The Deeper Dig is a weekly podcast from the VTDigger newsroom. Listen below, and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Spotify or anywhere you listen to podcasts.

While the Catholic Church has faced allegations of child sex abuse in court and in public for decades, a new report by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Burlington details for the first time the problem’s scope in Vermont.

The report, prepared by a lay committee over the past ten months, names 40 priests who have been credibly accused of abuse over the past seven decades — and describes the role of church officials in covering up those accusations.

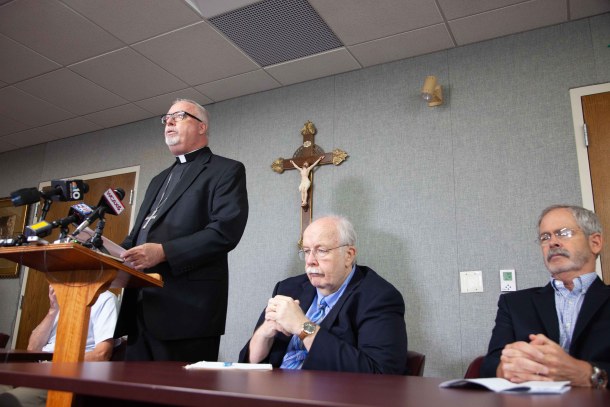

“While most of these allegations took place at least a generation ago, the numbers are still staggering,” Bishop Christopher Coyne said at a press conference Thursday announcing the committee’s findings.

Coyne said he expects the report could lead more survivors of abuse to come forward.

But a state law enacted this year will have a direct impact on the legal options available to accusers. Vermont lawmakers last session repealed the statute of limitations for civil actions based on childhood sexual abuse.

Bishop Coyne said that the move “just blows my mind, in terms of justice.” Coyne said the church will eventually run out of funding to settle civil suits related to the sex abuse scandal. In that case, the diocese may have to go to court, and likely appeal, arguing against the statute of limitations repeal.

“It doesn’t allow us to make a just defense,” he said.

But Coyne said that despite the potential legal consequences, the purpose of compiling the report was to reach victims that were still alive. “If someone was abused,” he said, “I want to give them the justice that they’re due.”

On this week’s podcast, Bishop Coyne discusses what the report means for the diocese and for survivors. Plus, VTDigger’s Kevin O’Connor describes how public perception of the church abuse scandal has evolved over his nearly 20 years of reporting on it.

[Podcast transcript]

This week, the Catholic Church in Vermont has released the names of 40 priests credibly accused of child sexual abuse since 1950 — and acknowledged the church’s role in covering up those accusations. But what does that mean for survivors of abuse and for the church in 2019?

Last fall, when the church announced that it was doing this research, we talked to Bishop Christopher Coyne about his approach to survivors of abuse. Here’s what he said:

Coyne: When they come in, and I talk to them, I say, just tell me what you think I need to hear. And they’ll tell me their story. And oftentimes, they’ll make reference to what happened to them, but they don’t get into details. They’ll just tell me, this is what happened. This is what happened in general. Then they’ll talk about really kind of the fallout in their life.

I think more than anything else, they just want to tell their story, because for the longest time, they didn’t think they’d be believed. Or they did tell their story and they weren’t believed. And so just to have one more person with a collar in a position of authority, who hears the stories and says ‘I believe you,’ is a very healing moment for them.

On Thursday, Bishop Coyne appeared at a press conference to discuss the new report,

Coyne: Good morning everyone.

The Diocese of Burlington this morning published a report listing the names of diocesan clergy, who since 1950, have had a credible and substantiated allegation of sexual abuse of a minor made against them.

Kevin O’Connor: I traveled to the offices of the statewide Roman Catholic Diocese of Burlington on Thursday for what was really an unprecedented press conference.

Kevin O’Connor has been covering the church abuse scandal for VTDigger.

O’Connor: It was the first time that the church was opening up its personnel files and acknowledging that there were 40 priests that it knew of who had credible allegations of child sexual abuse. And that the church was also acknowledging not only did they have the files, but they never acknowledged that to the public, or to the police, in the more than seven decades that they’ve been keeping them.

Coyne: These sins of the past continue to haunt us. These shameful, sinful, criminal acts have been our family secret for generations. While there has been a significant action by the church here in Vermont, and in the United States to address the issue of the sexual abuse of minors by clergy and the cover-up of those crimes by those in authority, the whole sordid tale of what happened in the decades leading up to the U.S. bishop’s charter in 2002, has not been fully aired. That is why I asked for this report to be compiled, and published.

