The Deeper Dig is a weekly podcast from the VTDigger newsroom. Listen below, and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Spotify or anywhere you listen to podcasts.

[A]s state officials have worked to expedite an expansion of Vermont’s mental health system, the problems on the ground have not improved. Mental health patients face increasingly long stays in hospital emergency rooms while they wait for openings in psychiatric facilities.

New state inspection reports detail the serious deficiencies in treatment that those patients face: 18 regulatory violations over the past nine months describe incidents where patients were injured, forcibly medicated, improperly restrained or intimidated by law enforcement.

“I have a range of reactions,” says Mourning Fox, the interim director of the state’s mental health department, about reading those reports. “Anything from, ‘Wow, that’s unfortunate,’ to, ‘Oh my god, I can’t believe that.'”

Fox says his department alone can’t solve the capacity issues in the system: hospitals and designated agencies need to be proactive about solutions. “It has to be a partnership.”

Some hospitals that have been cited for violations, like Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital, are already adding specialists and redesigning their emergency departments to better accommodate psychiatric patients. But administrators say those steps alone won’t solve the systemic issues that prevent patients from receiving coordinated care.

Meanwhile, patients seeking immediate treatment are left with few options. Phoebe Sparrow Wagner, a poet and artist who has been treated for schizophrenia, says her experience in Vermont’s mental health system was worse than the illness itself.

“I’ve experienced horrendous things,” she says of her symptoms. “But frankly, the worst of it has been my treatment.”

Wagner says that over a series of hospital stays, she was medicated against her will, forcibly restrained, and placed in seclusion rooms. She’s found relief at Alyssum, a hospital diversion service based in Rochester, which she says is the type of program the state should expand.

On this week’s podcast, Wagner describes her experience being stuck inside the state’s overtaxed mental health system. Mourning Fox discusses the solutions the state — and other stakeholders — are working to pursue. And VTDigger’s Mike Faher recaps his reporting on widespread failures in patient safety.

[showhide type=”pressrelease” more_text=”Read full transcript” less_text=”Hide full transcript” hidden=”yes”]

Wagner: If you pass me the green book? Yeah, that one.

Just a heads up, our story today contains some brief but graphic descriptions of violence, including self harm.

Wagner: “Poem in Which I Speak Frankly, Forgive Me.” And the little epigraph says, “Gomer is ER speak for a troublesome, unwanted person in the emergency department, an acronym for Get Out of My Emergency Room. Gomer.”

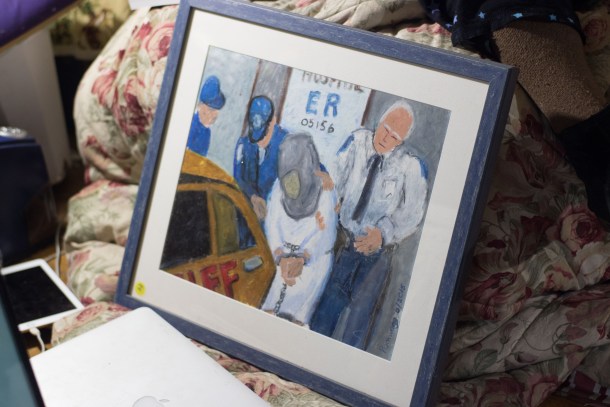

This is Phoebe Sparrow Wagner. Phoebe is an artist and a poet. And a lot of her work depicts her experience as a psychiatric patient in Vermont.

Wagner: So many times, gurneyed in by ambulance and police escort, dangerous to self or others and too psychotic to cooperate or scribble consent, you suspect by now that you were just a Gomer to the snickering scrubs in the ER who whisk you in back with the other disruptives lying in bed waiting for beds…

Mike Faher: She’s very frank and very open about her feelings about the mental health treatment system. She doesn’t feel it’s adequate in any way. And I found her stories about emergency department treatment to be really entirely in line with some of the reports that I’m reading, unfortunately.

Mike Faher has been reporting on the mistreatment of patients in the state’s mental health system.

Faher: So these are reports from the state Division of Licensing and Protection website, and the Division of Licensing and Protection goes out and performs inspections of healthcare facilities, and oftentimes these are inspections that are in response to complaints that patients have made. Sometimes the division says no, everything’s fine. Sometimes they say, yep, we found some issues and here’s what the hospital has to do to correct them.

In looking at them, I didn’t go into these documents with any preconceived notions, I just wanted to see what the state had come up with, and I was immediately struck by the sheer number and severity of mental health-related violations that had occurred at hospitals this year. I think there were something like 13 or 14 reports total from hospitals that had found problems, and of those, eight or nine of them were mental health related.

