Editor’s note: Mark Bushnell is a Vermont journalist and historian. He is the author of “Hidden History of Vermont” and “It Happened in Vermont.”

Lawmaking often gets likened to sausage-making – something that becomes less appetizing the more you know about it. Some people just don’t handle power well; they let ego, ambition and acrimony obscure what should be a loftier goal.

It is only fitting, then, that the construction of the Vermont State House in the late 1850s was a similarly unpleasant spectacle to behold. Given the bitter feud that erupted between the architect and the superintendent of construction, it is something of a miracle that the finished building came out so well.

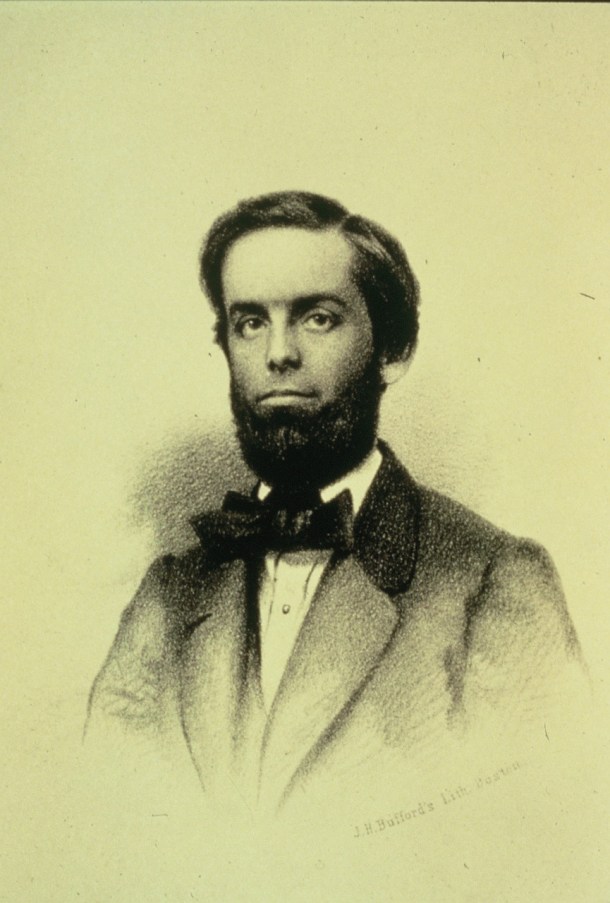

The selections of Thomas Silloway of Boston as architect and Dr. Thomas Powers of Woodstock as superintendent of construction must have seemed the perfect pairing. The two had recently worked together during the construction of the Windsor County Courthouse in Woodstock.

Silloway, though only 30 years old, had worked with Ammi Young, designer of the previous State House, which had been built during the 1830s and destroyed by fire in 1857. This time, Young was unavailable. His career had blossomed and he was busy designing custom houses and courthouses for the federal government. Silloway was a logical stand-in.

Powers was a physician who had served as speaker of the Vermont House. He was hired because he was seen as an able administrator, not because he was an expert on construction.

The men’s challenge was to create a fitting home for the growing state government and to bring the project in at an acceptable budget. Oh, and make the building as fireproof as possible. In addition to replacing wooden features with cast iron and brick ones wherever possible, the new plan moved the wood-burning heating system to a structure outside the building.

This would be Vermont’s third state house. The original had been a small, wooden structure sited roughly where the Vermont Supreme Court building stands today. But when the Vermont Constitution was amended in the 1830s to add a state Senate, the building was no longer large enough. Young designed a large granite state house with a columned Greek portico and topped with a modest, flattish dome. When fire claimed the second State House, Silloway created a replacement that would sit in the same location and resemble Young’s design in many ways. However, Silloway extended the building’s wings and made the structure deeper and taller.

The biggest change Silloway made was adding a large, ornate dome. Arguments over how to support such a massive feature would drive a wedge between Silloway and Powers. The feud is detailed in “Intimate Grandeur: Vermont’s State House,” written by Nancy Price Graff with state curator David Schutz.

