Across the country, thousands of women have been running for public office this primary season, in what pundits have dubbed a “pink wave,” largely in response to President Donald Trump and the #MeToo movement.

Vermont, in contrast, has only seen modest gains in the number of women candidates since the election cycle two years ago, and the percent of women running for all public offices this year is 32 percent, the same figure as in 2016.

Two years after Trump’s election, there are more than 500 women running for seats in the U.S. House or Senate, and 62 women candidates for governor, nearly doubling the 24-year-old record of 35 women in 1994. A new record could be set if more than 10 women win.

Vermont has two women running for governor and one each for the U.S. House and Senate. However, the only one given even the slightest chance of winning is Democratic gubernatorial candidate Christine Hallquist, who would also be the country’s first transgender governor.

At the more local level, it also looks as if women across the country are getting more involved, and getting more support from the major parties.

In 2016, there were 2,648 women who won their primaries for state legislature, according to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University. With only 32 states having held their primaries, that figure is already at 2,211 this year.

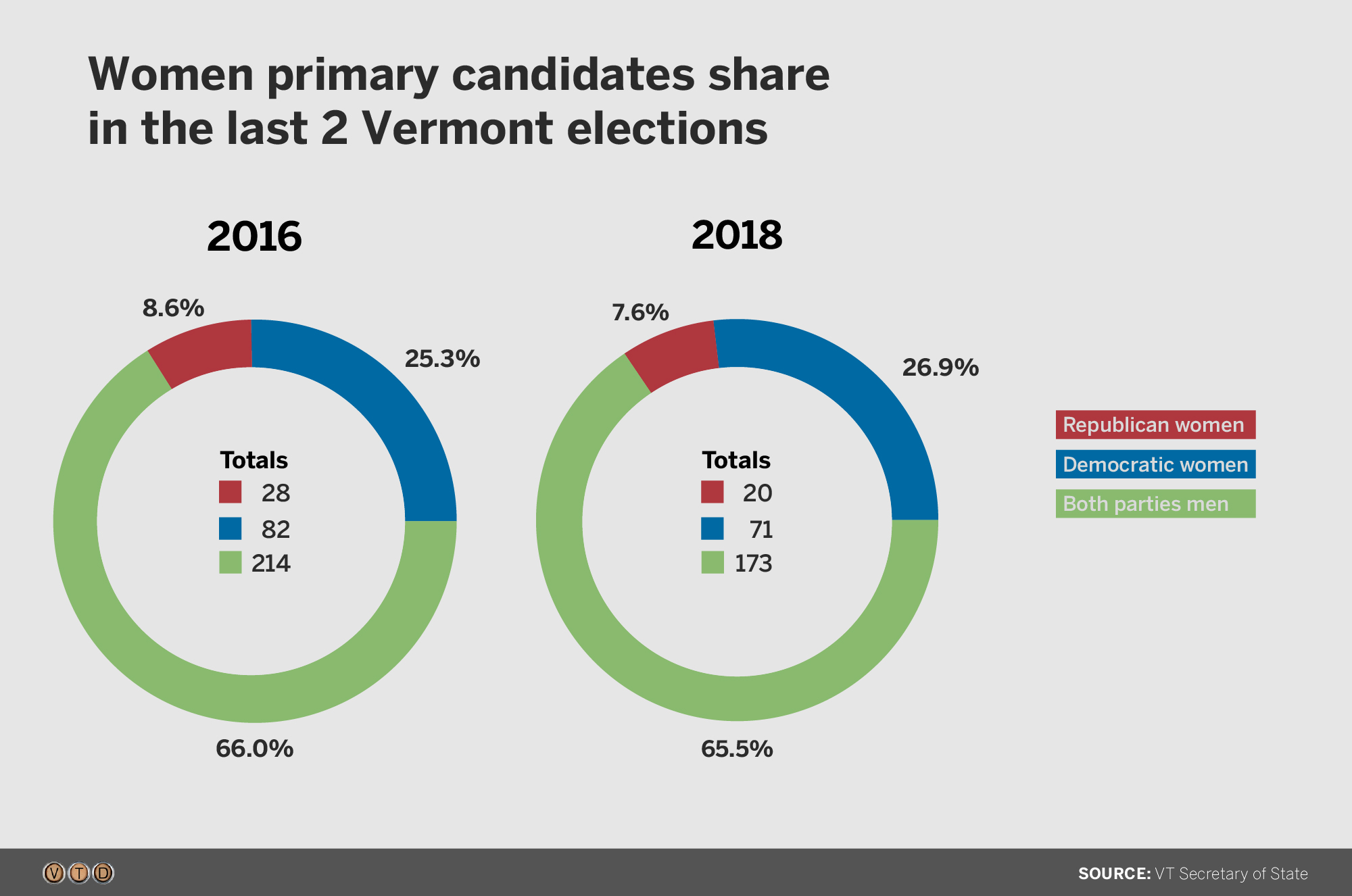

However, the tide is rising more slowly in Vermont, where it arguably already was high. In 2016, there were 110 women candidates competing in primaries for state House and Senate seats. This year, there were only 91 woman entered in those races.