Accusations like this have been around for a long time now. And similar allegations have been made public to varying degrees at varying times. What was new about this? What happened over the last several months that led us to this point?

O’Connor: I think what was interesting was, I’ve covered the church and the child sex abuse scandal since 2002. And for me, this was a summary of, in effect, everything that has come out for the past 20 years. But I’m unique in terms of being a reporter who’s paid to sort of follow the drip, drip, drip over time. I think for a lot of the public, it’s the first time they really understood the extent of the problem.

Coyne: While most of these allegations took place at least a generation ago, the numbers are still staggering. Forty priests, who served in the Diocese of Burlington since 1950, abused children.

O’Connor: In terms of the 40 names that were released, about half of them had already had their names come up in court in several lawsuits by some of those who had been abused, and were taking the diocese to court. The other half were new names in terms of had credible allegations against them. I think overall, though, the fact that they were all being put forward by the organization that’s kept them secret for six, seven decades, was the news.

Coyne: There are people who have left the church because of this, who will never come back. Whenever anybody, oftentimes when people leave a church or an organization for a reason, you can’t get them back. And the violation of trust at the deepest level, when you are talking about children being abused, that’s as a deep a hurt as you can do, as deep a wound of trust as you can make.

O’Connor: The news is big in terms of it is acknowledging how big a problem it was over the past seven decades. But it’s also big because it’s really understanding: it had all of this information for seven decades. This isn’t something that it just uncovered by opening a file cabinet that had been lost for all this time. It has known this from the beginning.

Coyne: I think the wound of this is generational, I think it’s going to haunt us for decades still to come. And all we can continue to do as a church is do the right thing for the right reasons, one person at a time, it’s basically brick by brick.

O’Connor: On one hand, it is necessary for it to come forward and reveal this. And on the other hand, part of the horror of this whole issue is the fact that the church knew for seven decades exactly what was happening. And I think that’s why the revelation of it this week was so big. Because it really was the first time that people could understand just what the church knew, and just what it didn’t do about it.

You’ve looked over this report. Can you describe what it’s actually like? People are named in this — what level of detail does it get into about the allegations that have been leveled against them?

O’Connor: One of the challenges for the committee — it was a seven member lay-led committee — was, they wanted to get the names of the priests out there so people had a sense in terms of, was this priest in your parish? Was this priest in your community? Might someone in your family have known this priest and perhaps been affected by it?

But they also needed to retain the confidentiality of those who had submitted reports of abuse. So they could tell us, for example, that there were 40 priests, but they can’t tell us how many children were affected by this, or how many instances that each priest was reported to be a part of.

I think that there may be some frustration that there isn’t more of a sense in terms of what actually happened. I understand why they’re not reporting that, in deference to the accusers and to the survivors and wanting to maintain that confidentiality. It means that part of the story is still not public.

A lot of the conversation around this seems to focus on the legality of these accusations, and what potential litigation might come from this. And I’m curious, where do those things stand? What happens next, now that these names are out in the public?

O’Connor: What’s interesting is when the report was commissioned last fall, the statute of limitations for bringing forward a civil case was six years from once you understood that the diocese had information that they weren’t revealing, and as a result, abuse took place. Since the report was commissioned last fall, the Vermont Legislature has adopted a new law that says that there is no statute of limitation. You can bring a lawsuit at any time.

I want to be really clear about this. This is about civil cases, this is not about criminal charges. Most of cases that are being brought forward and have been brought forward since 2002 involve people suing the diocese for neglect in their hiring and supervising practices towards these priests. So they’re not actually suing the priest. They’re suing the diocese, saying you knew this was a problem, yet you continued to hire them, and you continued to let them work. And so that’s where the suits are coming forward.

The challenge for the diocese now is, under the old statute of limitation, you had six years from when you discover that the diocese knew what was going on to file your suit. So most of these cases were such that that six years has already passed. When the Legislature this spring adopted this new law that said that’s repealed, now you can bring civil case at any time. Suddenly, the diocese is looking at the possibility that a lot of people are going to see these names and say I was abused by that priest. And they’re going to come forward and sue the diocese, because they knew that this priest had a problem, and they didn’t do anything about it.

And that’s a direct result of this new law that wasn’t there last year.

O’Connor: Correct.

Coyne: We made the decision to publish this list before anybody knew the statute of limitations was going to be removed in the state of Vermont in perpetuity, which just blows my mind in terms of justice, but we’ll do the best we can. But I want to give justice. If someone was abused, I want to give them the justice that they’re due. And I’ve tried to do that since I’ve gotten here.