Relations between Silloway and Powers started well. In October 1857, Powers praised Silloway’s work in a report to the committee overseeing construction, thanking him for his “very valuable professional services.” Powers particularly liked that Silloway had added windows, which he said would “relieve the new building to a great extent of that prison-like aspect” of its predecessor. Silloway’s design was “magnificent,” in Powers’ opinion. The building would provide a suitably majestic home for Vermont’s legislature.

But something happened in the ensuing months to sour the men’s relationship. Powers began to worry the project would cost too much. He also feared that the 100-ton dome wasn’t sufficiently supported in the plans. He may have had visions of how the dome of the previous State House had collapsed so spectacularly during the fire.

Silloway said he wanted to travel to Montpelier in May to oversee construction of the roof and dome. Powers rejected the request, citing what he said was the needless expense of transporting, lodging and feeding the architect when Powers could do the work himself.

Silloway complained in a letter to construction committee member George Perkins Marsh of Woodstock. Marsh, a diplomat and scholar who would become an early environmentalist, kept this letter and nearly 50 others that Silloway wrote him during construction of the State House. The letters can be found online on the University of Vermont’s Digital Initiatives website.

Silloway wrote Marsh that he had managed to meet with Powers but found him “the same, as he was—entirely confident that he is the all.”

In his defense, Silloway called on the contractor who had overseen construction of the second State House, Nathaniel Sherman of Plainfield. Sherman signed a statement that Silloway quoted in a letter to Marsh. In it, Sherman noted that if the architect isn’t present during construction, “mistakes must inevitably occur, and the building be unscientifically constructed.” In other words, Sherman was concerned the building wouldn’t be properly engineered.

Powers apparently realized that he needed an architect’s help, but for some reason he didn’t trust Silloway. When Silloway threatened to resign if he wasn’t allowed regularly on site, Powers refused to back down. Instead, to the astonishment of Silloway and Marsh, he replaced Silloway with another Boston architect, Joseph Richards, to finish the project.

Silloway had already addressed the issue of how to support the dome by working with a master carpenter to design and build a truss system. In fact, Silloway published a book that year, entitled “Text-Book of Modern Carpentry,” which included sections on the tensile strength of lumber, the building of truss beams and how to frame a wooden dome.

But Powers had the trusses disassembled and rebuilt according to Richards’ design, eliminating an elegant feature. Silloway’s plan for each of the elaborate spiral staircases would have allowed space for a small, domed skylight, covered in colored or frosted glass, which would have brought light into the building from the dome’s windows. When the skylights were scrapped from the project, the building lost its only interior clue that it was surmounted by a great dome.

Richards and Powers also simplified the design of the interior plasterwork and the staircases leading to the third floor.

Silloway had little recourse other than to write Marsh. “Powers begins to show sines (sic) of relenting,” he wrote optimistically in August, “and may he relent more till he concludes to go to Woodstock and let things alone for which he has no knowledge or affinity (sic).”

Powers defended his actions in a report to the Legislature in which he tried to take back all his previous praise for Silloway, whose “judgment and experience,” he now wrote, “have not equaled his zeal.”

The Legislature appointed a committee to resolve the scandal. The committee came down strongly in Silloway’s favor. It criticized Powers for many of his decisions, including reusing damaged columns from the previous State House in the new portico, removing the skylights from the design, placing an unattractive furnace chimney by the east wing instead of behind the building, and dismantling Silloway’s trusses without even testing their strength.

Despite his best efforts, Silloway never regained control of the project. The State House we know today reflects his vision for the exterior, but the interior is a mixture of his vision and Richards’. To give Silloway his due, or perhaps to prevent a lawsuit, the Legislature declared that in any official documents, if any architect was named, Silloway had to be credited.

Silloway must have taken some solace from the public reaction after the new State House opened Oct. 13, 1859. The Boston Journal reported that “(a)ll Vermonters are proud of it, and they have the right to be, for it is, without doubt, the best State Capitol in the Union.”

Many Vermonters still feel that way, even if they don’t always want to watch the sausage-making that sometimes occurs within its walls.