Editor’s note: Mark Bushnell is a Vermont journalist and historian. He is the author of “Hidden History of Vermont” and “It Happened in Vermont.”

[T]he government braced for a military attack that seemed imminent. Congress, fearing any unrest would weaken the country, made it a crime even to criticize the president or the federal government. Critics bridled at this curbing of civil liberties. Things were tough in 1798.

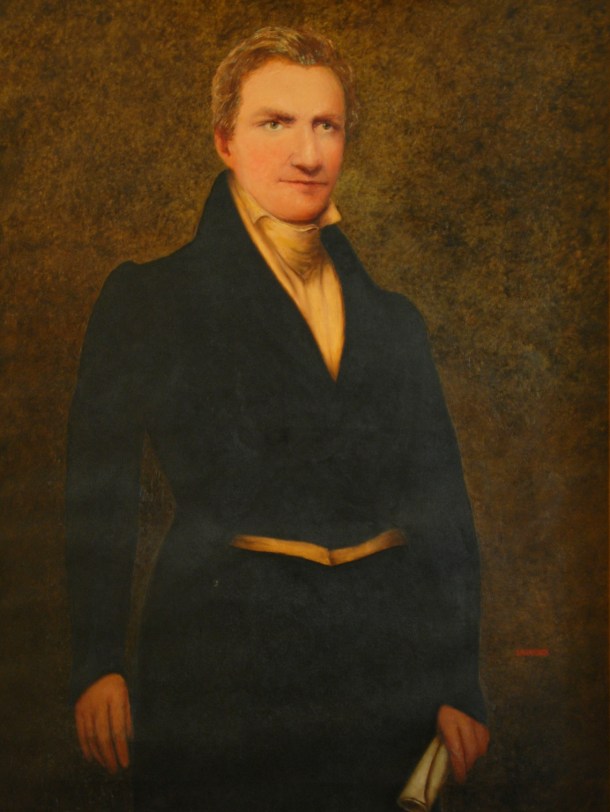

A Vermonter found himself in the midst of this turmoil. For four months, Vermont Congressman Matthew Lyon sat in a Vergennes prison cell for the high crime of implying that President John Adams was pompous.

If anyone had been taking bets on who would get snared when Congress passed the Sedition Law that year, the heavy money would have been on Lyon. He had a way of speaking his mind, and paying for it.

A native Irishman, Lyon had run away from home at the age of 15 and hopped a ship for America. Short on funds, he became the captain’s indentured servant. Upon arriving in the colonies, the captain sold his servitude to the wealthiest merchant in Connecticut. But Lyon’s new master found his servant quarrelsome. The master was a Tory – his sympathies lay with the British. Lyon was an ardent Whig, an advocate for liberty, and wasn’t shy about telling his master so. When the merchant tired of Lyon, he traded his services to Hugh Hannah of Litchfield, Connecticut, in exchange for a pair of bulls. (Ever after, Lyon’s favorite exclamation was “By the bulls that redeemed me …”)

It proved a fateful swap. Litchfield happened to be the birthplace of a man named Ethan Allen. The men became friends. Lyon eventually married Allen’s niece and may have worked at his ironworks.

Soon after Lyon’s arrival, Allen decided to go into land speculation and ventured north into the New Hampshire Grants (which would become Vermont). Lyon, his indenture complete, moved with Allen, as did neighbors Thomas Chittenden, Remember Baker and other hardy men who would later dub themselves the Green Mountain Boys.

Lyon’s first brush with infamy came in 1776 during the Revolution, when he was part of a group of Continental Army soldiers who mutinied. Stationed in Jericho, the men were far ahead of the main army and short on supplies. The men feared they were vulnerable to an Indian attack, so they retreated. Lyon, by then a lieutenant and a veteran of the previous year’s victory at Fort Ticonderoga, later claimed that he opposed the withdrawal. But he was given the unpleasant task of reporting the maneuver to Gen. Horatio Gates. The general wasn’t pleased. He had Lyon court-martialed, fined and thrown out of the army, though he continued to serve as a civilian.

Never one to take a hint, Lyon ran in 1779 for Vermont’s first Legislature as a candidate from Arlington, and won. The new governor was his old friend Thomas Chittenden, whose daughter Lyon would soon wed after his first wife died.

While Lyon had friends in high places, he had powerful enemies, too. In 1785, he was impeached by the Legislature for refusing to release records regarding the confiscation of property from British sympathizers. Some suspected he profited from the seizures. He was convicted and fined 500 pounds.

