Editor’s note: Mark Bushnell is a Vermont journalist and historian. He is the author of “Hidden History of Vermont” and “It Happened in Vermont.”

Charles Dalton must have felt helpless. He saw disaster coming, but could do nothing to stop it.

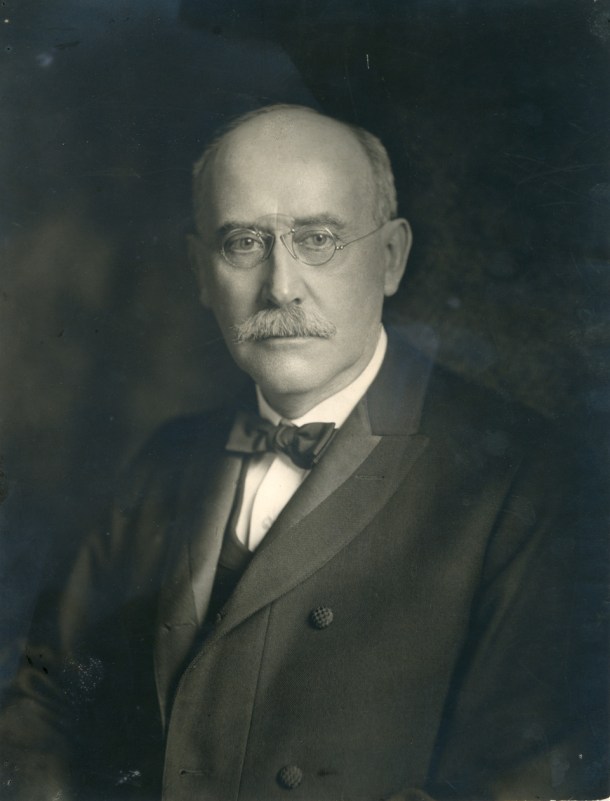

The dreaded Spanish influenza that had ravaged Europe starting in the spring of 1918 was about to strike Vermont. As secretary of the Vermont State Board of Health, Dalton could do little more than chart its progress as the disease tore through the state. On Sept. 21, he ordered local health officers to report any influenza cases. Three days later, the state’s newspapers carried his warning that the epidemic would reach Vermont in the coming days or weeks.

Dalton’s prediction proved optimistic. The disease was already here. Forty students at Middlebury College and 60 at Norwich University were sick, the Rutland Herald reported that day. They were among the first of perhaps 50,000 of Vermonters who would be stricken. More than 2,100 would die.

The world was facing one of its worst epidemics ever. In little over a year, the disease would kill an estimated 20 million to 50 million people worldwide, nearly half of them in India. In comparison, the Black Death, which ebbed and flowed in medieval Europe, killed far more; estimates range anywhere from 75 million to 200 million, but its victims succumbed over the course of three centuries. In the United States, the Spanish influenza would kill 675,000 people, more Americans than died in all the wars of the 20th century combined.

Calling the virus the “Spanish influenza” is a misnomer. Researchers now believe the disease started at Fort Riley, Kansas, with an outbreak among soldiers in March 1918. Those soldiers carried the disease to Europe when they shipped out to fight in World War I. The virus spread quickly among the troops, who were clustered together in unsanitary conditions. Germany, England and France censored reports of the disease, for fear of hurting their war effort. Spain, as a neutral country, did not. So Spanish papers were the first to report the outbreak, and the disease became linked with Spain.

The name “influenza” is also something of a misnomer. During an outbreak in Italy in the 16th century, many people believed the disease was caused by the influence of the stars, hence the Italian word “influenza” became attached to the ailment.

The 1918 influenza pandemic still haunts epidemiologists. It killed so many by being highly contagious. In the days before global air travel, the disease managed to span the world. And it did so in a time before antibiotics. Though antibiotics don’t treat viruses like influenza, they could have treated the secondary bacterial infections, such as pneumonia, that were leading causes of death during the pandemic.

Charles Dalton understood that these secondary infections were the real danger. “The disease itself is not serious; the complications frequently are,” he wrote. “Hence, the disease should not be slighted.”

Fear of the flu pandemic went beyond the sheer number of victims. People were also frightened by who this mysterious pandemic was killing, and how. Nearly half of those dying were in their 20s and 30s. Scientists are still puzzled by the 1918 flu’s ability to kill people in their prime. One theory is that these victims’ strong immune systems worked against them by going into overdrive trying to fend off the unknown virus, and ended up filling their lungs with fluid. Many victims essentially drowned in their beds.

In 1918, Gifford Owen was 10 years old and living in Montgomery Center when he got the flu. Owen remembered almost nothing from the first few days he was sick. “I was out, just completely out,” he told an interviewer in 1998. Owen’s sister Viola was the only one of the eight family members who didn’t become ill even though she spent days caring for others.

