This story by Madeline Clark was published by the Other Paper on July 16.

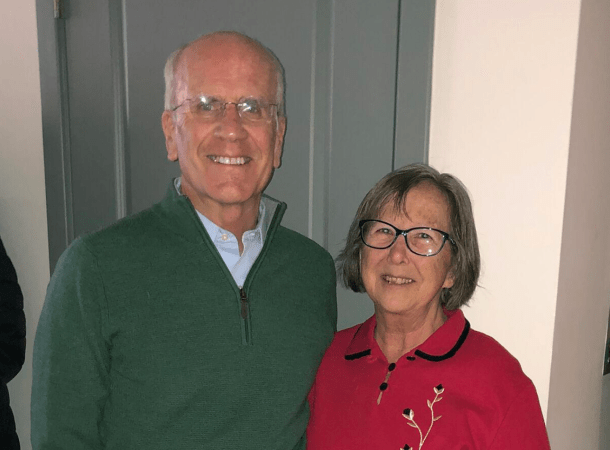

This fall, Pat Kilgour, 73, will celebrate her second year living at Allard Square, a senior housing development with affordable apartments in South Burlington.

And Kilgour thanks her lucky stars she is there — landing affordable housing was not easy.

She worked hard for 45 years of her life. While her housing costs meant she had to forgo things beyond her everyday needs, it was never an all-consuming concern.

But when Kilgour retired, Social Security became her sole income. At that time, Kilgour was 65 and had just settled into an apartment at The Pines in South Burlington. She received a modest tax credit to help with her housing expenses.

But it wasn’t long — about five years — until rent increases made her living situation untenable.

“I lived in constant worry,” Kilgour said.

Kilgour lived off ramen noodles and peanut butter sandwiches so she could afford her rent. She started to put off certain credit card bills. When her car failed inspection, she did not have the money to fix it.

She toured apartments that were “dumps” in her search for a less expensive home.

“I got afraid that I was going to be forced to move to a bad living environment to find someplace that might have lower rent,” Kilgour said. But even those places were unaffordable.

Kilgour’s luck turned around when she saw an article in The Other Paper about the groundbreaking of Cathedral Square’s Allard Square senior apartment building.

She wasted no time calling Cathedral Square to apply. But the nonprofit wasn’t accepting applications yet, instead they put her on an inquiry list.

Later, Kilgour was elated when she got the call that her application was accepted. But she still had no idea what her rent would be. The nonprofit lets apartments in a mix of market rate, tax credit and subsidized housing.

The uncertainty meant trying to make ends meet at her increasingly expensive abode and finding money for the move. Kilgour sold personal items, including her bed. She slept on her couch, awaiting the day she could move into Allard Square.

“When you are up against the wall, and you have no place to go and you’re 71 years old. It’s just like, ‘How can I afford a deposit on an apartment as well as the first month’s rent?’” she said.

Kilgour also had surgery during that time, adding to her expenses and making it impossible for her to pack and move her things on her own. She found volunteers to help pack and scoured the web for an affordable mover.

In October 2018, Kilgour moved into her new apartment and received a subsidy to help with the rent. The experience has been a humbling one, especially after working all her life, she said.

“It’s hard when you’re struggling because you don’t see a light at the end of the tunnel because literally, there is no place to go to,” Kilgour said. “When you see something like Allard Square, and such a waiting list, and you are accepted, it’s like somebody reached out and helped you when you were drowning.”

But Kilgour said she feels for those who haven’t been as fortunate.

She knows that there are multi-year waitlists at similar senior living facilities in the county and across the state. While she is grateful for Cathedral Square’s work, she said they can’t solve the affordable senior housing problem for all of Vermont.

Kilgour hopes the state can keep working to address the shortage. And she hopes it will keep people updated on that effort. She said she has already seen legislators like Rep. Peter Welch, D-Vt. — who toured Allard Square and met her in January — fight in Congress for those who need affordable housing.

