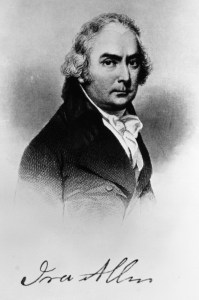

[I]ra Allen’s life ended badly. The man who gave Vermont its state university and placed it in Burlington was almost relegated to the dustbin of history. Reports of his death in January 1814 merited only a couple of lines in Burlington’s Northern Sentinel newspaper. Worse yet, trustees of the University of Vermont didn’t even bother to mention his passing at their next meeting.

If he weren’t already dead, the latter snub might have killed him.

The trustees’ disdain for, or perhaps uninterest in, Allen is understandable. Although the university might not have been founded without Allen, once founded, it survived in spite of him.

In the 1770s, Allen bought up land in the Champlain Valley and convinced family members to do likewise. He envisioned the city of Burlington taking advantage of its physical gifts – its location on Lake Champlain and access to the powerful Winooski River falls – to become a commercial giant.

By the late 1780s, his vision had expanded. Allen wanted to make Burlington the intellectual capital of Vermont, the site of the state university. But Burlington had competition.

Vermont’s 1777 constitution called for the Legislature to establish a state university, and lawmakers obliged, sort of. The Legislature made Dartmouth College in New Hampshire the unofficial state university.

And Dartmouth’s town, Dresden (now Hanover), was briefly part of Vermont in the late 1770s and early ’80s, when Vermont’s Legislature kept annexing and shedding sections of western New Hampshire.

The Legislature was so cozy with Dartmouth, in fact, that in 1785 it granted 23,000 acres in the Northeast Kingdom to the school. The town, named Wheelock after a father and son who each served as the school’s president, would provide lease money to fill school coffers. (Indeed, Dartmouth still holds some property in Wheelock, and under the terms of an agreement with Vermont dating from the 1830s, the school agreed to waive tuition for students from that town who gained admission.)

In 1786, the Legislature revised the Vermont Constitution and deleted the line about creating a state university. Some see the hand of Dartmouth President John Wheelock in the change. Omitting mention of a state university meant removing competition for Dartmouth. And having Dartmouth as a quasi-state school gave more clout to towns along the Connecticut River in their power struggle with Allen and others on the west side of the Green Mountains.

Although the constitution no longer required the Legislature to establish a state university, some Vermonters still thought it would be a good idea, particularly if it were built in their hometown. In 1785 Elijah Paine, of Williamstown, offered 2,000 pounds toward creation of a university in his town. A legislative committee rejected the offer, saying Paine’s contribution was too small.

Allen decided he would promote Burlington as the best home for a state university, and he would create an incentive package that would top Paine’s offer. Allen gathered support from prominent citizens, including Gov. Thomas Chittenden. Together they pledged 5,655 pounds to the school. Of that, Allen shouldered the heaviest burden; he promised to give 4,000 pounds and a 50-acre site if the university were built within 2 miles of Burlington Bay.

The site was far enough from Dartmouth that it wouldn’t compete for the same students, Allen argued. But it could draw students from Quebec and upstate New York, which had no colleges.

Allen, who was Colchester’s state representative, presented the idea to his fellow lawmakers in 1789. They established two committees to study the proposal but took no action that year or the next.

The 1791 session started no more promisingly. The Legislature was tied up with debate over joining the United States, but leaders promised Allen that his plan would be debated in the fall. He spent the time lobbying legislators to back his proposal.

On Oct. 24, 1791, when the Legislature finally voted on the issue, Allen and Burlington won. The city received 89 votes. Far behind were Rutland with 24 votes; central Vermont (either Montpelier, Berlin or Williamstown) with 11; and Danville and Castleton with one each.

Universitas Viridis Montis (Latin for “University of the Green Mountains”) had been founded. But that didn’t mean it was open for business. That would take nine more years of financial and legal wrangling.

With his plan accepted, Allen scrambled to come up with the money he had pledged. He established a trading company with one of his brothers, hoping to tap into the profitable Quebec market. But that scheme, like so many more that Allen would later try, failed.

If Allen was short on cash, he was not short on land. At one point he owned 200,000 acres in Vermont, but he never sold or leased any of his land to benefit the university.

But Allen tried to tap other sources. He wrote to New York officials, requesting a grant of land to help support the university, which he noted would be accepting students from that state. They weren’t persuaded by his logic.

In June 1792, the university’s trustees gathered in Burlington and chose a 50-acre parcel from among Allen’s holdings to be home to the school. The land, nothing more than a pine woods at the time, was worth 1,000 pounds, the trustees figured. But that still left Allen on the hook for 3,000 pounds.

In an amazing show of hubris, or perhaps optimism, Allen told the Legislature in 1793 that he would increase his pledge by 1,000 pounds, if they changed the name to Allen’s University.

The Legislature, apparently taking the offer seriously, took two years to reject it. The school’s 10 trustees, who by some accounts included nearly every college-educated man in the state, were forced to search for donors who would keep their promises. To be fair, Allen was not the only UVM supporter who failed to pay what he had pledged, but it was his massive pledge that had won Burlington the university.

By 1799, trustees had raised enough money to build a president’s house. The next year, President Daniel Clarke Sanders started teaching classes to a handful of students. Sanders constituted the school’s entire administration, its lone instructor and sole dorm monitor. In 1804, UVM graduated its first class, of four students.

The university’s debt totaled $20,000 (Congress having recently approved the general use of dollars), and students’ annual tuition of $12 wasn’t going to pay it off quickly.

Worse yet, UVM now had competition. The Legislature had granted Middlebury College a charter in 1800, and that school was angling to be named the state university. President Sanders bitterly criticized the upstarts, declaring that the new college “could only benefit a few individuals at Middlebury who wish to limit all public favors to that little spot of mire and clay.”

Middlebury continued to press its claim. In 1805, school officials told the Legislature that it deserved half of UVM’s lease lands. It took lawmakers five years to decide that UVM should retain its lands. The school gradually sold off that property to pay creditors.

UVM’s first students were no less impoverished than the school. Despite the low tuition – which caused President Sanders to declare: “No college on the continent can be so cheap” – students were forever crying poor. The first question UVM’s debating club pondered was “whether a person enjoys more happiness below a mediocrity of property than one above.” Following the debate, students voted 4 to 2 that the poor were happier. In those days, students arrived on campus with what they needed, including firewood and, in one case, a cow for milk.

Allen might have been even worse off than the students. In 1803, he was arrested for debt in Burlington. He made bail and quickly fled Vermont.

But his allegiance to UVM remained. He risked arrest the next year to return to Vermont to resign his trustee seat in person.

For decades after his death, UVM’s founder was rarely spoken of on campus. But in celebrating UVM’s centennial at the 1892 commencement, Latin professor John Goodrich gave an address praising Allen’s contributions to the school and calling for a day to remember him. He proposed declaring May 1 (Allen’s birthday) Founder’s Day. The administration accepted the challenge, and UVM celebrated Founder’s Day until the 1940s, when the name was changed to Honors Day.

Allen’s reputation was further rehabilitated during the 1920s. James Wilbur, a wealthy businessman smitten with the founder’s courage and leadership, donated Ira Allen Chapel and a statue of the man to UVM.

Allen was, as one historian put it, a hard founding father to love. But now all that has been forgotten.

Reflections on “ye”

In a recent column, I wrote about the travels and travails of a cranky Connecticut minister who had visited Vermont in 1789.

In his journal, the Rev. Nathan Perkins used the word “ye” where we today would write “the.” One reader said I should have transcribed “ye” as “the” in quoting the reverend, since that’s how a person in the 18th century would have read the sentence.

I take his point. I decided to leave the original spelling to give the reader a sense of how different the world was that Perkins knew — not only was the primitive Vermont he encountered unfamiliar to us today, but so too was how he wrote about it. The way he would have pronounced “ye,” however, would have been perfectly recognizable: “the.” I should have pointed that out.

The reader’s comment sparked me to take a dive into linguistics to understand how we got from “ye” to “the.” It’s an example of how languages evolve. “Ye” was originally written starting with a letter called thorn, which was part of the Old English runic alphabet, which adopted it from the Norse alphabet. Thorn is still used in Icelandic. The letter, which signals a “th” sound, looked rather like a “y” when written in script — so much so that some printers began using “y” in its place.

Over time, the spelling “the” replaced “ye,” which also eliminated confusion with the word “ye,” as in “hear ye, hear ye,” which derives from Old English and can be used as an honorific to address a respected individual, or as a plural for “you.” Of course, hardly anyone says “ye” anymore, except in Shakespeare productions and Christmas carols, and in a few English dialects. Which is a pity really. We could use an easy way to address a group of people. Something more formal and gender neutral than “you guys.” Of course, Southerners don’t have this problem. In these situations, they can just say “y’all.”