[G]ov. Phil Scott’s plan to fund the long-term cleanup of phosphorus-laden Vermont lakes will require tapping more than $114 million from the state’s general fund over the next five years.

Lawmakers are concerned that diverting revenues that ordinarily would go to the general fund will leave a hole in the budget and amount to “robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

The governor has proposed using revenues from the estate tax — $8 million next year and as much as $13 million in years to come. In addition, Scott would continue to finance clean water initiatives with the property transfer tax.

Some Democratic lawmakers and environmental advocates have questioned Scott’s plan. They are concerned that shifting money away from the general fund will hurt other programs. Administration officials counter that the economy is expected to grow enough to absorb the financial hit.

In his recent budget address, Scott asked lawmakers to consider the entire “packaged concept.” The estate tax threshold would go up, in line with other states, which the governor hopes will give Vermonters an incentive to retire here.

“Vermonters impacted by this tax are well-advised from tax professionals, and they are highly mobile,” Scott said. “If we can come together, this change will help keep more of these taxpayers here and support a legacy of clean, healthy lakes, rivers and streams, all at the same time.”

Scott’s proposal comes at time when Vermont remains under federal pressure to clean up several bodies of water, including Lake Champlain, Lake Carmi and Lake Memphremagog, where toxic algae blooms have frequently occurred. The Legislature asked the Scott administration to come up with new revenues as part of a long-term funding plan; the governor’s office instead relies on existing general fund resources for cleanup projects.

Vermont must come up with $2.3 billion over the next 20 years to comply with federal pollution reduction orders. Excess phosphorus is the main cause of the cyanobacteria blooms. The EPA has ordered that the surrounding watersheds lower phosphorus pollution coming into the lakes. Meanwhile, the eastern half of the state must lower nitrogen in runoff going into the Connecticut River to improve water quality in Long Island Sound.

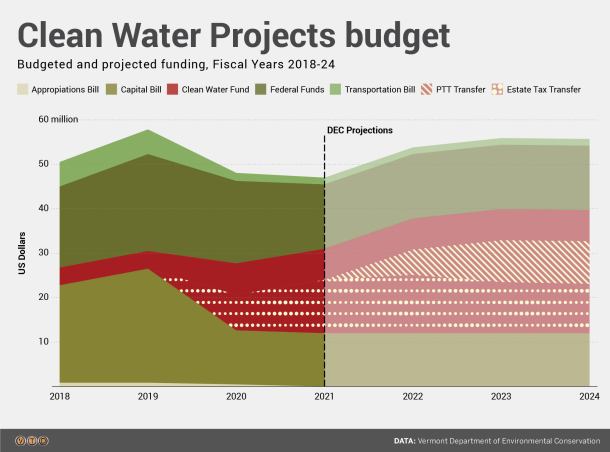

Since the 2015 passage of Act 64, Vermont’s Clean Water Act, the state has used short-term sources — like appropriations from the capital bill — for the majority of its share of the funding.

Last year, the EPA gave Vermont a “provisional pass” on its Lake Champlain report card for not identifying a long-term clean water funding source. In a 2017 report, Treasurer Beth Pearce said that the state needs to identify a new revenue source that would provide $25 million annually for clean water projects.

Scott’s budget proposal next year calls for a total of $48 million for clean water efforts, such as better management of the state’s 7,000 miles of dirt roads and on-farm water quality projects. That total includes more than $19 million in federal funds. The annual amount of money needed for clean water funding will increase to $50 million to $60 million per year by 2024, according to the administration.

Under Scott’s proposal, all revenue from the estate tax will go toward clean water funding starting in fiscal year 2022. As part of the estate tax plan, the governor is also seeking to raise the threshold for the estate tax from $2.75 million to $5.75 million over four years, which will decrease average revenues from $20 million to $11 million a year.

Although the Scott administration change would reduce state estate tax revenues, the governor believes that in the long run the state will benefit from other taxes paid by aging residents who stay in Vermont.