O’Connor: At this point, Jerry O’Neill, who is a Burlington attorney, and has covered about 50 of these cases for accusers in the past two decades, has another six pending cases. My guess is because of this press conference that took place on Thursday, he’s going to get more phone calls about people who were interested in pursuing their own lawsuits.

Bishop Coyne acknowledged in the press conference, and then again, when you were talking to him afterwards, that there’s a limited amount of money for the diocese to settle cases or to hire lawyers and go to court with some of these cases. What does that mean for them? Like, what is the outlook, big picture here, in terms of the consequences of putting this information out there for them?

O’Connor: I do think that the fact that they put the list out does bring more attention to it, does make people start thinking, hmm, is this something that I do want to pursue legally? That said, they’ve had a lot of publicity over this on the last 20 years, and a lot of people have already come forward. So I do think that might there be a possibility of new lawsuits? Yes. Do I see a tsunami of them? Not necessarily.

I also think the challenge in terms of people who are coming forward is, if you are looking for a settlement, you’ve got to be able to work with a diocese that has pretty much sold off most of its assets.

Coyne [in conversation with Kevin O’Connor]: With the removal of the statute of limitations, I think it’s going to be much more difficult for us to settle cases, because where do you start? And eventually we’re gonna run out of funding. So I’m hoping to avoid it, but I think we might have to go to litigation. And then we’ll probably lose, because we don’t, you know, these cases are hard. And people have a lot of sympathy for the victims and all that it’s hard for us to prove that, you know, that we’re not liable. And, you know, a lot of times what’s happened is people will say, well, you may not be liable in this case, but you are liable and a lot of other ones, so we’re going to find…

O’Connor: The difference I’m hearing though, is if you went to court, it would not be because you’re contesting the claims, as much as you can’t settle for the amount that’s being requested.

Coyne: And if they come back and they say the settlement we’re fining against church racks millions of dollars, then we can say we don’t have it. And then where do we go from there? And then we also think we can appeal. We can’t appeal until we lose. And we feel that there’s, you know, this possibility of being able to appeal the justice and removing the statute of limitations in perpetuity because it doesn’t allow us to make a just defense.

O’Connor: This has been a conversation that has happened in the past. I know it happened in 2002, when all of this first started coming out because of the Boston Globe, it’s happened every time there was a big verdict in Chittenden Superior Court over the years, there was sort of this conversation of what is this going to lead to. And I think in the end, a lot of the people who are bringing cases forward are concerned less about the money, and more about simply having acknowledgement that it happened. There are going to be people, I think particularly because of the Me Too movement, who are now starting to feel comfortable saying, I can come forward, I can talk about it, in a way that you might not have felt comfortable about 20 years from now or even five years ago.

So I think that’s going to be the question is: How many more people will now come forward? And I don’t have the answer to that. And I was talking to Jerry O’Neill, the lawyer, as I said he’s got about six pending, but I think both for him and the bishop, it’s a question of who will come forward.

It’s interesting, too, to hear Bishop Coyne, he even talked about it today — he’s fairly open about acknowledging that there has been this sense of shame on people in the past to report that. And he seems willing to acknowledge that that was kind of the fault of the church itself, making people feel ashamed to come forward and acknowledge allegations like this.

Coyne: The victims of these priests are still bearing the wounds of what happened to them. Until now, the scope of all this has been our family secret. Family secrets can be toxic. Harmful past experiences unspoken, unaddressed and known only by a few, fester like neglected wounds. The innocent victims of the family of the family secrets are often made to feel ashamed about what happened because no one listens to them, or even sadly, at times, believes them. While these secrets remain hidden, those who have been hurt are often unable to find the healing they need, especially if those who are harmed them are still part of the family, even if in memory. The church is not immune from this.

O’Connor: I think what’s interesting about this is when this was reported by the Boston Globe in 2002, was the first time that these kind of allegations were really put out there publicly. And I think both the church, but I also think the press and society, is starting to learn with how you talk about this thing. In the past, it wasn’t something that was talked about. So I think everybody had difficulty with it.

I know that the press, for example, when I started reporting this back in 2002, there were real questions. Do you put this out there? Today, it makes perfect sense. Well, of course, you’re going to report this out there. Back in 2002, when we started reporting some of these cases, we got a lot of pushback. There were a lot of feelings that we were simply trying to damage the Catholic Church, that we didn’t actually have proof of this, people hadn’t come forward at the time. There was not an understanding in terms of if you are someone who has survived this, that you wouldn’t necessarily come forward at the time, that there was such pressure to keep things quiet.