You had a mental health patient who was a juvenile repeatedly trying to escape and then successfully escaping from St. Johnsbury Hospital in March with no coat, and disappearing for 28 hours. You had a mental health patient who was combative and agitated getting into what I call honestly a brawl with hospital security and being tazed, again without being in police custody. You had repeated incidents of patients who were either improperly restrained to begin with or were restrained and those restraints were left on for too long. There are clear standards about how long you can restrain someone.

They’re actually put in handcuffs, or strapped down?

Faher: Well yeah, both. There’s sort of the hospital-type restraint, where your legs and arms are restrained, in some cases and this gets into another violation, you had law enforcement officers called in whether they were contracted security or just doing their jobs as police officers and handcuffing people who were not in police custody. And then at least in one case, those handcuffs were left on for a period of time. Again, someone who’s not in police custody. These were the type of things that we saw repeatedly throughout these reports.

Wagner: They restrained me for five hours because I was mute, and they wouldn’t let me out of restraints until I spoke, but I was unable to speak. They just believed that I was refusing to speak, so they kept me in restraints for five hours, even though I’d been lying still. That is illegal. You can’t tell somebody they have to speak loud if they’re mute, and they’ve been mute for days. I’ve been mute for months at a time.

Phoebe’s been diagnosed multiple times with schizophrenia. But she says that to her, that’s just a term used to describe experiences that other people don’t understand.

Wagner: I mean, the voices I hear, or used to hear — I don’t hear them so much anymore — were absolutely outside of my head. And as real as as you talking to me now. They would say things — just things like “burn, baby burn” would be a trigger for me to use a cigar on my skin. And at another time I had hallucinations of every sense, I could taste things, smell things that weren’t there, and then I was hearing things and, and I felt tactilely things. I had no way of knowing that these things weren’t happening. I just accused people of trying to poison me because food tasted bad and water tasted bad.

I’ve experienced horrendous things, but frankly, the worst of it has been my treatment.

Phoebe said that in her stays in Vermont emergency rooms and psychiatric facilities, she’s been forcibly restrained, placed in seclusion and medicated against her will.

Wagner: From the moment you are hospitalized behind a locked door that you can’t open and leave to go out and take a walk or have a cigarette, you feel trapped. You feel trapped, and you know who’s in charge and you know who’s in control. And if you have more sense than I do, you just simply comply for a few days and they’ll let you go. But I tend to not comply.

I had a friend who used to come into the hospital and she’d see me in restraints. She’d actually see me in restraints, and she’d walk into the room and they’d say, “Can you do something with her?” And then she did she tell them, “What have you done to her? What have you done to my friend?”

What, what’s going through your head when this kind of thing is happening to you?

Wagner: Nothing. Except… Nothing. Nothing. I just, well when when they took me out to the emergency room on a stretcher in this get-up, I was screaming my head off calling them rapists because I felt raped by their injection and the way they treated me. And I wanted to just shame them and embarrass them. Nothing justifies that kind of treatment of a human being, and I wasn’t charged with any crime, I wasn’t guilty of any crime, I wasn’t anything with any crime. I don’t even believe criminals should be treated that way, or people convicted of a crime should be treated that way.

Faher: We’ve seen a lot of statistics about the increasing number of mental health patients who are going to medical hospitals and getting stuck there because there are no inpatient beds for them. You sort of know in the abstract that it’s a problem. What these reports did to me was showed me that not only is this an increasing problem, it’s causing some very severe issues in terms of patient treatment in terms of the safety of patients and hospital staff, that there are real repercussions from these statistics that we’re seeing.

Mourning Fox: You know, I’ve seen all the ones that you folks have reported on, and then probably have seen others that weren’t in your reports, over the years. But depending on on the issue, I have a range of reactions, like you probably did. Anything from, you know, “oh that’s unfortunate,” to “oh my god, I can’t believe that.”

This is Mourning Fox. He’s the interim commissioner of the state’s mental health department.

Fox: We’re the perfect place for people to come in, we’re just not the perfect place or even a good place for people to remain. The emergency room is meant as a triage and you know, someone comes in, we triage, we provide those supports that they need to be stabilized, and then they move on. An emergency room is not, you know, a cardiac unit. It’s not an orthopedic unit. It’s not an OB-GYN unit. And it’s not a psychiatric unit.

Before Fox took over the department this year, he was the director of care management, which he describes as sort of like air traffic control for mental health patients. He took on that role right as the system’s capacity issues started to become obvious.

Fox: When there’s one or two new people who are in need of a hospital bed on any given day, that type of number is something that our system does absorb pretty well. You know, there might be a short stay, a few hours, maybe a day, but when there’s beds available and, you know, we’re having just, you know, one new person presenting kind of a day, the system absorbs that. When we have six to eight new people in a given day, that’s when the log jam starts to happen. It takes time for the system to recover from that.

