Editor’s note: Mark Bushnell is a Vermont journalist and historian. He is the author of “Hidden History of Vermont” and “It Happened in Vermont.”

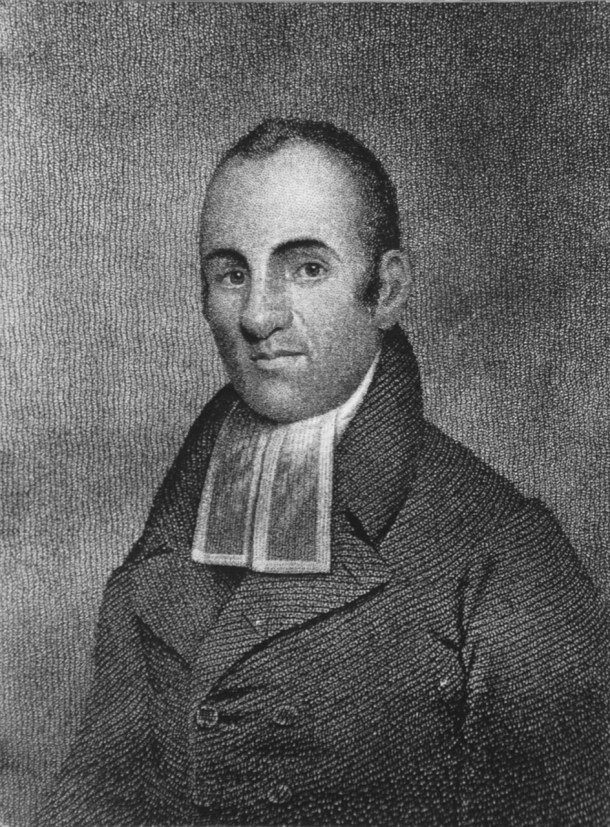

To say the odds were stacked against Lemuel Haynes from birth is an understatement. Here are some of the obstacles that stood in the way of his eventually finding his calling as one of Vermont’s—indeed New England’s—most highly regarded preachers: First, he was illegitimate. His birth July 18, 1753 in West Hartford, Connecticut was the accidental result of a tryst. Second, he never knew his father, whose name has been lost to history.

Third, he never really knew his mother, either. Her identity has been debated for 2 1/2 centuries. One theory is that she was a Scottish immigrant servant named Lucy Fitch who worked for the Haynes family of West Hartford. Others suggest that Fitch was merely a convenient (and perhaps not entirely willing) stand-in for the boy’s true mother. According to this theory, his mother was a Goodwin, a member of a prominent Hartford family who had sought refuge from scandal in the Haynes household.

Fourth, on the baby’s birth, people learned that the father was black. The baby could have been born in worse situations at the time—New England was, by colonial American standards, a tolerant place—but his mixed-race parentage would forever be a burden.

After Fitch attested she was the mother, the Haynes family fired her. As a way to give the boy a respectable name, or as revenge against her former employer, she gave the baby the last name of Haynes. So it was that Lemuel Haynes greeted the world.

No one seemed to want this unintended baby. Fitch left him behind when she left the Haynes house. The Hayneses didn’t want to raise him either, so they gave him to a farming family, the Roses. They were traveling through West Hartford on their way to settling in the town of Granville, Massachusetts. He wasn’t treated like family; he was made an indentured servant until he turned 21. But critically for Haynes’s future, the Roses treated him as one of their own in terms of education. They encouraged him to read and study whenever he found the time, and they sent him to school with their other children on the rare occasions they attended classes.

The head of the household, Deacon David Rose, learned to rely on Haynes’s intelligence and judgment. By the time Haynes was a teen, he was entrusted with the difficult task of dealing with horse traders, and at many Sunday dinners, he was called upon to restate the sermon he had heard that day for the benefit of family members who attended another church.