Looking at the total numbers from the 2016 primary compared to this year’s, there is a slight uptick in women running for public office throughout the state — 118 in 2016 to 126 in 2018 — but there are also more candidates running this year than in 2016, so the percentage of women candidates running has remained consistent since 2016 at 32 percent.

But those seeking to increase women representation in politics say that part of the reason for incremental change this year is because how far ahead Vermont already was.

Vermont is ranked first in the country for women represented in the General Assembly with 40 percent, and the state has been either first or second in the country in this statistic since 2007 — never dropping below 37 percent.

“In Vermont we have a stronger tradition of women being in our state legislature,” said Ruth Hardy, the executive director of Emerge Vermont, an organization that recruits and trains Democratic women candidates for public office.

“We have a strong history of that and it dates back to Madeleine Kunin in the 1990s, and that saw a ripple effect where you saw women run,” Hardy said of Vermont’s first and only female governor. “So we have a smaller hill to climb and maybe less urgency.”

The tradition of women legislators is significantly stronger in the Democratic Party than in the Republican — a trend that extends across the country.

Nationally, 70 percent of the women candidates running for public office are Democrats, up 5 percent from 2016. In Vermont, 76 percent of women candidates are Democrats, which is essentially unchanged from 2016.

In the state House and Senate races this year, 71 candidates are Democrats, compared to 20 Republicans (no Republican women are running for Senate). The split in 2016 was 82 Democrats and 28 Republicans.

“The wave is actually a pink and blue wave,” said Hardy, who is a Democrat running for Senate in Addison County. “Most of the women running this year are Democrats and the Republicans did not do a good enough job of recruiting female candidates.”

In explaining this divergence between the major parties, experts are also saying that it is the Republican Party itself, and the increasingly conservative ideology it has embraced, that is keeping women from running under the party banner.

Conservative women in Vermont politics often find it difficult for their message to take hold in a state where moderate conservatism still rules the day.

“The way Republicans resonate to voters seems, in my view, to need significant improvement on the national level,” said Rep. Heidi Scheuermann, R-Stowe, who has served in the General Assembly since 2007. “But in Vermont, it’s a very different demographic here than nationally. So the more moderate conservative message resonates with Vermont voters.”

Rep. Anne Donahue, R-Northfield, who has held a seat as a state representative since 2003, said that Democrats have become the party where “women’s issues” are welcome and that has attracted more women candidates, but Donahue says this limits the discussion of what are and what aren’t “women’s issues.”

“I think Republicans have a lot of interest in business growth and the economy,” Donahue said. “So I guess you could speculate and say women are more interested in support for families, but I think that’s really demeaning to both genders.”

Scheuermann says that in Vermont, its not necessarily about women running for public office, but about Democratic women running for office.

“I think what you see with Emerge, which is great, but too often it’s referred to in the press to promote women in politics. It’s to promote Democratic women in politics,” Scheuermann said.

“I don’t think Emerge would come out in support of me if I was running against a Democratic man,” she said.

But there is no Emerge-equivalent for conservative women and that remains part of the problem facing the Republican Party if it wants to attract more female candidates.

When it comes to Vermont’s highest political offices, Madeleine Kunin is a singular figure.

If Democrats Hallquist or Brenda Siegel were to beat incumbent Gov. Phil Scott, they would become Vermont’s second woman governor after Kunin, who served from 1985 to 1991. But few are expecting that to happen, considering Vermont’s history of giving governors a second term and the strength of the candidates Scott is facing.

“We do have a whole group of women who could run for governor, but who still think that it would be futile,” said Kunin. “Scott is still a strong incumbent, and the fact that Vermont tends to re-elect a one-term governor; women who have built their resumes have been more cautious and careful, but they will be strong candidates in the future.”

Vermont is also all but certain to maintain its distinction of being the only state that has never sent a woman representative to Congress. That distinction was shared with Mississippi until the governor recently appointed the state’s agriculture commissioner, Cindy Hyde-Smith, to a vacant Senate seat.

The last two races for the Vermont’s congressional delegation seats has seen a dearth of legitimate women challengers. In 2016, it was again Cris Ericson, a perennial candidate, running against Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vt.

This year, Folasade Adeluola is challenging Sen. Bernie Sanders in the Democratic primary and Republican Anya Tynio has filed to take on Rep. Peter Welch, D-Vt.. Neither is well-known or given any serious chance of winning.

Hardy said there were no prominent women competing for spots within the congressional delegation because the three men are just too popular throughout the state.

“In Vermont we love our incumbents and we have very strong progressive members of our congressional delegation who all happen to be older white men,” Hardy said. “And clearly they aren’t going to be around forever, and when one chooses not to run we will see a lot of women in the pipeline ready to run for those seats.

For Kunin, who has been pushing for more women to run since she was first elected to office in 1971, this national surge in women running is an opportunity — win or lose and regardless of party affiliation — to change the country’s political structure.

“Many women will not get elected, but the very fact that they have put their hat in the ring changes the whole dynamic,” she said. “And some will get elected, and more incumbents will be getting challenged that were never challenged before and they will have a wake-up call.”