But again, adversity was no match for Lyon. Having helped found Fair Haven, he was elected to represent that town in 1787.

As a politician, Lyon was what we would be called a populist. As a man of humble origins, he criticized legislators who were lawyers, arguing that they abetted the aristocracy and that they wanted to make farmers renters rather than landowners.

“Lawyers …,” he said, “suck their principles from the very poisonous breast of monarchy itself.”

But Lyon had higher aspirations than being a state legislator. After several attempts, he won election to the U.S. Congress in 1796.

When he arrived at the capital, which was then in Philadelphia, he attacked anything that reeked of privilege. His first speech criticized the practice of congressmen waiting on the president in person to approve his policies. He called the custom “inconvenient, ridiculous, slavish, anti-republican, and a waste of time and a delay of public business.” Lyon was never one to mince words.

Neither were his rivals. As a Jeffersonian republican, Lyon quickly found himself targeted by the opposition Federalist press. In 1797, a newspaper called the Porcupine’s Gazette dubbed him “The Lyon of Vermont,” and mocked his Irish ancestry, his marriage to Chittenden’s daughter and his hard years of indentured servitude. The paper wrote that Lyon “was petted in the neighborhood of Governor Chittenden, and soon became so domesticated, that a daughter of His Excellency would stroke and play with him as a monkey … (He) has never been detected in having attacked a man, but report says he will beat women.”

As bad as things were for Lyon, they only got worse in 1798. The trouble started when he commented loudly during a break in Congress that Connecticut’s delegation served its own interests rather than its constituents. Roger Griswold, a Connecticut representative, took offense and made a jibe about Lyon’s court martial. Lyon ignored the remark, so Griswold walked across the House chamber, grabbed his arm and repeated the comment. Lyon responded by spitting in Griswold’s face.

After order was restored, Griswold’s Federalist allies moved that Lyon be removed from Congress. Fourteen days of vitriolic debate over Lyon’s fate followed. As Rep. Edward Livingston of New York described it: “Gentlemen rose to express their abhorrence of abuse in abusive terms, and their hatred of indecent acts with indecency.”

Thomas Jefferson saw it as a purely partisan move. “(T)o get rid of his vote was the most material object,” he wrote.

But there was no shaking the Lyon of Vermont. The Federalists couldn’t muster the two-thirds majority needed to oust him.

Frustrated, Griswold fought back. In late February, he coolly walked across the Congressional chamber, a newly purchased hickory cane in hand, and beat Lyon bloody. Lyon tried weakly to defend himself with a pair of fireplace tongs. This time, Congress voted on whether to expel both members, but that motion failed, too.

Which brings us to the Sedition Law that caused Lyon such grief, and then turned him into a national hero. The law, which went into effect on July 4, 1798, made it a crime for anyone to write or publish words bringing the U.S. government into “disrepute, or to stir up sedition in the country.” The law allowed for fines up to $2,000 and imprisonment of up to two years.

Lyon had written a letter to the Vermont Journal, a Federalist paper in Windsor. In it, he stated that he would support President Adams, if Adams used his power for “the promotion of the comfort, the happiness, and the accommodation of the people” but would not if he saw “every consideration of public welfare swallowed up in a continual grasp for power, in an unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, or selfish avarice.”

Lyon wrote the letter on June 20, but the newspaper did not publish it until after the law took effect. For writing the letter, and helping publish a similar one by another man, Lyon was arrested and tried in October in the U.S. Circuit Court in Rutland.

Lyon was found guilty, sentenced to four months and fined $1,000. He was dragged off to a jail cell in Vergennes, where for a time he was denied paper, pen, and heat.

Word of his treatment leaked out. The nation was appalled. To many people, Lyon became a martyr. Vermonters didn’t let a small thing like Lyon’s being a convict deter them from supporting him; they re-elected Lyon while he was still in jail.

Lyon’s long trip to Philadelphia became a sort of victory lap, with supporters turning out at towns along the route to cheer him.

Lyon found Congress little changed. He was greeted with a resolution for his expulsion, since he’d been “convicted of being a malicious and seditious person, of a depraved mind, and wicked and diabolical disposition …” Again, Lyon’s enemies failed to unseat him.

But Congress had more important business: deciding the presidential election. Jefferson and Aaron Burr had tied in the electoral vote, so it was up to the House to pick the winner. For seven straight days, neither Jefferson nor Burr could marshal the votes needed. Finally, the impasse was broken.

What a sense of victory Lyon must have felt when, in his last term representing Vermont, he could cast the state’s vote for Jefferson, helping give his ideological mentor the margin he needed.