Editor’s note: Mark Bushnell is a Vermont journalist and historian. He is the author of “Hidden History of Vermont” and “It Happened in Vermont.”

During financial collapses, you only know in hindsight when you hit bottom. During the Great Depression, economists can now say that 1933 was about as bad as it was going to get.

Perhaps that explains why President Herbert Hoover had not acted more aggressively at the start of the Depression. His response had been to keep a tight rein on spending. In retrospect, that decision only helped to add Hoover to the nation’s unemployment rolls. Hoover’s approach hadn’t work, so Americans turned to Franklin Roosevelt to chart a new course, which involved throwing the federal government’s financial weight behind a massive jobs-creation plan that he dubbed the New Deal.

Vermonters weren’t sure what to make of this sudden federal largesse. They had always felt uneasy about federal power being exercised within the state’s boundaries. That preference for keeping the federal government small helped make Vermont a reliably Republican state for generations. In fact, Vermont was one of only six states that Hoover, the Republican candidate, won in the election of 1932.

Roosevelt’s landslide gave the new president the mandate he needed to push his New Deal, which was just the sort of thing most Vermonters usually disdained. But these were desperate times. Ideology be damned: Vermonters were willing to try anything that might work.

People like to say that Vermonters were so poor before the Great Depression that they never noticed its arrival. The numbers tell another story. In 1928, the year before the stock market crash, Vermont industries produced $143 million worth of goods. By 1933, that figure had dropped to $57 million. During the same period, the number of industrial workers in Vermont fell from 27,000 to 15,000. The agricultural sector was similarly impacted. By 1933, farm workers’ relative wages had dropped to their lowest level since 1877.

Vermonters had long prided themselves on their self-sufficiency. But that attitude was changing in the aftermath of the devastating Flood of 1927. Despite the enduring myth that the state rebuilt itself without outside assistance, the massive reconstruction of Vermont had been accomplished with the help of substantial federal aid.

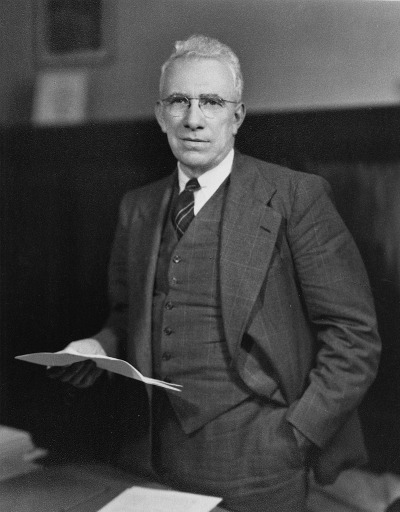

When the Depression hit, one Vermonter who saw the benefit of federal help was Perry Merrill, the state forester. On March 21, 1933, two weeks after his inauguration, Roosevelt issued an executive order creating the Civil Conservation Corps, a program that would ultimately employ 3 million impoverished young men on public works projects. Merrill pounced on the opportunity. Within a week, he submitted proposals for several CCC camps in Vermont. Soon Vermonters and out-of-state workers were starting infrastructure projects around the state.

Vermonters could accept this federal program apparently because the CCC rewarded young men for hard work, and 80% of the men’s pay was sent directly to their struggling families. And perhaps more importantly, CCC workers were doing work Vermonters valued, like building dams to prevent future floods.

During the course of the next decade, the CCC would operate 30 camps in Vermont, employing 41,000 men, more than 11,000 of them Vermonters. The CCC helped cut the state’s unemployment numbers, which one historian estimated totaled 50,000 people in 1933. (Since towns, not the state, arranged aid for the poor, no exact unemployment figure is available.) The federal government also provided Vermont with more than $3 million for unemployment relief.

The desperation wrought by the Great Depression had forced Vermonters to change their mindset about federal aid. But some federal proposals still rankled Vermonters, because the ideas were seen as threatening Vermont’s sovereignty.

One such proposal was the Green Mountain Parkway. The project called for construction of a 260-mile-long road along the heights of the Green Mountains, along Glastonbury Mountain, Killington Peak, Camel’s Hump and Mount Mansfield to the Canadian border. The highway, proponents said, would attract tourists.

Vermont’s share of the $18 million project would be a mere $500,000. That money would buy rights-of-way along the route, which the state would transfer to the federal government as part of a national park. The parkway had the support of prominent Vermonters, including writer Dorothy Canfield Fisher and Green Mountain Club founder James P. Taylor, though the club itself fought it.

Opponents argued that the road would scar the state’s beloved Green Mountains, invite development into the wilderness, draw tourists and their money away from villages, and attract a “flood of undesirable visitors.” It didn’t help that the federal government would control a ribbon of land the length of the state.

Vermonters rejected the parkway in a statewide, nonbinding resolution on Town Meeting Day in 1936. After that, no politician would touch it.

During the parkway debate, the federal government pursued another major land project. No referendum was called to defeat this one. Vermont leaders killed it themselves.

The Rural Rehabilitation Program was not dead on arrival, however. Vermont leaders expressed early interest in the program, which would have resettled 13,000 Vermonters from farmland the federal government deemed “submarginal” to more productive land.

The farms, mostly upland farms located in southern and central Vermont, had soils too poor to afford inhabitants a decent living, the federal government argued. A state study done in 1929 had reached similar conclusions.

The program called for the land to be sold to the federal government, which would convert it to timber forests or recreation area. The land would then be leased back to the state, with the federal government retaining mineral rights. Gov. Stanley Wilson was ready to sign on, appointing a committee to select which acres would be “retired.” Federal officials moved ahead with their plans.

Then, in 1935, the newly elected lieutenant governor, George Aiken, attacked the plan. Aiken, a nursery owner from Putney, thought federal control of the acreage threatened the state’s wellbeing more than the continued farming of so-called “submarginal” lands.

Aiken said that if federal officials were worried about poor Vermonters, they could have done more good by spending half the money proposed for resettlement instead on new roads, schools, libraries, and power lines for the affected communities. “It would have enabled the people who already live up in the hills to secure a greater share of the luxuries of life to which they are entitled,” Aiken later wrote, “but for which they will never surrender freedom.”

With Aiken leading the opposition, the plan died. Vermonters were willing to accept federal aid, but only on their own terms.