John Walters is a VTDigger political columnist.

At first, they were admirable.

Now, they’re interminable.

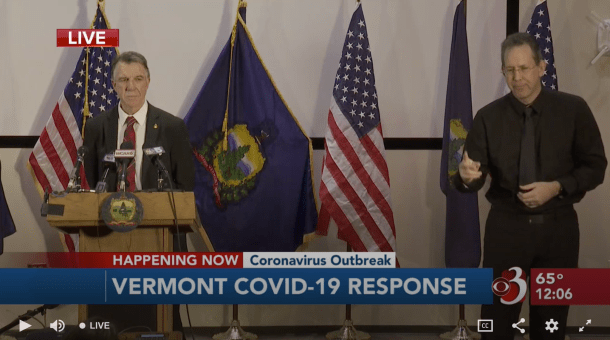

I’m talking about Gov. Phil Scott’s thrice-weekly Covid-19 media briefings, broadcast live on local radio, TV and online. Scott’s goal when he launched this series: To make himself and his administration available to an unprecedented degree, and to make his coronavirus response as transparent as possible. And to do so in a way that complies with social distancing mandates.

Unlike customary gubernatorial press conferences, the briefings can be accessed by telephone. In fact, reporters are encouraged to call instead of risking travel during the pandemic.

That means that any reporter, editor, or freelancer in Vermont can get in line. As a result, the lines are very long, and so are the briefings.

The May 13 briefing clocked in at one hour, 48 minutes. Out of the last 10 briefings, the longest was 1:56; the shortest was 1:29. We’re talking at least four and a half hours a week.

That’s a lot of availability. But is it the best use of everyone’s time?

No.

The briefings cover a huge amount of ground. Scott and several top officials who are up to their necks in Covid-19 response are available throughout these marathons. It’s open season. The questions might range from unemployment to statistics to health care to prisons to food systems to road work, and anything else you can think of.

But there’s no depth. Unlike a “normal” press conference, there’s little opportunity for a back-and-forth exchange — the kind of questioning that forces officials to go beyond their gentle evasions and comfortable talking points.

Why? The format is very restrictive. Reporters have to sign up in advance if they want to ask a question. Scott’s communications director Rebecca Kelley goes down the list, which usually numbers more than 20. Each reporter gets to ask one question and perhaps a single follow-up. There’s no opportunity for an extended colloquy around an unclear statement or important revelation.

At the governor’s May 13 briefing there were several answers that begged for additional inquiry and didn’t get it. Human Services Secretary Mike Smith seemed to announce a major change in the Department of Corrections’ testing policy. Previously, DOC only tested in facilities with a known case of Covid-19. On Wednesday, he said that testing would be conducted at three prisons with no known illnesses — but he only mentioned prison staff, not inmates. No one asked him to explain or clarify.

Michael Harrington, head of the Department of Labor, seemed to indicate that all problems with unemployment insurance had been resolved or would be by the end of the week. This left many lawmakers, who are still fielding numerous complaints from applicants, wondering what he meant.

Twice during his opening statement, Health Commissioner Dr. Mark Levine said that the administration likes “to be as evidence-based as possible with every public health decision.” (Italics mine.) That’s a subtle but profound difference from Scott’s repeated assertion that every decision is based on science and data, full stop. Especially at a time when the governor has ordered retail employees to wear masks, but not their customers. That’s a distinction without any scientific basis.

Scott also gave yet another unsatisfying answer on his continuing, but strangely soft, opposition to a vote by mail system. And no one ever asked about an apparent change made, without notice, to the state’s workplace safety guidance to retail stores. Before, it said that businesses “shall ask Customers, and the public in general, to wear face coverings.” The revised version says businesses “may ask Customers to wear face coverings.” The change brings state guidance into line with Scott’s preference that masks are mandatory for employees but not for customers.

A pre-coronavirus presser would feature the governor and relevant officials standing before a reasonably sized group of reporters. It would often feature robust exchanges between the administration and assembled press, with multiple reporters asking follow-ups to clarify a canned talking point or vague assertion.

Take, for example, March 13, the last time Scott held an actual press conference. That was the day he declared a state of emergency before a room full of reporters and a phalanx of top administration officials. Nobody was practicing social distancing, and not a mask was in sight. (In retrospect, it’s amazing we didn’t trigger an outbreak.)

The format allowed for extended questioning. At one point, Scott and Levine spoke proudly of expanding coronavirus testing to include those exhibiting symptoms verified by a medical professional, instead of testing only those hospitalized with Covid-19. They insisted this was enough, despite the fact that the most successful countries in fighting off the pandemic were those that broadly tested their populations. Reporters were able to fire off a rapid series of questions and gain much-needed clarity on the situation.

The current format also allows Scott to duck inconvenient queries. After the Republican Governors Association launched a video ad on his behalf, Scott was asked about it — and he refused to answer, claiming that the briefing was confined to pandemic questions.

Problem is, he’s not doing any other kind of press availability. There is no forum to ask him about other issues.

There is one big advantage to these sessions. As VPR’s John Dillon reported last week, it gives local media the chance to interact directly with top officials. They can reflect the experiences of everyday Vermonters from all parts of the state. That perspective shouldn’t be lightly tossed away. But we need a better balance between broad questioning and deep probing.

Plus, I wonder about the cost to our busiest officials, Scott included. Does it make sense to have them tied up in press briefings for several hours a week, plus preparation time? They are dealing with an authentic crisis, after all. I shudder to think how many hours Levine and Harrington must be putting in.

I’d suggest a blended approach. Have the governor on hand once or twice a week for major policy announcements, and rotate the other top officials to address specific issues. Economic officials one day, health leaders the next, and so on. That would require a bit more preparation on the part of reporters, but they should be able to handle it.

The total number of weekly briefings might actually increase, but each official’s burden would be lightened. And it would allow deeper discussions of subject areas that get the surface treatment now.

Dillon’s story also quoted Kelley as saying the administration is likely to continue offering a phone-in option to gubernatorial press conferences when (if?) the pandemic passes. To me, the blended approach is preferable. Some pressers should be open to in-person questions only, while others could be more inclusive. Alternate weeks, perhaps.

If the system were completely open, the governor would be more accessible to far-flung reporters. But he’d also be able to evade close questioning, which the Statehouse press corps is best equipped to carry out. Let’s take advantage of a positive outcome of the pandemic without losing the benefits of the old way of doing business.