When William Paul Dillingham became governor of Vermont in 1888, he focused his administration on one of the most pressing concerns of the day — the state’s stagnating population numbers.

He was hardly the first Vermont politician to flag this issue. Ever since there was such a thing as “Vermont,” its leaders have worried about the state’s population.

Dillingham came up with a novel way to address the issue. His approach, however, failed to meet its goals, and demonstrated the prevailing prejudices of Vermont leaders at the time.

It is no surprise that the state’s population drew Dillingham’s attention. For decades, Vermonters had been leaving in droves and new arrivals were hardly making up for the losses. Between 1880 and 1890, the state’s population rose by a scant 136 residents at a time when the U.S. population grew 25 percent.

The flat population numbers were mirrored in the state’s economy. After the Civil War, an economic malaise infected Vermont and the state couldn’t shake it. Young men, viewed by civic leaders as the future of their communities, often headed elsewhere for jobs, cheaper land and a more forgiving climate.

Some political leaders claimed that Vermont farmland was being “abandoned,” though there is no evidence people simply walked off their land without compensation. While Vermonters at the time fretted that the state was losing its best and brightest, some historians have since argued that many of those who left lacked the skills needed in Vermont’s changing rural economy.

Dillingham didn’t give himself a lot of time to tackle the population issue; he planned to follow the tradition of Vermont governors and leave office after a single two-year term. So his response to the state’s languishing population numbers took up much of his administration — and would take about a quarter of his farewell address when he left office.

Dillingham was in a bind. Vermont was having trouble enticing other Americans to move here, so if the state wanted to grow, it needed to encourage foreign immigration. But Dillingham was fiercely anti-immigrant, or at least fiercely opposed to certain kinds of immigrants. He declared that Vermont couldn’t continue to depend on its existing “foreign-born population to maintain the number of our farmers.”

By “foreign-born,” he meant the state’s French-Canadian and Irish populations. At the time, about one-third of Vermonters were either first- or second-generation French-Canadians.

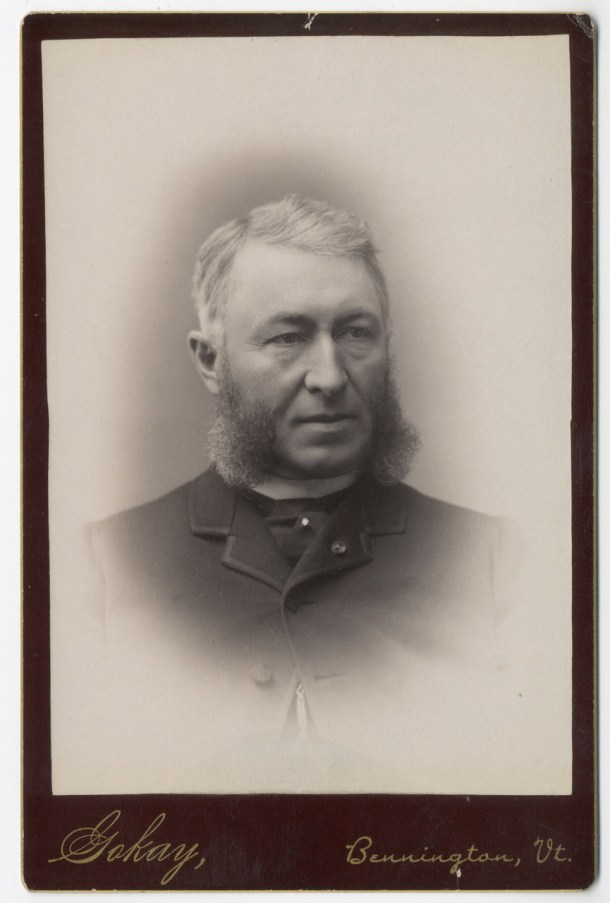

To address the population issue, the state Legislature created the Commission on Agricultural and Manufacturing Interests. To run the commission, Dillingham picked Alonzo Valentine, a Bennington mill owner and president of the Bennington County Savings Bank who had recently been elected to the state Senate.

Valentine said he knew the solution to Vermont’s perceived population woes: Swedes. Based on his experience meeting immigrants while he traveled around the American Midwest and West, Valentine was sure that Swedes had the values Vermont leaders were looking for and would fit in easily.

Valentine said Swedes came from a similar climate, were “well educated and hasten to have their children attend school where English only is spoken.” They were also “hardworking,” “honest,” “temperate in their habits and are religiously inclined.”

