VTDigger is posting regular updates on the coronavirus in Vermont on this page. You can also subscribe here for regular email updates on the coronavirus. If you have any questions, thoughts or updates on how Vermont is responding to COVID-19, contact us at coronavirus@vtdigger.org

Joe Woodin spends his days — and evenings and weekends — running through worst-case scenarios with one thought in mind: how his rural, 25-bed hospital will cope with a deluge of COVID-19 patients.

For the president and CEO of Copley Hospital in Morrisville, that means a massive interior remodeling effort, a sort of logic puzzle of medical inventories, and a steady stream of phone calls with state and local leaders.

The hospital doesn’t yet have a patient who has tested positive for the virus. But it’s not a question of if it will happen, but when.

The number of cases is rising in Vermont at an exponential rate. As of Sunday, the state had 52 confirmed cases of the virus — more than double the number reported on Thursday. And in the coming weeks, the COVID-19 positive totals are expected to climb sharply, according to the health department. That’s because the coronavirus has already reached the level of “community spread,” and more people who are positive for the disease will be identified through testing.

Dr. Steve Leffler, president and chief operating officer of UVM Medical Center, said the situation is changing rapidly.

The peak of cases could be in late April or early June.

“We are at a point where we will see more COVID patients each day,” Leffler said. “We are living in an epidemiological experiment.”

In the past week, UVM Medical Center has seen an increase in patients testing positive for COVID-19, and more are presenting with serious symptoms, he said.

Woodin, and hospital leaders across Vermont, are scrambling to prepare for a previously unmatched influx of patients in acute distress. In Bergamo, Italy, Wuhan, China, and now, New York City, health care systems have been overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients. Life-saving ventilators have had to be rationed; thousands of people died. Patients were housed in makeshift facilities, including tents and warehouses.

Vermont hospitals are grappling with many unknowns: the number of people who could be infected, the demand for intensive care and ventilators, how many providers could be needed, and whether supplies will hold out.

“We are constantly running the films forward thinking about ‘OK when this happens, what are we going to do? When this happens, what are we going to do?’” Woodin said. “It doesn’t end, every day we kind of do a little bit better — better, faster, quicker.”

Among his strategies: Woodin and his staff have rerouted ambulances to an alternative entrance to provide COVID-19 patients a separate space. They’ve added a curbside, drive-up test site for testing six days a week. In a pinch, staff could use stretchers as beds, Woodin said.

Like Copley, hospitals in Vermont have prepared for potential tsunami of cases. They have overhauled staffing plans, canceled non-essential surgeries, and banned visitors in most cases.

“You can be rest assured, if there’s a scenario we are planning for, it is the worst case scenario,” Health Commissioner Mark Levine said.

It is unlikely to be enough.

Conservative estimates from epidemiologists indicate that about 30% of Vermonters, or 188,000 people, could get the virus. If global statistics hold steady, about 5% or 9,800 Vermonters could be hospitalized over a period of months.

Of those, 3,800 Vermonters could require an intensive care unit, and 1,900 may need ventilators, according to James Lawler, an infectious diseases specialist and public health expert at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

With little support from the federal government and a shortening timeline, worst case-planning and dawn-to-dusk preparation is the best hospitals can do, said Jeff Tieman, president and CEO of the Vermont Association of Hospitals and Health Systems. “This is rapid response,” Tieman said. “It’s literally not possible to be ready for something at the level we’re facing right now.”

A shortage of space

The University of Vermont Medical Center’s new testing facility is located at the Champlain Valley Expo in Essex Junction. The pop-up test site, staffed by the medical center’s critical care transport team, was launched last week.

On Wednesday, cars pulled up to a pop-up tent. A paramedic in a gown and mask took samples from drivers by inserting a swab about three inches into each person’s nose. The swabs — all 72 collected that day — were submitted to the Department of Health for analysis.

The pop-up site, and others like it, are part of an effort to conserve resources and divert an influx of highly infectious patients from streaming into hospital emergency departments.

Hospitals around the state are reshuffling beds to accommodate a deluge of patients that could outstrip the current capacity. Vermont already has fewer hospital beds per capita than most other states.

Josh White, the chief medical officer at Gifford Medical Center in Randolph, compared the influx to pouring three gallons of liquid into a gallon milk jug. The volume of patients will be “potentially a lot larger than we normally handle,” he said. “It’ll be occurring in every hospital in the region. Offloading [patients to other hospitals] is going to be a very limited option.”

Gifford, which has no intensive care unit beds, is outfitting a “step-down unit” as an ICU, White said.

The University of Vermont Medical Center set aside four units and put up a wall to separate rooms for coronavirus patients, said spokesperson Annie Mackin. The hospital has 40 intensive care units, but ultimately, the entire new Miller wing of the hospital, with 128 beds, could be converted to critical care rooms for COVID-19 patients, according to Leffler, of UVM Medical Center. In theory, all 499 rooms at the hospital could be used for coronavirus patients, he said.

