Editor’s note: Mark Bushnell is a Vermont journalist and historian. He is the author of “Hidden History of Vermont” and “It Happened in Vermont.”

The rumor arose in July 1905: William Clarence Matthews was about to become the first African American player in major league baseball. The news reached Vermont just days after Matthews did. Matthews, who had just graduated from Harvard, had signed to play shortstop for the Burlington team in the Northern League.

The rumor, which first appeared in the pages of the Boston Traveler newspaper, was that Fred Tenney, manager of Boston’s National League club, known by sportswriters simply as the Boston Nationals, was considering adding Matthews to his roster. If a team was looking for a player to test the unwritten rule that kept blacks out of the major leagues, Matthews was an excellent candidate. Matthews had the temperament and intellect to bear the pressure that would come with being the player to break the so-called color line. And, as he had proved while leading Harvard, one of the country’s best amateur teams, he could more than hold his own with the best white players.

Today we know that the rumor never came to fruition. The world would have to wait 42 more years for Jackie Robinson to break the color line. But thank goodness the Traveler printed the rumor. Otherwise, Matthews might have been lost to the ages.

The notice in the Traveler sparked debate in newspapers around the country. That debate was mentioned briefly in a couple of books about blacks in baseball. When Vermont scholar Karl Lindholm saw those few lines, he suspected there was more to the story. He has been working since to resurrect Matthews from obscurity. Lindholm, emeritus dean of advising and assistant professor of American studies at Middlebury College, has written about Matthews for academic journals and other magazines, and is working on a full-length biography. Details in this column come from Lindholm’s research.

A circuitous path led Matthews to Vermont. He was born in 1877 in Selma, Alabama. His parents, assuming he would become a tailor like his father, sent him to the Tuskegee Institute, a technical training school under the leadership of Booker T. Washington. There, Matthews excelled in his studies and at athletics. Someone, perhaps Washington himself, noticed his potential and arranged for him to attend Phillips Andover Academy in Massachusetts to prepare for college.

Matthews learned how to survive and thrive in a white-dominated world. Though he was the only black member in a class of 97 boys, Matthews excelled. He became an editor of the school newspaper, joined a religious debating society and competed in football, track and baseball.

His scholar-athlete credentials gained Matthews admission to Harvard. In addition to running track, he played shortstop for the school’s baseball team. Harvard was one of the best collegiate teams at the time, and Matthews was arguably its best player. Matthews was generally accepted by teammates at Harvard, but his presence on the roster stirred controversy when the team traveled south. Teams from the University of Virginia and the Naval Academy threatened to cancel games with Harvard if Matthews were allowed to play, and he was dropped from the lineup. The next season, Harvard reversed course, supporting Matthews’ right to play and canceling its usual southern tour.

The team did travel as far south as Washington, D.C., however, and conflict erupted again. Its opponent, Georgetown, threatened to cancel the game if Matthews played. When Harvard insisted that he would be in the lineup, Georgetown relented. Matthews played, but Georgetown’s white captain, Sam Apperious, who like Matthews hailed from Selma, refused to take the field. The two would meet again in Vermont.

After finishing his last season at Harvard, Matthews quickly signed with Burlington. It was a sensible choice. The Northern League was considered an “outlaw league,” meaning it wasn’t bound by the national agreement that linked the organized minor leagues. The Northern League didn’t have to abide by minor league rules, like those regarding the movement and salaries of players. More importantly to Matthews, the Northern League could ignore the minor leagues’ informal agreement barring black players. Despite teams’ freedom to sign whoever they wanted, Matthews was the only African American on a Northern League roster. Indeed, Lindholm says, Matthews was probably the only black professional ballplayer playing alongside whites in 1905.

Matthews joined Burlington five games into its 60-game season. His new team, which like the rest of the Northern League had no official nickname, traveled to Plattsburgh, New York, on July 2. Matthews played well that first game and, according to news reports, “was liberally applauded” by Burlington fans who accompanied the team. They had every reason to be excited about their multitalented new player. One newspaper described Matthews as a “brilliant in fielding, a hard thrower, sure at the bat, and a flash of greased lightning on the bases.”

Matthews first played before a home crowd a couple of days later, in a doubleheader against archrival Rutland, whose fans rode trains nearly 70 miles to catch the game. Few cars were seen at games that year, Ford’s affordable Model T being three years in the future. Many local fans traveled to games by trolley, and railroad companies ran extra trains for key games. Matthews had three hits in eight at-bats during the doubleheader and played smoothly in the field. It was an auspicious beginning.