Sen. Randy Brock, R-Franklin, a member of the Senate Finance Committee, said Scott’s estate tax proposal was “intriguing” and could prevent wealthy people from moving to other states where taxes are lower.

However, Sen. Ann Cummings, D-Washington, chair of Senate Finance, questioned whether the estate tax reforms would result in fewer wealthier Vermonters leaving.

“We’re trying to predict human behavior with tax policy, which — given that most humans make decisions on a number of factors, not just taxes — is risky,” she said.

The estate tax currently feeds into the state’s general fund, unless revenues exceed 125 percent of projections in a given year. In that case, anything above the 125 percent threshold goes into the state’s higher education trust fund to help pay for college scholarships.

Even with the infusion of revenue from the estate tax, the state’s clean water fund needs an additional estimated $5.7 million in 2022 and more than $9 million annually in future years, according to the administration.

The administration proposes closing that gap by allocating a portion of the property transfer tax that currently goes into the general fund, according to Julie Moore, secretary of the Agency of Natural Resources. Vermont currently levies a property transfer tax surcharge — which raises around $5 million a year — to help pay for clean water projects.

Reducing the state’s reliance on capital bill dollars, the practice during Scott’s first term, will provide greater flexibility for the broad array of clean water work needed, she added. Moore stressed that the diversion of funds to clean water programs will be phased in and the impact on the general fund, particularly when measured year to year, will not be too steep.

Adam Greshin, the governor’s finance commissioner, said in an interview that the administration’s proposal will not lead to a shortfall in the general fund. The general fund has benefited from a windfall of additional revenue this year spurred by economic growth and federal tax cuts. The administration is also proposing about $18 million in new taxes and fees this year, much of which will be funneled into the general fund next year.

“I don’t think there’s going to be any loss of revenue to the general fund — if anything there will be more revenue from initiatives coming from the governor’s budget,” Greshin said.

In an interview Wednesday, Scott was confident that revenues would increase to cover the estate tax revenues for clean water programs.

“At the bottom line, we’re bringing in more revenue than ever, so we are supplementing some of that,” Scott said. “I think it is a viable source and I believe it can work. It hasn’t gone toward anything (specific) in the past – it’s just been swallowed up.”

Some Democratic lawmakers are skeptical whether other programs will be shortchanged with the diversion of the estate tax revenues.

Sen. Chris Bray, D-Addison, chair of the Senate Natural Resources and Energy Committee, said in an interview last week that Scott’s proposal seemed like “robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

“It does not seem to fit the bill of being an adequate, sustainable, long-term funding stream,” he said.

Bray plans on introducing another clean water funding bill with a per parcel fee — an idea he pitched last year — which he says at $40 per property would raise more than $14 million a year.

Sen. Jane Kitchel, D-Caledonia, the chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, said she did not understand how the administration’s proposal would not impact other services.

“They’re saying give us the benefit of the doubt, it’s a form of trickle down economics,” she said. “And we need to feel comfortable that, in fact, we’re making decisions that don’t create a hole.”

“Last year, we did see some major redistribution or proposals to reduce services or benefits that we did not find acceptable,” she added.

Lauren Hierl, executive director of Vermont Conservation Voters, said she was “pleased to see” the administration agree with the need to develop a long-term clean water funding source, but had reservations about how the governor was trying to do it.

“We’re concerned about the estate tax … because it does appear to be unpredictable year-to-year and fundamentally just taking existing revenue concerns us because we’re unclear what programs are being cut or where are we taking that money from,” she said.

Scott acknowledged Wednesday that the current windfall in revenue could change in future years, but feels the state can “cross that bridge when we come to it.”

“I think we can live within our means,” he added.

Cummings questioned that approach.

“We have been on a starvation diet for 10 years since the recession,” she said. “There’s a limit to how efficient you can be.”