The White River Junction VA Medical Center is adding seven intensive care unit beds, doubling its current number, according to Seven Days. Two vets there have already tested positive for the coronavirus, one of whom has died.

Copley’s status as a critical access hospital means their capacity is technically limited by the federal government to 25 beds, Woodin said — though “there is a lot of forgiveness” in emergencies.

The state has temporary “surge” sites planned if needed, according to Michael Schirling, the commissioner of the Vermont Department of Public Safety.

Officials are planning for eight sites — auditoriums, hotels, field houses, colleges — based on medical needs, with space for 50 patients each. Two will be put in place early this week, according to Schirling.

The Vermont National Guard will assist with setting up the temporary facilities, which will be geographically distributed and located near hospitals. One of the field hospitals will be located outside the UVM Medical Center emergency department for coronavirus screening, Leffler said. If need be, Col. Randall Gates suggested that the University of Vermont’s Gutterson Field House could be used as a morgue.

A shortage of supplies

Administrators are keeping close track of supplies, reporting their stock to the state every day.

“We are monitoring basically every medical supply we have in the hospital,” said Matt Choate, chief nursing officer for Central Vermont Medical Center.

The doctors and administrators who spoke to VTDigger all worried that they’d run out of personal protective equipment — masks, gloves, and gowns — and none could say how long supplies would last. It “depends on if, and when, we get any kind of resupply,” said White of Gifford.

Shortages — and resulting conflict — have already been reported across the country. In Washington state, health care workers started making masks out of office supplies. In New York, a fight broke out among workers for masks.

- Related stories: Vermonters seek COVID tests — and can’t get them.

- Vermont could have 16 times more infections than reported.

In anticipation of similar scenarios, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center has already asked people to clear out their cabinets and donate hand sanitizer, face masks and gloves to doctors. Sewing groups and two companies have stepped up to help supply materials and make masks from cloth.

Ted Brady, deputy secretary for the Agency of Commerce and Community Development, put out a call last week asking companies that have face masks to donate any “that aren’t essential to their business” to Vermont hospitals.

“These masks have become increasingly difficult to procure, and are emergently needed in our healthcare facilities,” Brady said in a statement.

The state has spent $3 million on 112 ventilators, which will bring the total in Vermont to 265. A University of Nebraska-Lincoln researcher estimated that half of ICU patients in Vermont will need ventilators — upwards of 2,500 in the Burlington region — over the course of the pandemic, which epidemiologists say could last six to 18 months.

“If the pandemic hits the Northeast Kingdom, we obviously wouldn’t have enough ventilators,” said Franklin, of North Country Hospital in Newport. More are also on the way for Gifford Medical Center, which has three, according to White. But, he added, “I’m not going to declare victory until they arrive.”

The UVM Health Network, which includes the UVM Medical Center, Porter Medical Center, and Central Vermont Medical Center, has about 100 ventilators, Leffler said.

Dartmouth-Hitchcock officials would not say how many ventilators are in stock.

White said the coronavirus will have a ripple effect on patients far into the future. Gifford and other hospitals must balance caring for patients who need routine medical care designed to prevent more expensive, urgent procedures that may be needed if care is delayed, he said.

Then there’s the impact on the bottom line. Small hospitals are already struggling financially, he said. “We’re trying to keep our heads above water and this is not going to help.”

UVM Medical Center will also take a hit. The facility started operating at 50% capacity last week after all non-essential visits, surgeries and procedures were canceled, Leffler said. The cancellations conserve personal protective equipment, allow doctors to rest in anticipation of a COVID-19 surge, but delays in surgeries and other procedures also cost the hospital money.

A shortage of staff

On Friday, the state’s first health care worker tested positive for the coronavirus. Central Vermont Medical Center, where the clinician worked, started screening staff members the next day.

The case highlighted a looming concern among hospital leaders: a growing number of self-quarantined staff could limit the system’s ability to care for those who need it.

Administrators agreed that a shortage of health care providers — not space or materials — will be the limiting factor in how many patients hospitals can accommodate. Scarcity of staff is “the fear across the board,” said Wendy Franklin, spokesperson for North Country Hospital in Newport.

Vermont hospitals are already short-staffed. A rural health care taskforce report from January found that the state has 3,900 nursing job vacancies. The state doesn’t have enough volunteer emergency services personnel or Medical Reserve Corps volunteers, according to a Vermont Department of Health scorecard.

“Our workforce is strained on a normal day,” Tieman said.

Administrators said it was impossible to know how many additional workers they’d need or how much a shortage would impact care.

The state is trying to eliminate roadblocks for hiring. Secretary of State Jim Condos announced Wednesday that the Office of Professional Regulation will issue temporary licenses to health care workers without a Vermont license. Under orders from Gov. Phil Scott, the state can waive licensing fees for health care workers. As state-designated “emergency workers,” hospital staff are eligible to receive child care.