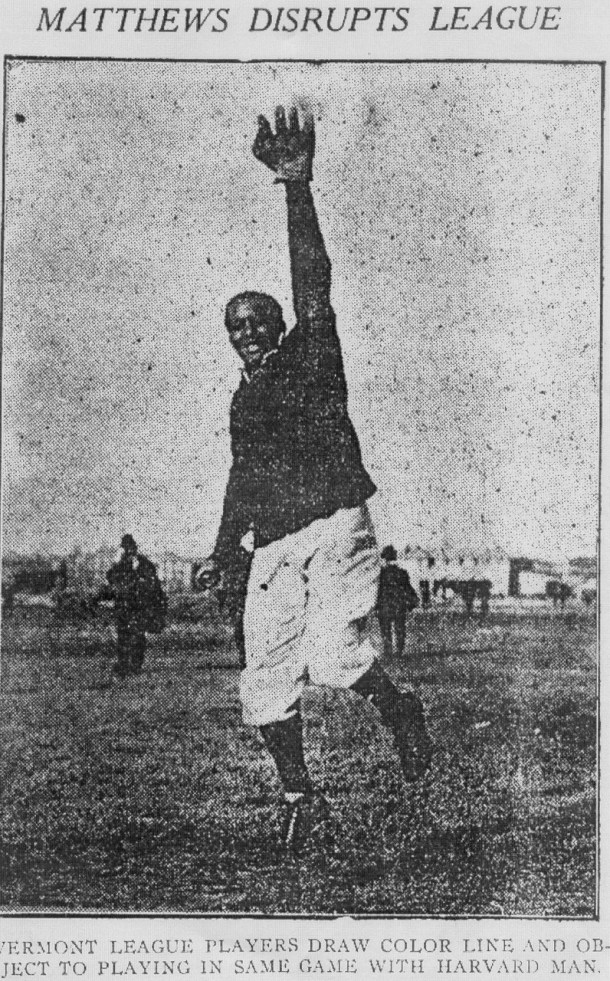

Controversy erupted days later, on July 8, when the Montpelier Argus reported that one of the players for the Montpelier-Barre team (often called “the Hyphens” by sportswriters for the sake of brevity) had declared he would not play against Burlington if Matthews were allowed on the team. The player was Sam Apperious, formerly of Georgetown. Newspaper editorials commented on the affair. Most criticized Apperious. “There is a chap called Apperious in Vermont—came here to play ball,” wrote the Poultney Journal. “Hails from a state where the ‘best citizens’ burn people alive at the stake. … Scat! Vermont has no use for him. Better wash and go South.”

“Matthews received the glad hand from the bleachers and grandstand when he first went to bat,” reported the Burlington Free Press on July 9, “showing that race prejudices did not blind the eyes of the spectators so they could not distinguish a good ballplayer and a gentleman.” But Montpelier-area papers sympathized with Apperious. “(He) would be false to the traditions, sentiments, and interests of southern whites if he should in any way recognize the negro as equal,” wrote the Argus.

Despite the furor, Matthews continued to shine on the field. “(T)he feature of the day,” the Rutland Herald reported on July 13, “was made by Matthews who got first on a hit, stole second and third and then stole home.” Then, on July 15, the Traveler reported the rumor about Boston’s interest in Matthews. Papers around the country picked up the story. Many editorialized about it, dividing mostly along sectional lines. Lindholm wonders whether the rumor might have been concocted to sell papers. The Traveler was one of a handful of newspapers competing for readers in Boston, and the Matthews “scoop” must have boosted sales.

Fred Tenney, the Boston manager, denied the rumor. Matthews didn’t address it directly but was quoted as saying, “I think it is an outrage that colored men are discriminated against in the big leagues. What a shame it is that black men are barred forever from participating in the national game. I should think that Americans should rise up in revolt against such a condition. Many negroes are brilliant players and should not be shut out because their skin is black. As a Harvard man, I shall devote my life to bettering the condition of the black man, and especially to secure his admittance into organized base ball.”

Despite the controversy now swirling around him, and the fact that players regularly left the team for better opportunities, Matthews played in every inning of every game through the end of the 1905 season. When the season ended, and no major league contract materialized, Matthews decided to continue his education.

He moved back to Boston and in 1907 married a Tuskegee schoolmate, Penelope Belle Lloyd. His trip south for the wedding was the last time he would visit the region. To earn money, Matthews coached several area schools and occasionally played as a ringer for town-level baseball teams in the Boston area and in Biddeford, Maine.

But mostly Matthews focused on the law. He attended Boston University Law School and passed the bar in 1908. A recommendation from Booker T. Washington helped Matthews gain appointment as special assistant to the U.S. district attorney in Boston.

Matthews got involved in politics. After World War I, he became a supporter of black nationalist Marcus Garvey and worked for several years as legal counsel for Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association. He also worked for the Republican Party. In 1924, he became director of the Colored Division of the Republican National Committee, whose job was to help get out the black vote. Oddly, he was the first African American to hold the post. Calvin Coolidge ended up winning election with the help of about a million votes from African Americans. Matthews was rewarded with the position of assistant U.S. attorney general.

After the election, Matthews presented Coolidge with a list of 17 proposals to address the underrepresentation of blacks in government. His proposal was reported prominently in the African American press, but largely ignored by the Coolidge administration.

Matthews died just four years later, of a perforated ulcer at the age of 51 in 1928. Though he is largely forgotten today, the public reaction to his death hints at his prominence during his life. The Boston Globe called Matthews “one of the most prominent Negro members of the bar in America.” The New York Age and other African American newspapers reported Matthews’ death in frontpage stories. President Calvin Coolidge, U.S. Attorney General John Sargent and scores of other admirers sent telegrams offering their condolences. Matthews’ funeral was attended by 1,500 mourners. It was all a fitting sendoff for a man who accomplished so much during his foreshortened life.