And that religion was Protestantism. Not coincidentally, Dillingham and other state leaders were also Protestants, and they were distrustful of Catholics, who they feared owed their allegiance first to the Vatican. That prejudice explains why Vermont leaders didn’t turn to Catholic French-Canadians and Irish people to bolster the state’s population.

Swedes had another thing in their favor: They were northern Europeans. State leaders shared a prejudice against southern Europeans, who they viewed as less hardworking and honest than Scandinavians.

‘Wrong’ sort of immigrant

Dillingham was hardly the first Vermont leader to believe in believing in the superiority of white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants. While the opinion was not universal, such attitudes dated back to the state’s founding. The Constitution required that legislators “profess the Protestant religion.”

During the mid-1800s, the fear of some immigrants in Vermont was couched in terms of disease, both literally and figuratively. After a cholera outbreak hit Burlington in 1849, authorities said immigrants — by which they primarily meant Irish Catholics — were “a cause of sickness, and a source of danger to the public health.”

In 1856, Gov. Ryland Fletcher, a member of the Know-Nothings, a new anti-immigrant party, said immigrants brought with them the “mortal disease (of) monarchy and despotism, of Romanism and heathenism, which left unchecked would sweep away our most cherished liberties and dearest institutions.” A branch of the Know-Nothing Party, the American Party of Vermont, called on foreign governments to stop deporting “paupers and convicts to our shores.”

George Perkins Marsh, the former diplomat and pioneering environmentalist, also feared the effects of immigration. Marsh wanted to ban or at least restrict the rights of immigrants to become naturalized citizens and declared that “our liberties are in greater danger from the political principles of Catholicism than from any other cause.”

Judaism also came under attack. After the Statehouse burned in 1857, Speaker of the House George Grandey opposed a proposal that the capital be moved to the more cosmopolitan city of Burlington. A one-time member of the Know-Nothings, Grandey dubbed Burlington the “great JEWrusalem of Vt.”

Even Vermont’s longtime U.S. Sen. Justin Smith Morrill feared the effects of immigration on American society. Immigrants, he believed, were bound to harm efforts to promote “republican institutions, higher wages, land homesteads, universal education.”

Morrill said immigrants often inhabited “the most inferior and wretched abodes in cities,” and suggested they preferred these conditions, since, he believed, they would “not accept of healthy and prosperous homes elsewhere.”

Despite Morrill’s comments, he helped create public land-use colleges and universities, which increased access to higher education for the general public, and specifically protected access for African Americans.

A ‘desirable’ sort of immigrant

Dillingham and Valentine were focused on Swedes, because they reminded them of the state’s best-known founders, and no doubt of themselves. If Vermonters were leaving the state, who better to replace them than people with similar characteristics?

Valentine praised the Swedes as different from the “vicious and undesirable classes of other lands.” While a Swede was indeed a foreigner, Valentine said, he was “our cousin with like instincts of freedom, secular and religious.”

Incidentally, Valentine wasn’t the first Vermonter to look specifically to Swedes to replace departing Vermonters. Redfield Proctor, the marble magnate from the town that now bears his name, made a change in his hiring practices during the 1870s, ordering his agents in large East Coast cities to give preference to Swedish workers over men from Ireland or southern or eastern Europe.

A Pittsburgh newspaper mocked Valentine’s plan, suggesting that Vermont should look in a different direction for new residents. Since the state “has always been so devoted to the colored race, and radical in maintaining their ‘rights’ and asserting their ‘equality,’” the Daily Post wrote, Vermont should instead recruit African Americans to move north from North Carolina “to fill the vacant farms of the Green Mountains.”

The newspaper was referring to Vermont’s being the first state to outlaw adult slavery in its constitution and its support of abolition in the run-up to the Civil War. But the Daily Post wasn’t sincere in its proposal. Reflecting the bigotry of many Americans of the period, the paper stated that “the negroes, the French Canadians, the Italians, Hungarians, Polanders, Bohemian, Russians, and of course Chinese” couldn’t meet the “requirements of a thrifty and pushing community.”