I think it’s only been as time has progressed, that people understand just how difficult and just how nuanced this whole process is for a survivor in terms of when they take it in, when they are actually able to not only acknowledge it to themselves, but to close family members, let alone and go forward and bring it forward. So I think there’s just a lot more knowledge in terms of this whole process now than there was when this first started being reported 20 years ago.

You talked about how, you know, since these huge initial revelations back in 2002, you’ve been covering this sort of steady drip, drip drip of information and new revelations about the church. Why? Like, why does this continue to be relevant after the sort of large-scale problem was already exposed to the public?

O’Connor: The challenge was, when the Boston Globe came out in 2002, with its report, on one hand, there were a lot of people who were surprised. And there was also a lot of denial, there was also a ‘we’ll take in part of this, but not all of this.’

I remember one of the first survivors that I talked to, in 2002 gave me a phone call. I was working in a newsroom in Rutland at the time, and he was getting really frustrated, because he felt like the public was viewing this in their minds as ‘oh, the priest, perhaps brushed their hand and appropriately against an altar boy, helping him get in and out of his robes.’ You know, ‘innocent, inappropriate, but…’

I think there was a real frustration among some of the earliest people to come forward, that people did not understand the extent of what actually happened. You can’t simply discount that as ‘touched him inappropriately, perhaps was trying to help him in and out of a garment’ or something like that.

These kids were sexually abused. And the challenge reporting that is, I know the lawyers know, I know, the diocese knows the specifics involving this. And they are so explicit and so graphic, that you don’t put that out there — only because it’s hard to read, and you don’t want to exploit the people who were abused.

At the same time, I know some of the survivors are in this odd position of wanting to maintain their dignity, and their confidentiality, and yet sometimes feeling like ‘people really don’t get the extent of what happened to me.’ I think it’s taken 20 years for people to slowly start to, one by one, understand the scope of this. To understand how all of this work.

Every time I would go to a different trial, there’d be questions, either amongst jurors, amongst some of the lawyers, in terms of, well, if this happened to you x number of years ago, why are you only telling us now? People are now starting to understand why people didn’t report that earlier. One of the biggest, in the past, arguments that the church would make, if someone would come forward and would be on the witness stand, they would say, ‘well, you say you were abused when you were 12. But then at 13, you started drinking and at 14, you started getting into drugs. And at 15, you started to get in lot of trouble. How can we trust you?’

That was the argument of the church. And that was actually a belief of a lot of people. ‘Yeah, how do we trust this kid? He’s saying he was abused at 12. But look what he did at 13, 14, 15.’ Not understanding the whole reason why he started drinking at 13, and using drugs at 14, and really acting out at 15, was because of the abuse. Because he didn’t know what to do with that. Because he didn’t feel that he could come forward to anybody. Who’s going to believe a 12-year-old kid versus the priest, who’s an adult, who’s revered by the community? So I think increasingly, people started seeing this differently — going from, ‘why should we believe them? Look what they did after the fact.’ To: ‘oh, in fact, maybe that is a symptom of the fact that it did happen.’

It does seem like now, there’s more widespread acknowledgement to the point where we’ve even got a church leader who’s standing up and reaching a certain level of acknowledgment. Do you worry that at this point, people have almost become desensitized to some of these reports of abuse from the Catholic Church to where things like this report today, they might be so unsurprised by it, that it doesn’t get the attention that it merits?

O’Connor: I think one of the challenges reporting it out is the fact that this scandal has been so widespread that this is not just a Vermont issue, this is not only a national issue, this is a worldwide issue. My ancestry is from Ireland — I have recently been over there and found that all of the headlines that we’re reading here in the United States, they’re also reading over in Ireland. So wherever there is a Catholic Church, this seems to be a problem. And unfortunately, this was dealt with the same way, wherever you are.

Part of the challenge on this thing is people are almost inundated with all of the headlines. That said, I think where it’s really hitting home is because it’s being reported locally. I think if you read about 1,000 priests in Pennsylvania, or x number of them nationally, it’s something that can go in one ear and out the other. I think when you actually start looking at a list that was presented by the Vermont diocese, and you can actually start seeing oh, that was a priest and they were in this particular parish, whether it was in Brattleboro, or Barre or Burlington, then it starts hitting home more, then you start actually sort of considering, ‘do I know someone myself? Do I have friends, do I have neighbors?’ So in a way, I think the reporting on the local level is where people actually start taking it in.

Thanks, Kevin.

O’Connor: Thank you.

Subscribe to the Deeper Dig on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, or Spotify. Music by Blue Dot Sessions and Lee Rosevere.