside. From a height in the Adirondacks, Kalm observed what are known today as Vermont’s Green Mountains. “On the eastern side of this lake is (a) chain of high mountains,” he wrote. “Those on the eastern side are not close to the lake, being about 10 or 12 miles from it. The country between them is low and flat, and covered with woods, which likewise clothe the mountains, except in such places as the fires, which destroy the forest here, have reached and burnt them down.”

Later he noted that the Green Mountains consist of “high mountains, which are to be considered as the boundaries between the French and English possessions in these parts of North America.”

During his travels on Lake Champlain, Kalm reported regularly seeing Native Americans, whom he said came to the lake to hunt or fish for sturgeon. “These Indians lead a very singular life,” he wrote. Their diets changed by the season, centering on corn, beans and melons one season, then fish or wild game the next.

At the northern end of the lake, he encountered three Abenaki women in a canoe hunting ducks with a gun. “The women who had come hither had their funnel-shaped caps, trimmed on the outside with white glass beads,” he wrote. They also wore French women’s waistcoats and jackets.

Kalm was finding little in the natural world that surprised him, but he did learn that Indians were using a plant root to treat venereal diseases. Patients were “‘radically’ and perfectly cured within five or six months,” Kalm wrote. The French, who relied on Indians for the treatment, were unaware what type of plant was used, but Kalm learned it was Lobelia roots. (He would later report this treatment in an address to the Swedish Academy of Sciences. This connection with the treatment of venereal diseases explains why one species of the plant is known as Lobelia siphilitica.)

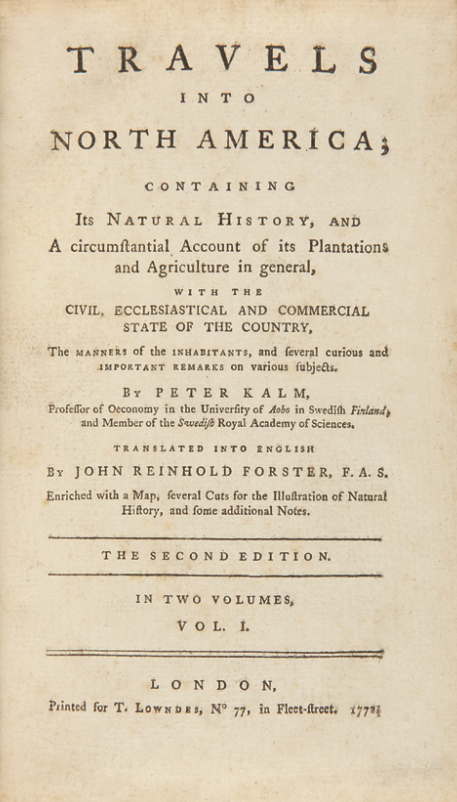

Kalm’s plans to travel deep into Canada were blocked by French officials, but he did manage to become the first scientifically trained person to observe Niagara Falls. Kalm’s journey through our region was something of a bust from a scientific standpoint. “In Lake Champlain,” he wrote, “I did not see anything that was new to me, neither plants nor anything else floating in it.”

An English translation of Kalm’s journals wasn’t published until more than two decades after the scientist’s visit. Benjamin Franklin was not impressed. He complained that Kalm had misattributed “idle Stories” to “Persons of Reputation,” presumably himself, and had changed the details of stories Franklin actually did tell him “so that I have been asham’d to meet with some mention’d as from me.”

“It is dangerous Conversing with these Strangers that keep Journals,” Franklin grumbled.

Franklin might have had cause for personal complaint, but in terms of collecting and preserving vivid images of a turbulent era, Kalm’s journals are invaluable.