Hospitals are looking at creative ways of scheduling workers and shuffling staff.

UVM Medical Center has a “four deep model,” Leffler said. The hospital has mobilized teams of emergency department physicians, critical care doctors and pulmonologists ensuring that each doctor has sufficient backup.

At Gifford, a sports medicine doctor with emergency room experience is applying to move back to the emergency room, and nurses who work with him will move to the emergency room as well, White said.

White is trying to plan for the long term. The goal? “Bring in extra help rather than working people till they drop.”

Workers, preparing for the virus, have been inundated by new information, said Deb Snell, a nurse at the University of Vermont Medical Center and president of the nurses union. Housekeepers must learn to disinfect rooms, Snell said. Nurses are being shuffled to different departments.

It’s “information overload,” she said.

One health care worker, who spoke with VTDigger on condition of anonymity, compared the work environment to “trying to hold Jell-O.”

“Every day there is a new piece of information, or a new challenge, that upends decisions from the previous day,” the worker said.

Tieman, of the hospital association, said the impacts of COVID-19 have already taken a toll on hospital staff. “There’s not a single person in a single hospital who’s not totally engaged and working around the clock,” he said.

Another clinician, who’s employed at Dartmouth-Hitchcock and who also asked not to be identified, said the hospital has been redeploying resources and changing the workflow broadly among staff.

The hospital has a “calm before the storm” feeling, the staffer said.

On a normal day, Dartmouth-Hitchcock has so many people on its campus that it would count as the fifth largest city in New Hampshire. But because of the cancellation of all non-essential office visits, procedures and surgeries, it is like a ghost town, with empty cafeterias and few people in the hallways. Only medical staff and the most acute patients are allowed in the 396-bed facility.

In advance of the storm, the hospital has cross-trained staff and has given COVID-19 nurses and doctors two hours of specialized personal protective equipment training. It takes two people to put on and take off PPE clothing, which includes a dressing gown, apron, gloves, a hat, respirator and face mask and other equipment.

Dartmouth-Hitchcock is used to working at capacity during cold and flu seasons, and once a year has a surge training for a mass casualty situation like a bus accident.

In this case, a separate area of the hospital will be used for COVID-19 patients. Anyone who comes to the emergency department with symptoms will be put in an isolation area.

The hospital has limited transfers from other hospitals, in order to accommodate a surge of patients with the virus. Dartmouth-Hitchcock is urging doctors at other hospitals to keep patients local and will offer COVID-19 telemedicine monitoring to help facilitate care.

UVM Medical Center also holds disaster preparedness drills once a year, simulating airplane crashes, shootings and sometimes pandemics. The hospital practices standing up a incident command center.

“The things we’re putting into place now are just in a real situation,” Leffler said.

A shortage of time

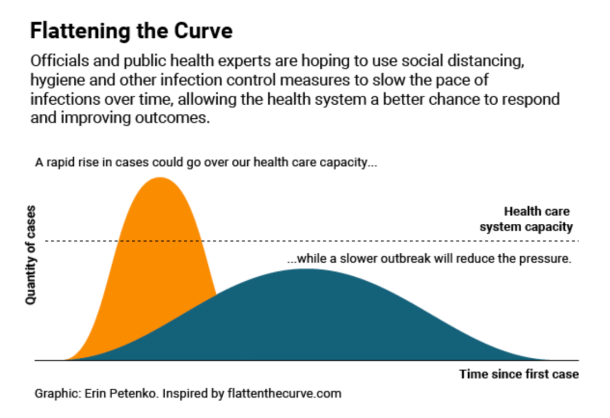

With limited capacity and shifting information, hospitals are banking on a less technical approach to preparation: slowing the spread of infection and keeping patients out of the hospitals in the first place.

White said he was pressuring Randolph-area nursing homes and the local mental health agencies to keep people isolated and at home. Keeping those vulnerable populations out of the hospital was the best way to stretch hospital resources farther, he said.

His message? Social distancing “is everyone’s responsibility.”

“You might be 29 years old and healthy. It is, in fact, your job to care about the vulnerable people around you,” he said. “And if you don’t care, you blow this off and you go to a bar or you go out to a neighborhood party because it’s awesome, that can be the death of somebody in our nursing home. That’s not an exaggeration.”

People will get sick, but hospitals will be able to handle the patients if they come in over the course of six months or a year rather than within the next few weeks, said Choate, from Central Vermont Medical Center. Isolation “will hopefully bend that pandemic curve in our favor, he said.

According to Tieman, that will likely be the best case scenario for an already-strained system. For now, health care workers are urging people to stay home and taking challenges as they come. “As a hospital community, we’re focusing on the things we can do most immediately and most effectively to mitigate the situation,” he said.