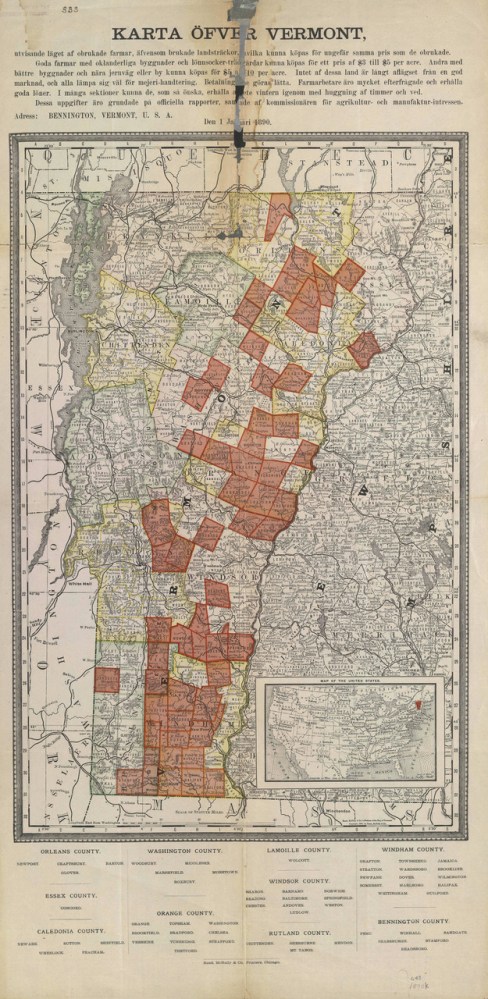

The Commission on Agricultural and Manufacturing Interests sent maps of Vermont to Sweden, advertising the availability of cheap land. Critics said the commission’s materials inadvertently led people to believe Vermont was something of a wasteland. Indeed, the St. Louis Register said the map highlighted Vermont’s “desolate regions.”

In his farewell address, the governor explained that he wanted to “induce the best class of Swedish emigrants to come to Vermont and settle upon what are known as unoccupied or abandoned farms, thus ministering to the wealth and prosperity of our State.”

For all Valentine’s efforts, few Swedes answered the commission’s call. The number is hard to pin down, but by Valentine’s count, 27 Swedish families, consisting of 55 individuals, arrived in April 1890.

Several Finnish families also made the journey. The families traveled from New York City to their new homes in the hill towns of Vershire, Weston and Wilmington. Dillingham greeted them enthusiastically and noted that “like our forefathers, they brought their pastor with them.”

A flawed plan

If luring Scandinavians to immigrate to Vermont proved popular among urban-minded policymakers, rural Vermonters remained skeptical. To hill farmers, this influx of foreigners did nothing to alleviate the concerns they felt; their children were leaving and their rural communities were feeling the strain.

Besides, they said, the plan was flawed from an economic point of view. One farmer at an 1890 meeting of the Vermont Dairymen’s Association explained that he had “no faith in our new craze” of reestablishing former farms. The properties, he said “had better be allowed to grow up to woods again than to try to make farms of them. I think the scheme a humbug.”

Other farmers echoed the sentiment, saying that some formerly cleared land was allowed to revert to woodlands for a reason: It wasn’t profitable to farm. One farmer predicted that “Swedes will do just as the Yankees do, work where they can get the most money.” This farmer proved prophetic. The Swedish arrivals didn’t suddenly restock Vermont’s population, or revive farms that Vermonters had found unprofitable.

Once in Vermont, Swedes tended to act like Vermonters. While some farmed, others accepted jobs in lumber mills and elsewhere. The Swedish colonies that Dillingham and Valentine envisioned failed to materialize, as the newcomers quickly blended into the surrounding communities, intermarrying with Vermonters, often the French-Canadians they were brought here to replace.

Despite the disdain for immigrants shown by some prominent leaders, over the years many Vermont communities did successfully incorporate people from an array of European countries. While the immigrants were often drawn by the need for skilled labor in mining and other industries, rather than the prospect of buying land, many Vermont communities slowly but surely assimilated new neighbors from countries including Italy, Scotland, Wales, Russia, Lithuania, Greece and Germany.

Overall, Vermont’s Swedish experiment had an unintended consequence. News reports about the novel plan helped publicize the availability of inexpensive land in the state. Soon wealthy people from out of state began buying up properties for second homes. This wasn’t the kind of growth Dillingham and Valentine were after, but it was a sort of immigration, even if it was distinctly part time.

Note: If you are interested in learning more, historian Paul Searls wrote extensively about the effort to bring Swedes to Vermont in his 2019 book “Repeopling Vermont.” The book explores the paradox of development efforts and examines other ways leaders have tried to revitalize Vermont.