Editor’s note: David Moats, an author and journalist who lives in Salisbury, is a regular columnist for VTDigger. He is editorial page editor emeritus of the Rutland Herald, where he won the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for a series of editorials on Vermont’s civil union law.

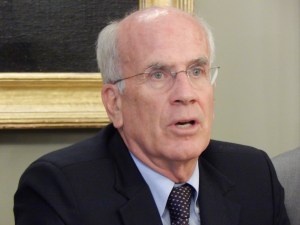

As the new Congress gathered in Washington last week Rep. Peter Welch of Vermont spoke of the excitement shared by Democrats, now a majority in the House, and also of the deepening apprehension about what he called the “stability” of the president.

Welch has never pushed the idea that President Trump should be the target of impeachment proceedings, saying that Democrats should instead focus on their progressive agenda. “The best impeachment is done by the voters,” he said last week.

But talk of impeachment continues as an ever louder hum of background noise, particularly since the criminal conviction of Michael Cohen, Trump’s former lawyer, who implicated Trump in his criminal activities.

According to Welch, much hinges on the investigation of special counsel Robert Mueller and two areas of inquiry: the possibility that Trump conspired with Russia to corrupt the 2016 election and the possibility of questionable financial links between Trump and Russia. Until Mueller weighs in on those questions, talk of impeachment is premature, in Welch’s view. But depending on what Mueller finds, everything could change.

Anyone who remembers Watergate knows that impeachment proceedings, once unleashed, dominate everything else. And yet, depending on what Mueller finds, impeachment may be “inescapable.” That’s the word used by Elizabeth Drew in The New Yorker, who was one of the leading journalists covering the Watergate scandal.

The issue of impeachment has grave and far-reaching implications for the constitutional order and the politics of the nation. We talk of the checks and balances built into the system — the executive and legislative branches balanced against each other and also checking one another’s excesses. Impeachment is a check so extreme that conviction of a president on impeachment charges has never happened in the nation’s history. That it is being discussed seriously in the third year of the Trump administration is an indicator of how alarmed many members of Congress, and the public, are at Trump’s behavior and history.

The constitutional and political implications of impeachment are always in serious tension. If impeachment were used as just another weapon of partisan warfare, a means for gaining advantage or punishing an opponent, the nation would be subjected to an unending round of attack and counterattack. The meaning of our elections would be destroyed if the winner could be tossed aside in cavalier fashion by the legislative branch.

Moreover, the political aftereffects of impeachment can linger in damaging fashion for many years, even in a case where the constitutional violations are plain to see. Richard Nixon resigned in disgrace rather than face impeachment, but even so, a remnant of revanchist Republicans continued to think he got a raw deal, a victim of a partisan conspiracy among Democrats and the media (the hated Washington Post!). An action as extreme as impeachment will inevitably breed an extreme reaction, and it has been said that at least some of the animus motivating the impeachment of Bill Clinton in the 1990s germinated during the Watergate scandal of the 1970s.

The Nixon case is instructive for what it says about the politics of impeachment and its constitutional significance. Much has been made in retrospect about the willingness of Republicans in Congress to abandon the president, but the Republican change of heart came late in the day. As revelations of criminal activity among Nixon’s closest associates metastasized, Republicans in Congress stuck with him, as did most of his supporters among the voters. After all, he had won a landslide election just two years before.

It was the glaring criminality evident in the White House tapes — and judicial decisions forcing their release — that showed the public that Nixon was guilty of high crimes against the Constitution. That is when Republicans decided Nixon had to go.

The only two presidential impeachments in U.S. history — of Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton — are less germane to the case of Trump. Johnson avoided removal from office by a single vote when the Senate refused to convict him on articles of impeachment approved by the House. Historians tend to view the charges against Johnson as trumped up, even if he was guilty of reprehensible policies obstructing Reconstruction in the South and siding with vanquished Confederates in the oppression of freed slaves. Impeachment is not meant as a vehicle for correcting policy — that’s what elections and the democratic process are for. Rather, impeachment is meant as a last resort when the Constitution is imperiled by a leader guilty of “high crimes.”

The impeachment of Bill Clinton on perjury charges related to a sex scandal were a mockery of the impeachment process. His transgressions — squalid as they were — did not involve high matters of state or constitutional principle.

But what if a president’s transgressions are so extreme that ignoring them threatens our constitutional system? It does not serve democracy to let a lawless president off the hook because it will stir anger on the part of the transgressor or of supporters unwilling to look at reality.

Because the bitterness and division provoked by impeachment may be so extreme, lawmakers are ordinarily cautious about proceeding in that direction. Welch’s views are in line with those of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the rest of the Democratic leadership. He believes events now favor the Democrats, even without talk of impeachment. He said the 2018 election represented a “repudiation of Trump,” affording Democrats a chance to win back the voters’ trust. He said voters could “finish the job in 2020.”

In the meantime, Mueller’s work continues, and the seriousness of the issues he is exploring have kept talk of impeachment alive. No one knows what evidence he has or what the rogue’s gallery of witnesses he has been speaking with has told him. But the web of ties between Trump and Russia, combined by his bizarre deference to Russia and its leader, Vladimir Putin, has raised many red flags. That his close associates felt compelled to lie about their contacts with Russians is noteworthy. That Trump pursued business interests in Russia during the 2016 election is interesting. That his foreign policy choices — erratic and alarming — align with the policy aims of Russia is troubling.

Welch raised the issue of Trump’s fitness for office and the possibility that provisions of the 25th Amendment could be invoked to remove him, which points to the general uneasiness about Trump’s ability to do his job, even if the 25th Amendment would be a reach much more unlikely than impeachment.

Congress, meanwhile, has convened, with a new Democratic majority in the House. What if Trump himself were to be subpoenaed to testify in a criminal trial brought against his son, Donald Trump Jr., or another close associate? The possibilities for chaos are endless. Everyone is awaiting the Mueller report. That is when talk of impeachment may get real.