[W]hen University of Vermont professor Emily Bernard talks about being black in the second whitest state in the nation, she often surprises people by starting with the positives.

“I bragged when Bernie Sanders, then a member of the House, called a meeting for people of color at a church in downtown Burlington purely to find out how we were faring,” the 51-year-old Nashville native recalls. “I called my parents to gloat when Vermont came in first on the nights of both elections that made Barack Obama president.”

The Green Mountain State, just four-tenths of a point less white than Maine’s 93.6 percent, also is one of the few where no black men have been killed by police during traffic stops.

“But Vermont, like any place, is complicated,” Bernard continues. “Perhaps the reason why no black men have been killed by police during traffic stops is because there are few black men here in the first place.”

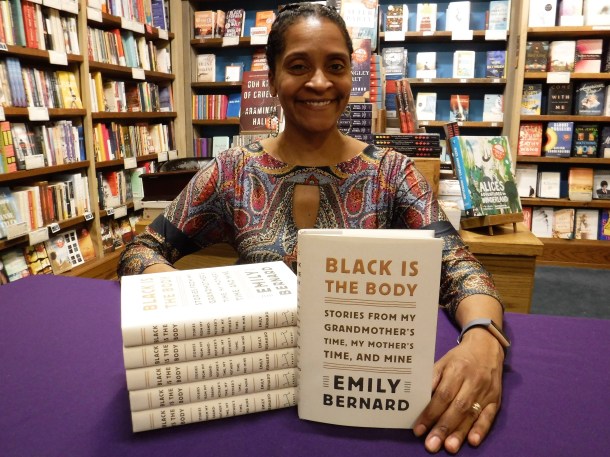

Addressing race, the English professor has learned, isn’t as simple as black and white. That’s why she’s receiving national recognition for her nuanced exploration of the topic in the new memoir “Black Is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother’s Time, My Mother’s Time, and Mine.”

“Each essay in this book was born in a struggle to find a language that would capture the totality of my experience, as a woman, a black American, a teacher, writer, mother, wife, and daughter,” the South Burlington resident writes in the introduction to her 240-page Knopf hardcover. “I wanted to discover a new way of telling; I wanted to tell the truth about life as I have lived it.”

Ask most Americans what they know about Vermont and race and they may point to recent late-night television skits poking fun at the state’s lack of diversity or all-too-real headlines about harassment that sparked former Bennington Rep. Kiah Morris to resign as the state’s only black female legislator.

Bernard knows the two poles — as well as all the places in between.

“Bernard’s well-crafted narrative is informed by an ethnographer’s eye, traversing the religious rituals of her black family in Tennessee, the eating habits of her Italian-American husband and the racial grapplings of her white university students,” the New York Times notes of the memoir Oprah Magazine deems one of “the buzziest books coming out in 2019.”

“At a time when Americans appear to be isolating themselves in their identity groups,” People magazine adds, “author Emily Bernard’s new book shows us that we’re not so different after all.”

Bernard was first inspired to write while recovering from surgery after she was attacked as a graduate student at Yale University a quarter-century ago by a stranger wielding a hunting knife.

“The man who stabbed me was white,” she writes. “I was not stabbed because I was black.”

Bernard instead was one of seven coffee-shop patrons in the wrong place at the wrong time.

“A friend, a writer, came to visit me in the hospital and suggested not only that there was a story to be told about the violence I had survived,” she recalls, “but also that my body itself was trying to tell me something, which was that it was time to face down the fear that had kept me from telling the story of the stabbing, as well as other stories that I needed to tell.”

Bernard went on to publish her first personal essay, “Teaching the N-Word,”, shortly after starting work in Burlington.

“We talk about the word, who can say it, who won’t say it, who wants to say it, and why,” it begins. “Here at the University of Vermont, I routinely teach classrooms full of white students. I want to educate them, transform them. I want to teach them things about race they will never forget. To achieve this, I believe I must give of myself. I want to give to them — but I want to keep much of myself to myself. How much? I have a new answer to this question every week.”

Bernard would go on to chronicle other complexities, be it her marriage to a white man, fellow UVM English professor John Gennari; the adoption of their twin Ethiopian daughters Isabella and Giulia; or her friendship with white women such as Manchester counselor Loree Zeif.

“These stories grew into an entire book meant to contribute something to the American racial drama besides the enduring narrative of black innocence and white guilt,” she writes. “That particular narrative is not false, of course, which accounts for its endurance, but there are other true stories to tell, stories steeped in defiance of popular assumptions about race, whose contours are shaped by unease with conventional discussions about race relations.”

That said, the woman who has lived in Vermont nearly two decades still asks herself, “Can I make a home here?”

For every positive Bernard cites — “incidents of racism that might be dismissed in cities with a higher percentage of African Americans are treated seriously here” — she can counter with a negative — Vermont, for example, has the nation’s third highest rate of incarceration for blacks, who are 85 percent more likely to be stopped by police than white counterparts.

“My daughters’ bus driver and I trade book recommendations in the morning as the girls clomp up the stairs to their seats: Stay,” she writes. “In the parking lot of the grocery store, a white man with a slick bald head looks at me, at my license plate, and then shakes his head in disgust: Leave. A thrilling early-winter snowfall: Stay. A long, bitter spring of stomping through the slushy, dingy remains of that same snowfall and its successors: Leave.”

Bernard’s book tour is a similar push and pull. Having launched the memoir with readings in Burlington and Manchester, she’s now traveling to such places as her roots in Nashville and a Harper’s Magazine event in New York before returning for public programs at the Norwich Bookstore March 27, Woodstock’s Bookstock in July, South Hero Library’s annual talk in August and the Brattleboro Literary Festival in October.

“It took me a long time to figure out what the book was about,” she told a capacity crowd in Manchester. “I was reading a lot of stories about race that were exclusively about conflict. None of us is one thing. We all live in complex ways. I wanted to write a book that would honor all of them.”

Bernard knows some authors of color, angry with the status quo, are preaching confrontation. But happy to see her book go into a second printing immediately upon publication, she’s aiming to promote a different conversation.

“We have to increase our connection with each other,” she says. “I tell stories and you’re free to take the lessons where you will.”

“I am most interested in blackness at its borders, where it meets whiteness, in fear and hope, in anguish and love, just as I am most drawn to the line between self and other, in family, friendship, romance, and other intimate relationships. Blackness is an art, not a science. It is a paradox: intangible and visceral; a situation and a story. It is the thread that connects these essays, but its significance as an experience emerges sometimes randomly and unpredictably in life as I have lived it. It is inconsistent, continuously in flux, and yet also a constant condition that I carry in and on my body. It is a condition that encompasses beauty, misery, wonder, and opportunity. In its inherent contradictions, utter mysteries, and bottomlessness as a reservoir of narratives, race is the story of my life, and therefore black is the body of this book.”

— Excerpt from Emily Bernard’s “Black Is the Body”