While Owen lay sick, the epidemic tore through town. People did what they could to help one another. Chicken soup was the cure-all of the day. “Whether you had whooping cough or a sore foot, it didn’t matter,” Owens said, “that’s what you got.” So Emma Shover, a deaconess at the Baptist church, made a kettle of chicken soup and used a wheelbarrow to deliver it to the houses of the sick. Elsewhere in town, Colonel Slater, vice president of Nelson & Hall Tub Mill, took an axe to the sugar and butter tubs and Victrola cabinets his company made and delivered firewood to shut-ins. In the following weeks, Owen’s grandfather Eli Manosh and his great-uncle Edmond Manosh would put wood to another use. They would build 200 coffins for people who died in the area, Owen said.

Gov. Horace Graham, at home in Craftsbury, was disturbed by the newspaper reports he was reading. He wrote Dalton on Sept. 26: “Do you not think some general action ought to be taken by the Board with reference to this epidemic. If it is contagious what about permitting all these conventions and meetings(?)”

Graham also worried what effect banning gatherings would have on the sale of Liberty Bonds to fund the war in Europe.

The next day, Dalton issued an order to local health officials. While the state probably would not close schools, churches and other places of public assembly, he wrote, health officers should know they have the right to do so.

“Health officers,” he continued, “should make it plain to all persons that the disease is spread by coughing and sneezing in public or around other people.”

Funerals for flu victims were allowed, Dalton said, but anyone who had been in contact with the sick was barred from attending.

The flu killed quickly. By the end of September, Vermonters were dying in waves. In the hardest hit community, Barre, 10 people died over the weekend of the 28th and 29th. Twelve more died on the 30th and the morning of Oct. 1. The next day, 17 more would die.

“Undertakers, between ambulance calls and more serious missions, are having little time for sleep,” reported the Barre Daily Times at a time when funeral homes often ran the local ambulance service.

Front-page obituaries, briefly outlining the life and death of a baker, a policeman, a housewife, a stonecutter, began crowding out news from the battlefields of Europe. The papers’ social notes, usually filled with talk about who was visiting whom, now reported who was ill.

Some people saw the epidemic as a business opportunity. One newspaper advertisement for Vick’s VapoRub and other products offered advice on how to beat the flu. Below it was an ad for the Perry and Noonan Funeral Home, which promised “unexcelled funeral furnishings.” An ad for Moore and Owens, Clothiers in Barre, suggested that “a raincoat is almost an absolute necessity at any time, but especially during this epidemic, when the slightest over-exposure to dampness may find a victim.” Another company suggested a different approach, pitching “blood-building tonic” to the healthy. “To ease the stress on family members of the ill,” the ad read, “take Dr. Williams’ Pink Pills.”

Communities and institutions began taking what precautions they could to halt the disease’s progress. St. Johnsbury banned public meetings. With half the students out sick in some grades, Barre closed its schools, as did Montpelier and Wells River. The state Supreme Court postponed the start of its session. Many companies experienced a 50% sick rate and struggled to stay open. Some rural telephone exchanges shut down as switchboard operators fell ill.

The Brattleboro Reformer urged people to take sensible precautions. It told any worker with flu-like symptoms to go home and call a doctor. “(D)on’t imperil your own welfare or that of your fellow employees by trying to ‘stick it out.’ ” the paper wrote “…(It is better) that you are temporarily off duty than that you risk your life through a mistaken idea of loyalty.”

Some Vermont communities pleaded for more doctors. The University of Vermont sent medical students on a special train to Barre. Rutland’s call for more nurses went largely unanswered. Medical personnel went where the need was greatest.

Vermont was not alone in the crisis. In late September, Massachusetts’ Lt. Gov. Calvin Coolidge wired surrounding states, asking for doctors to treat the ailing in his state. Gov. Graham responded that Vermont could spare none. Nationwide, one-quarter of all the nation’s doctors and one-third of its nurses were serving in the military. During the war, Vermont had only one doctor for every 745 residents.

On Oct. 4, Dalton took the step he thought would be unnecessary: He ordered all of Vermont’s schools, churches and theaters closed, and prohibited all public gatherings. The Rutland Herald tried to console its readers, who it feared would become bored at home. “The ‘quiet evening at home,’ with children playing sensible table or floor games, the young folks reading or musicking and the old folks writing or supervising the play, is no bad substitute for theater. It ought to grow in popularity with use.” Evidently, not everyone was convinced. A Rutland pool room was caught violating the ban. Rutland Mayor Henry Brislin promised to punish anyone who disobeyed Dalton’s order. The Burlington News saw local reaction to the ban as an opportunity to scold the irreligious. “We fear there are some Burlingtonians who regret more deeply the closing of the ‘movie’ theaters than they do the closing of the churches,” the paper wrote.