Just as Deacon Rose came to appreciate his surrogate son, Haynes learned to admire the deacon’s devotion to God and sought to emulate it. Haynes’s religious fervor was coupled with fear – the fear he would die a sinner. One night, he saw northern lights and dreaded they foretold Judgment Day. “For many days and nights I was greatly alarmed for fear of appearing before the bar of God, knowing that I was a sinner,” he later wrote. Soon afterward, he had himself baptized.

After turning 21, Haynes left Granville to serve briefly as a minuteman in the Boston area at the start of the Revolutionary War. In 1776, he helped reinforce Fort Ticonderoga against a feared British attack, which didn’t end up coming until the next year, after Haynes had returned home to recuperate from typhus.

Haynes focused again on religion, studying Greek, Latin and sermon writing with a pair of ministers in Connecticut. He completed his studies in 1780. Immediately, the parishioners of a new Congregational church in Granville called him to be their preacher, making him the first African American ever to lead an all-white congregation. Five years later, he became the first black person ordained by any religious organization in North America.

Haynes’s position as preacher soon offered him further recognition from the white community. One of his parishioners, Elizabeth Babbit, became an admirer and asked him to marry her. His being part black made it impossible for him to ask her. After consulting his fellow preachers to gauge the reaction of other whites, Haynes accepted.

He soon had another proposal to ponder. In 1787, Haynes had served on a preaching circuit that took him into what was then the Republic of Vermont. His firm and ardent sermons caught people’s attention. Whether out of racial tolerance or due to the shortage of preachers on the frontier, the members of the West Parish congregation in West Rutland asked Haynes to lead them. Haynes would lead them for 30 years.

That didn’t mean he would find universal acceptance. One church member years later recalled being taunted by boys from another church who mocked Haynes with racial slurs. Despite whatever insults he endured, Haynes was a success. Under his leadership, the West Rutland congregation grew from 46 members to more than 300. People remembered him for his quick, if sometimes acerbic, wit. When another minister’s papers were lost in a fire, Haynes supposedly suggested they had produced more light in the blaze than they ever had from the pulpit. Another time, two boys shouted to him in the street, “Father Haynes, have you heard the good news? The Devil is dead!” Haynes patted the boys on the head and said, “Oh, you poor fatherless children! What will become of you?”

But in church, Haynes seldom joked. An acquaintance said, “When he ascended the pulpit, it was with a gravity which seemed to indicate that he felt the amazing weight of his charge as an ambassador of God to dying men.” A fellow minister said, “His enunciation, though remarkably clear, was extremely rapid; a delightful flow of words and thoughts, as if they were crowding each other for utterance.”

That “delightful flow of words” won Haynes admirers throughout the Northeast. He was regularly invited to be a visiting preacher or to deliver a sermon on Independence Day or George Washington’s birthday. He received an honorary master’s degree from Middlebury College and authored a widely read attack on Universalism and its belief in universal salvation.

After three decades of leading his West Rutland congregation, Haynes sensed he was no longer wanted. He submitted his resignation, and the congregation accepted. Haynes later explained to a friend that after 30 years, his congregation had discovered it had a black preacher. Although racial prejudice might have been the cause, it also might have been a case of a preacher and his congregation growing apart, a common occurrence in early America. Haynes’s old-fashioned political and religious beliefs, particularly that only a select few would attain salvation, were at odds with those of the new, younger members of his congregation.

After departing Rutland, Haynes finished his career with a three-year stint in Manchester and another 11 years in South Granville, New York, just over the border from West Pawlet.

Haynes fought his entire life to overcome the disadvantages of his obscure birth and racial prejudice. Despite those struggles, he eventually found broad acceptance in the white world. Perhaps fearing losing that acceptance, Haynes seldom spoke on the most important racial issue of the day: slavery. Although he avoided the subject of race, Haynes’s prominence made people in the white community confront the issue at some level every day. As one scholar suggested, his very presence and example made those he knew “better Christians” and better people.