Faher: I had a few folks tell me that it’s not a bad thing, it’s not necessarily a bad thing that if you’re having a crisis, that you seek emergency help, and a lot of places, especially in Vermont, where there’s not a lot of healthcare facilities, you would go to the ER. You would seek that help, and in an ideal world, you go to an ER and you’re assessed quickly, and it’s determined that you need, let’s say inpatient, maybe involuntary inpatient psychiatric treatment. And within a very short period of time, you go get that treatment.

Fox: I grew up in the field 20 years ago, and we would see people in the emergency room, but we’d also see people out in the street, at a business, at people’s homes, etc. And frankly, as a clinician, myself, I always prefer to see someone in their home than in an emergency room. From a clinical perspective, you get a much better perception of what’s going on for a particular individual who may be in crisis, if you’re also able to see kind of, their living environment and it gives you a better sense as to who they are, what their struggles may be, all those kind of things as opposed to meeting with someone in a, for lack of better term, a sterile emergency room environment.

That being said, if someone does need to go into the hospital, there is that need and that’s been determined, then, you know, coming into the emergency room is is not the worst thing in the world. But ideally, you have someone who comes into the emergency room, and then moves from that into an inpatient psychiatric unit as quickly as possible.

Faher: The problem is that after seeking that initial treatment or assessment, a lot of these folks have nowhere to go. And the hospitals can’t let them go, but have nowhere to put them. And so you end up with this situation, this pressure cooker situation where someone is increasingly upset and agitated and dealing with a mental health crisis, and they are literally stuck in a place that can’t treat them.

So why is that? Why is there nowhere to put these people?

Faher: Well, I mean, I guess the easy answer is we don’t have enough inpatient beds in Vermont. Everybody goes back to Tropical Storm Irene in 2011, and it forced the closure of the Vermont State Hospital. But as I understand it, we’ve rebuilt I think most or all of that inpatient treatment capacity since then, in various ways and various sites. The most recent estimate is that we need another 29 to 35 inpatient mental health beds to meet the demand that we have now, and the demand that we expect to have in the next five or 10 years. And that’s not cheap. You’re talking millions and millions of dollars, and a pretty long time frame.

You said that’s the easy answer. What’s the complicated answer?

Faher: Well, I think the complicated answer from the perspective of mental health professionals is that we don’t just need inpatient beds, maybe we need more services in the community to help people before they get to that crisis point. Our designated agencies, which are the agencies around the state that help mental health patients, are sort of overworked and underpaid, so that’s another capacity problem.

I’ve heard people talk about needing more crisis beds, beds where someone can get help when they’re in a crisis again, before the before it rises to the level of needing inpatient care. And then once you have somebody in inpatient care, one of the reasons we don’t have enough beds is there’s often no place for those folks to go when they might be ready to leave, sort of an acute inpatient environment, but they’re not ready to go home, either. They need sort of an interim step.

We have some of that, we don’t have enough of it. So there are problems really throughout the system. But all of those problems require time and money.

Fox: Some states have done things where they have entire emergency departments that are separate from their ER that’s just a psychiatric emergency department. So all the staff there are trained to work with folks having psychiatric crisis. And there’s a lot of different things, but, you know, we also have to look at how does that mesh with — Vermont statutes and laws are different than other states. And so what one state can do would require legislative changes here. So, those kind of things that we have to, you know, continue to explore, but I think the reality is, we’ve done a lot of exploring and my hope is that soon we’re able to do more than just explore and actually start — continue doing more of the development.

You said that a lot of these issues have kind of been known in some form since Irene, I wonder why some of these types of things haven’t been implemented by now? I mean, that was six years ago, I guess?

Fox: Yep. Well, yeah, like I said, there are a lot of things have been implemented, with, you know, some of the changes in emergency departments, the, you know, contracting, of having embedded staff in emergency rooms, those kind of things, but I think we, we just need to do more. I think, you know, we can’t be complacent because you know, when it’s your mother, brother, sister, father, you know, that’s sitting waiting for days on end, it’s intolerable.

Faher: One challenge with implementing solutions is that it requires navigating complex public/private partnerships. Both the hospitals and the state are pressing each other to do more.

At the individual hospital level, we are seeing hospitals make investments in their staff, some of them are hiring part time or full time psychiatrists, they’re hiring mental health clinicians to be sort of embedded in their ERs. They are building special rooms in their ERs or elsewhere to maybe create a safer place for mental health patients to be while they’re there.

But, you know, two things about those type of investments: they’re expensive, especially for a small hospital, and they’re also sort of haphazard, you know, there’s no comprehensive approach here, statewide. It’s each hospital for itself, essentially. But I think the hospitals recognize that they can’t just stand pat and let this continue to happen.