Numbers bore out the need for the ban. By the end of the first week of October, Barre was reporting 2,000 flu cases. Montpelier had 500, St. Johnsbury 842 and St. Albans 750. In contrast, Rutland City had 146 cases, Proctor 169, Brattleboro 86 and Manchester 10. Springfield and Hartford were the only hard hit towns in the state’s southern half, with 692 and 584 cases respectively. Among Brattleboro’s flu sufferers was a family of seven that was rushed to the hospital. Middlebury College banned students from leaving campus and turned the second floor of Hepburn Hall into an influenza ward.

On Oct 7, Dalton estimated that 10,000 Vermonters had the flu. A week later, he would raise his estimate to 15,000. Many Vermont communities became ghost towns. Barre’s quarries closed because they couldn’t find enough healthy workers. The National Life Insurance Company in Montpelier was missing about half its employees. Brattleboro had to close its public transportation system because the last two functioning street cars had broken down and there were no healthy mechanics to fix them.

Blanche Adams’ parents wanted to take no chances. They decided to pick up their 14-year-old daughter from school at Sacred Heart Convent in Newport and return home to Beebe, Quebec, just across the border. Her stepfather believed the way to survive this epidemic was to inoculate the family against the flu with brandy. At the time, doctors saw alcohol as a partial cure. (In fact, during the epidemic Burlington Mayor J. Holmes Jackson ordered alcohol to be distributed free from City Hall to anyone with a doctor’s prescription.)

But Blanche was having none of it. She had just been confirmed in the church and she was sure that drinking would violate her vows. “I put up a royal fuss,” she told an interviewer decades later. Her parents called the town priest and handed the phone to Blanche. Only when he told her the brandy counted as medicine would she agree to a daily dose. It probably wasn’t the alcohol, but Blanche and her parents survived the epidemic untouched.

In Topsham, pediatric nurse Annie Batchelder used old pillow cases to hold hot mustard plasters, which she placed on the chests of her daughters and husband to break the phlegm. She lay heated bricks in their beds to ward off the chills. All the while, Annie ran the family farm, milking the cows, tending the chickens.

The flu was claiming more victims than the war. Between Sept. 1 and Oct. 7, the Barre Daily Times noted, 15 Vermont soldiers were killed in action, but 37 died of pneumonia after contracting the flu.

The epidemic devastated families. A father and son in the Pombrio family of Barre died on Oct. 4. The mother died on the 6th and her 17-year-old son followed her to the grave four days later, leaving three brothers and sisters to fend for themselves.

Barre would lose 177 residents to the epidemic. The death toll was particularly high in Barre, researchers believe, because so many local men worked in the granite industry, where they inhaled rock dust that weakened their lungs.

Death rolled by Madeleine Bryant’s home every day. The house, located in Websterville, was on the road to four local cemeteries, so Bryant had a good view of the horse-drawn hearses passing. “Every day there were three or four or five going by,” remembered Bryant, who was 11 at the time. “We’d say, ‘There goes another one. Isn’t that awful?’” One day a particular hearse caught her eye. A girl about her age had died. She was being carried to the cemetery in a white hearse. Through the wagon’s window Bryant could see the girl’s white casket. She recalled being impressed by how fancy it was. Alene Livendale, who was 10 at the time, remembered the hearses, too. But it wasn’t the sight of them; it was the sound. As an adult, Livendale would tell her daughter how she would lie awake at night in the family’s North Main Street home in Barre and hear the clack of hearses’ wooden wheels against the cobblestones.

By mid-October, the epidemic seemed to have peaked. On Oct. 14, readers of the Rutland Herald were relieved to see headlines promising better times. “Brattleboro on the mend,” one announced; another read: “Montpelier continues to improve.” By Oct. 15, the Barre Daily Times could declare: “Barre no longer lies supine in the grasp of influenza and pneumonia, as decreasing death lists and rapidly increasing recovery totals plainly indicate.”

The worst was over. On Oct. 31, Dalton announced he was lifting his ban on public gatherings. With his new order, Dalton also lifted the pall that had shrouded daily life. Less than two weeks later, world leaders signed the armistice ending the world war. Peace quickly overshadowed the pandemic that had devastated the world.

But scars from that period remained with Vermonters. Most probably knew someone who had died. The epidemic killed about one out of every 170 Vermonters.

Decades later, Gifford Owen recalled the day his parents allowed him to leave his sickbed and walk several blocks on an errand. Recent rains had turned the roads muddy, but the day’s cold weather had formed a crust over them.

“Horses’ hooves left hundreds and hundreds of mirror-like holes in the road,” he said. “Breaking those little ponds was such a delight.

“Even the air was different. I remember breathing real hard to inhale something I hadn’t felt in weeks. … And the wonderment of being able to walk, it was as if you had come back from the grave.”