On July 1, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the “Moving Forward Act,” which calls for a $100 billion investment into affordable housing infrastructure, among other measures.

“People do need to hear that their situation and their desperation is heard, and that they are aware of it, and that they are doing whatever they’re doing to give people hope,” she said.

Affordability crunch for senior housing

Since 1977, Burlington-based Cathedral Square has created affordable, “service-enriched” housing — most of which is for people aged 55 and older.

The nonprofit has about 1,000 apartments within 27 properties, and about 1,300 tenants, according to CEO Kim Fitzgerald.

Seventy-five percent of Cathedral Square residents live in subsidized housing, meaning they spend no more than 30% of their annual income on rent, Fitzgerald said.

But at about 1,200 people, the housing waitlist outpaces the number of rooms. The average wait is anywhere between three to five years, Fitzgerald said.

“It has taken us over 40 years to build or acquire the housing that we have currently, and I could literally build that tomorrow and not meet the need that we have on our waiting list currently,” Fitzgerald said.

Juniper House, Cathedral Square’s latest building in Burlington, is a prime example.

The 70-apartment facility is under construction and isn’t expected to open until February 2021. But it already has more than 300 interested people on its inquiry list. According to Fitzgerald, that list will continue to grow.

The need for affordable housing is real.

“We need more,” Fitzgerald said. “We serve Chittenden, Franklin and Grand Isle County-area and I would say that’s very true in the three of those counties. And I know because of my housing connections throughout the state that affordable housing is needed everywhere.”

But it’s challenging to build affordable housing, Fitzgerald said. Cathedral Square used to open a new facility each year. Now, the organization will be lucky to open a new property every two to three years, she said.

Cathedral Square sought funding from 10 different sources including federal, state and private entities to foot the $19 million construction bill for Juniper House.

Vermont’s affordable housing development is largely enabled through housing tax credits, Fitzgerald said. But with limited resources and great need, those credits are competitive. No more than 25% of that funding, per year, can go towards housing for people aged 55 and older.

That is concerning given the state’s aging population, Fitzgerald said.

“Nobody should have to make a choice between having to pay for medical care or having to pay for food or having to pay for a roof over their head,” she said.

She added it can be one medical expense or layoff that puts a person in a place where they can’t pay their bills.

“There can be this perception of low-income people who are just using the system. That couldn’t be further from the truth from what I see. We have residents who have had professional careers,” Fitzgerald said. “It’s not that they haven’t worked their whole life. They have, they’ve worked hard and they deserve to have housing that supports them.”

Find the gap: Affordability and the minimum-wage earner

Each year the National Low-Income Housing Coalition undergoes an extensive research process to release its “Out of Reach” report. The report determines the gap between what a full-time minimum-wage worker makes and the amount they’d need to earn to afford a “decent” two-bedroom or one-bedroom apartment.

The 2020 report concludes that in 95% of counties in the U.S. a full-time, minimum-wage worker cannot afford a one-bedroom rental at fair market rent.

“In no state, metropolitan area or county can a full-time minimum-wage worker afford a modest two-bedroom rental home,” the report says.

The coalition relied on the assumption that no more than 30% of a person’s gross income should be spent on housing. They also rely on the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Fair Market Rent, which is the amount people would spend for “decent housing” if they were to move today.

“These rents are for minimally decent homes, not for what we might call luxury housing,” said Dan Threet, a research analyst for the coalition.

“In Vermont, the Fair Market Rent for a two-bedroom apartment is $1,215. In order to afford this level of rent and utilities — without paying more than 30% of income on housing — a household must earn $4,050 monthly or $48,597 annually,” according to the report.

That figure translates to an hourly wage of $23.36. In the Burlington-South Burlington metropolitan area that number is about $30.25.

At the state’s $10.96 minimum wage, a full-time minimum-wage earner would have to work 85 hours per week to afford a two-bedroom fair market rent apartment. For a one-bedroom apartment at fair market rent, that person would have to work 68 hours per week.