Fox: Everything that I’m about at this point really is all about access and parity. How do people access the services they need, the levels of care that they need and to make sure that we have the best ability at providing parity in access to care.

From a parity issue, I find it intriguing that when there’s an uptick in cardiac cases, what happens? Hospitals do not say, “Hey, Vermont, Department of Health, what are you going to do about this uptick in cardiac cases?” We need to have a new cardiac unit. Hospitals will start a capital campaign. They will raise money and they will open up a new cardiac unit with a ribbon cutting session. But when there’s an uptick in psychiatric people presenting to emergency rooms, the response is, “Hey, Department of Mental Health, what are you doing to resolve this?” And so I think it needs to be a partnership. Just like in the medical world, it’s not VDH that’s going to solve and help, you know, fund a new cardiac unit at a hospital, but it should be a partnership.

I wonder why. Why do you think that is that people treat mental health cases in a different way than they treat cardiac cases or anything else like that?

Fox: I think it comes from unrecognized biases and stigma. I think people you know, have an unrecognized bias. Because I struggle to come up with another answer to that, unless it’s, it’s there’s some form of bias.

The bias in that they see mental health patients as somehow more more needy? Like what kind of bias is that?

Fox: I mean, it’s, you get a lot when I meet with folks, I hear, “well your patients are in.”

You know, that kind of thing. It’s like, well they’re all, they’re our patients, they’re yours too, they’re in your emergency department. They may be under my care and custody, but they’re also under your care when they’re in your hospital, and so we have to work on this together. It’s a joint effort, the hospitals, the department, the designated agencies, private practitioners, we all have to work together to resolve this.

I asked Phoebe for her ideas.

What do you believe good care would look like to you? You know what, what would be your ideal type of facility and type of treatment?

Wagner: There wouldn’t be facilities. There wouldn’t be facilities.

She told me she found quality care at Alyssum, which is a diversion program in Rochester, Vermont, funded by the Department of Mental Health.

Wagner: Alyssum is not a facility, Alyssum is a house that has guests, and that’s what they call the quote unquote patients that are sent there come there voluntarily, because you have to be voluntary. Alyssum has wonderful people running it. At one point I’d seriously damaged my face with cigars, as you can probably see, and the staff member who was on did not call the police or call the ambulance or call anybody. She simply laid down in the bed with me and held me. Not held me down like they would in a hospital. She held me just like a mother would her child or something, even though I was 30 years older than she was.

The point is that they don’t overreact there, and they don’t punish you for things that have happened. You know, at the hospital, if I did that, they would restrain me for days.

Faher: You know, for her, and I’m sure it’s different for everyone, she found a place in Vermont that sort of was not really a medical setting. It was more about peer support. They speak to you in a non-medical non-diagnostic way, and she found that to be an environment where she could find some — this is my word, it may not be her word, but find some peace, and find some well being. Whether that’s the answer for a large portion of the population, it’d be hard to say. I do think just from hearing these stories and hearing her story, it may not be such a bad thing if we would find a way to invest in that sort of place. If it helped her, it might help others, and it’s certainly out of the box-type thinking beyond “let’s add more psychiatrists and let’s build more beds.”

You said that at a certain point over the past couple years, you haven’t had those voices and those hallucinations as much. What do you think made those things go away? What do you think has helped?

Wagner: A therapist with absolutely unconditional acceptance of me, so that she believes in a way that I had trouble believing, that there was goodness in me, that there is goodness. I mean, she would say “you’re a good person,” but I have a hard time repeating that, because I’m afraid that I’m afflicted with evil. But her totally unconditional acceptance of me without diagnoses, without labels, without anything, but just, I have to say it, love, has been immensely healing.

Mike, you’ve done this series this week, you’re our healthcare reporter. What aspects of this are you going to kind of keep an eye on going forward?

Faher: Well, I think in the short term, I’d be interested to see what the Legislature does, if anything. I don’t have a lot of clear ideas about that. But one of the folks I talked to is an advocate and a legislator, Anne Donahue. And she said that she wants lawmakers to take a really close look at this. Not just in an anecdotal or “send us a report” kind of way. What shape that’ll take, I guess we’ll know better early next year. So that’s one thing I’m looking for.

It’s hard though, because I wanted to include more information about potential solutions in my story. And I just don’t feel like there’s a lot of that out there, other than let’s build more beds, or let’s try to train people better. It’s certainly not a hopeless situation, but I’ll be really interested to see what people can come up with, because it seems clear to me that we can’t keep going the way we’re going.

Thanks, Mike.

Faher: Thanks.

Subscribe to The Deeper Dig on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Spotify or anywhere you listen to podcasts. Music by Lee Rosevere and Chad Crouch.

[/showhide]

Listen to the full poem by Phoebe Sparrow Wagner, “Poem in Which I Speak Frankly”: