Editor’s note: David Moats, an author and journalist who lives in Salisbury, is a regular columnist for VTDigger. He is editorial page editor emeritus of the Rutland Herald, where he won the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for a series of editorials on Vermont’s civil union law.

The generational differences between younger left-wing Democrats who favor big, sweeping change and more practical-minded liberals who accept that politics requires compromise has been a theme of the presidential campaign. The clash between House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the four women who make up the so-called “Squad” has been framed in this way.

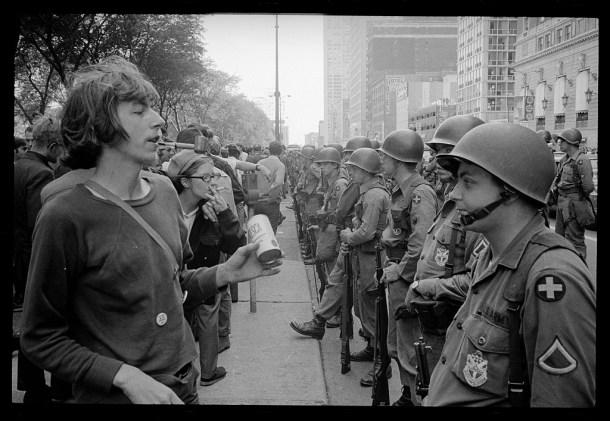

I am not part of the younger generation, but at one time I was. I saw a similar dynamic play out in the ’60s, and I took some lessons away from my experiences. Then and now, the younger generation was fed up with the corruption of the system — or the establishment, as it was called. And in both periods there was good reason to be fed up.

Back then the Vietnam War was a life-wasting disaster founded on lies and tainting the entire political and business establishment. When Dow Chemical, the maker of Agent Orange, came to recruit future employees at the campus where I was a student, it was a target of bitter protest.

Today the political establishment has been tainted by its subservience to corporate interests, which have produced the disaster of the Great Recession and the economic inequities that have been metastasizing for more than 40 years. And the refusal of business and government to face up to the reality of climate change threatens human survival. Why would radical change not be justified?

Sen. Bernie Sanders, the Vermont senator, is like a living time capsule from the ’60s. In his view, if the people would realize their own power to use government as a tool in the public interest, they could seize economic control from the corporations and oligarchs and take on the challenges of inequality and injustice.

Sanders’ rhetoric has scarcely changed over the decades. It still reflects the frustration and anger felt by the younger generation back in the ’60s, combined with a socialist slant inherited from the ’30s. What has changed is that economic and social conditions have become so dire that his diagnosis, if not his prescription, is more obviously apt. But as in the ’60s, the younger generation, fueled by a sense of anger and powerlessness, has turned at least a share of its wrath on an older generation of liberals who counsel patience and pragmatism.

I remember the anger and powerlessness many of us felt back then, which boiled over in 1967 when I had an encounter with Hubert Humphrey. It left a lasting impression.

Humphrey was vice president under President Lyndon Johnson, and before that he was an early champion of civil rights and a leading liberal in the U.S. Senate. In 1967 I was a college student with a summer job in Honolulu. The war was entering its worst phase, and it was an extraordinarily angry time. Many despised Johnson for what he had done, and for young people, lacking even the power to vote, our sense of powerlessness only fueled our anger.

I had attended meetings of a small anti-war group in Honolulu, and they planned to stage a protest when Humphrey came to Oahu to speak to local Democrats. The event took place at a compound on the windward side of the island, and the protesters were restricted to a small area across the road.

During the afternoon, there were speeches and politicking inside the compound while for hours about two dozen people carried signs and marched in a circle in the hot sun. As the afternoon wore on, we grew tired and increasingly angry. Finally, it was time for Humphrey to leave, and his car pulled up in front of the gate on the other side of the road from our group. When he emerged, he came around to our side of the car rather than getting in on the other side. At this point our frustration had reached such a peak that when we saw him, the group erupted in rage, screaming, shaking fists. Photographers snapped photos of our angry faces. Our anger was so extreme that if someone had bolted and tried to attack the vice president, who was only about five yards from us, the whole group might have followed. No one did. What happened was Humphrey smiled his wide smile, waved to us and got into the car.

I was shaken. I had reached into myself to find the worst insult I could hurl at him, and when I saw him, I screamed, “Liar! Liar!” I left the event convinced that the anger of a mob was a dangerous thing, and I never wanted to subject myself to it again. At the same time, I thought it was probably good for Humphrey to see the depth of that anger. In fact, he had become one of the many liars who were defending Johnson’s war policy.

It’s a harsh fact, nevertheless, that the disaffection of the younger generation probably cost Humphrey the election in 1968, leaving us with Richard Nixon. There were legitimate reasons for that disaffection, but for liberals to secure a win for Nixon by abandoning Humphrey was not exactly a gain for the nation.

One of Sanders’ weaknesses as a politician has always been his tendency to believe that anyone who disagrees with him or favors incremental rather than systemic change is a tool of capitalists or ideologically deluded. In the ’60s there were many dogmatists like that. The younger generation today, feeling the same sense of powerlessness and anger that we felt in the ’60s, has rallied to him because he brings the kind of ideological purity that seems like an answer. Why not throw out the entire health insurance industry at once and institute Medicare for All, right now? Just do it. Rally the people to your banner and do it.

Barack Obama, a pragmatist, found it was not as easy as that. Progressives grew frustrated with him because he was not bold enough. But Obama was president not just of New York, Massachusetts and California, but of Missouri and Montana, too. He had to bring along conservative Democratic senators. He got what he could get. Progressives might argue that he settled for less because he tried for less. This is the tension that now exists between Pelosi and the Squad.

Pelosi is a longtime liberal champion, probably more able than Humphrey was in his day and probably shrewder than Obama in his. The anger of progressives today ought to be directed, not against moderates in the ranks of the Democrats, but against those who today trammel the Constitution and vandalize the government. The Republican Party has subjugated itself to a demagogic fraud. Does he deserve to be impeached? Of course. But America is larger than the Bronx and Queens, the House district of progressive icon Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. The impeachment question continues to bubble because Pelosi has not been rash about setting out on that course. It may happen, but Democrats should not succumb to a litmus-test mentality — on impeachment, health care or any other issue.

The anger of the younger generation is as justified now as it was in the 1960s, but anger cannot govern. The election in 1968 was the first when I could cast a ballot, and I voted for Dick Gregory, the comedian, instead of for Humphrey. I thought I was sending a message; in fact, I was acting like an angry, self-indulgent jerk. It was Richard Nixon who benefited from my message, winning by the narrowest of margins. Ralph Nader and Jill Stein helped George W. Bush and Donald Trump in the same way.

Medicare for All and the Green New Deal are major components of the progressive agenda, and the Democratic candidates are trying to signal the degree to which they agree with these goals. Voters in Iowa may decide that a moderate like Sen. Amy Klobuchar is a more reasonable choice because she is not rigidly tied to the agenda but will pursue it as a pragmatist. Or they may favor someone like Sen. Elizabeth Warren or Sanders, who have portrayed themselves as more progressive and more ideologically committed. Or a shrewd candidate like Sen. Kamala Harris may try to have it both ways, signaling that she is progressive but leaving room to convince general election voters that she is really a pragmatist.

For Ocasio-Cortez and her cohort of young progressives, Pelosi is their best ally. She is not going to sell them out. She is going to save them from themselves and remind them that voters in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan and Florida must be part of their broad coalition.

Anger like that which we felt on Oahu all those years ago creates the illusion of pure, honest emotion, but it can also drive people away and divide and destroy. Anger is a reality that must be heeded, but statesmanship like that of Obama or Pelosi has a more inclusive task, taking into account the larger reality of a large, diverse nation.